- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

Testimonies Page 9

Testimonies Read online

Page 9

Here the local landowner lived in a house out of reach when he visited Wales (which was seldom), and his agent lived at the far end of the estate, ten miles beyond the Plâs. The parson was what might be termed a career-clergyman. He was a collier from the south who had shown a good deal of scholastic promise in his boyhood: this had opened many possibilities to him, and casting about for a life that would assure him security, ease and prestige he had fastened upon the Church. I do not know how livings are arranged in the Church in Wales, but however it was, he had appeared in this parish some twenty years before, and by all accounts (I am repeating vulgar, ill-natured gossip) he had instantly given up all further ambition. When he came there had been a congregation sufficiently numerous to fill the old church on great days. Now two old ladies resentfully listened to him mumbling through the obligatory duty, and the nonconformist chapels were fuller than they had ever been.

I went down at Christmas and Easter and sat among the dust and the droppings of the bats. Each time I came away angry and sorry for the old church—it was built in the fourteenth century, and it had one or two fine tombs.

I am afraid he took a malicious pleasure in his nastiness; but he was immovable, so long as he committed no ecclesiastical offense, and he never did that. He led a strange torpid life in the week, doing nothing in the kitchen of the rectory, in a state of great sordidness. The gardens had been left to grow wild, except for a little square of potatoes half-buried in the wilderness: tall grass had invaded all but the very middle of the gravel drive, and once as I passed I saw a pale, lean sow between the noble magnolias that had survived and the lovely petals were dropping slowly on her back.

I talked to him once or twice. With all my respect for his cloth, I found it difficult to be civil: he had a fawning, obsequious manner that I suppose he had picked up on the principles of Heep in his younger days, but now it was mixed with an intolerable confidence. In the first two minutes he asked half a dozen impertinent questions, and all the time he kept touching either my elbow or my shoulder.

However, by this time I had been a long while without seeing anybody but the people in our valley. It was during a very painful time—I had not grown hardened to it at all—and more than ever I was thrown in upon myself. So I was not altogether sorry to see a man coming up my path one morning between showers. I knew him by sight, having passed him often enough in the lower village and in Llanfair: he was a Mr. Skinner, who lived at Tan yr Onnen—a bachelor.

He came rather furtively up the path, with his hand in the pocket of his coat; he was frowning, and I had the instant impression that he would be very glad to find his knock unanswered so that he could push his note through the letter box and go away.

I gave him a glass of muscat. He was ferociously shy and would do nothing to help the small-talk along. He seemed to dislike me and I wondered why he had come: when he got up to go he said that he hoped I would take tea with him on Thursday. I said that I should be very happy, but when I had closed the garden gate behind him I thought that I should probably send a civil excuse: it was a long way and we appeared to have nothing to say to one another.

By Wednesday I had done nothing about it, so on Thursday I put on a clean shirt and walked down the valley to the main Llanfair road, and along it to the lane that led to Tan yr Onnen. Skinner’s house was a dark, severe building: it had been built about eighty years ago, and the whole of its outside was covered with big overlapping purple slates. It was comfortable enough inside, though, and the room in which Skinner received me had a good fire, a Turkey carpet and shining brass fire-irons. There were comfortable chairs and the walls were lined with books. Skinner was much more at his ease in his own house than in mine, and he put himself out to be a good host. We talked about the neighborhood, the weather, and somehow we got onto chess: he asked me if I played. I did, a little, I said—in point of fact I rather piqued myself on my game. Bridge and chess; those and domestic comfort were the only things that I missed. Bridge to a less degree, because it is so rarely possible, even in the best conditions, to gather four civil players of equal skill at one time, and bridge under any other conditions is a torment. He proposed a game after tea, and I was very glad that I had said I was out of practice, as well as being an indifferent player, because he beat me twice running with humiliating ease.

When I went home, much later than I had expected on setting out, I was pleased with my afternoon and I looked forward to seeing Skinner again.

He was a difficult man to know well. We had exchanged several visits before I knew anything about him at all. He was very reserved, and in this case I could not gather information about him by asking my neighbors. They knew that we were acquainted, but they offered no remarks. I do not know that I liked him very much. He was so hedged in by his shyness and a long habit of withdrawal that we remained at a distance for a long time. He was remarkably ugly, too, and it is difficult to overcome a prejudice against ugliness. When we did grow more confidential I did not care much more for him: he was intelligent in a way—thought for himself—but there was something hard, sterile and selfish down there, and it appeared to me that he did not have nearly enough ballast of solid information for his solitary thinking to be of any value. With all his diffidence he had a pretty high conceit of his intellectual abilities: I do not think that he had often mixed with men better informed than himself.

His superiority in chess supported his opinion, and I must say that he played a good game. I tried very hard indeed to beat him and occasionally I succeeded, but he was really outside my class. He had a wide theoretical knowledge (which I lacked) so he had to work much less with his head than I did; the result was that my concentration would fail toward the end, while he was still thinking as clearly as at the beginning; I would make some foolish error and it would all be over—I could never afford to make a slip with him. He favored a very closed queen’s pawn opening and an involved, complex middle game. This had something in common with his character; but while his thinking worked out well in chess, where the logical connection is predetermined, in more important things it did not.

However, he enabled me to pass many hours that would have been hard to bear otherwise. We nearly always played chess, but sometimes it would happen that I was out of form (a heart wrenched sideways, that was the real trouble) and I could hardly give him a game; when it was like that and I had been beaten three times in a row, we would sit and talk.

Skinner had been a magistrate until a few years before: I gathered that he had retired, or had been asked to retire, because he declined to administer some law or regulation that he considered unjust. He did not go into it, supposing me, I think, to be au courant, but I believe he had made some very strong remarks from the bench. I could well imagine it; he had a fund of nervous violence that almost got the better of him at times, when we spoke of some controversial subject. His time as a justice of the peace had given him a particular insight into the life of the people, and he had many interesting things to say about them. It had also distorted his view. I was surprised to see how little allowance he made for this distortion: he saw the local inhabitants as a bitterly litigious quarrelsome, perjured crew, drunkards, bloody and revengeful. He also attached much too much importance to those crimes like incest and bestiality and to bastardy cases—they are common enough, but they do not appear in the papers, and they had taken him by surprise and shocked him very much. He had led a curiously pure life; he was a natural bachelor, and perhaps there was some abnormality there.

I suppose he liked Wales. He lived there voluntarily: there was nothing to detain him if he did not like the country. Yet I cannot call to mind any occasion on which he said anything pleasant about the inhabitants: dozens of his stories occur to me; they all showed the Welsh in a bad light.

One of the things that he held against them as a particular national vice was their admiration for Englishmen. “There is this stupid provincial chauvinism on the one hand,” he said, “with all the fandango about the language and

nationalism and so on, and on the other hand a servile imitation of Liverpool manners. Once they get on a bit, what language do they talk? English every time, unless they want to make political capital out of Welsh. When there was an English regiment stationed here alongside a Welsh one, who did the girls go with? The Englishmen, always. Where’s the Welsh gentry? It is either extinct or anglicized. Anyhow, the mob does not look up to it—the spirit is too mean for respect—the summit of their social ambition is to be a doctor, a minister, a chemist or a teacher. It is a society where the lower middle class is the top, like in America. There’s nothing generous or open about it.

“The values they respect are false; good manners and social distinction must be imported to be any use. Where can a mediocre, rather vulgar Englishman settle and become a local bigwig simply because of his nationality? Only in Wales.

“No, no; there is no real national pride: nothing deep and steady, no self-respect, only hysterical play-acting. They affect to despise England and the English, but they prostitute their country to char-à-bancs full of the scum of Lancashire and Stafford, and when an Englishman of some means settles among them, they lick his boots.”

I ventured to question a great deal of what he said, but he had grown excited—he was walking up and down, biting his nails, and I saw, that apart from registering my disagreement, there was nothing I could usefully say.

“Oh, I know very well that you do not see it as I do,” he said, “but believe me, I have been here a good many years, and I started out thinking as you do. I found them very sympathetic: I found their respect very flattering, and being half Welsh on my mother’s side I thought I was more or less one of them. I began learning their language, and I deluded myself that I would thoroughly understand them and identify myself with them in a year or two. But the more you know about them the less you like them, and anyhow you never come to the point where you think as they do. You may suppose them to be open, simple people—the mountain farmers, at any rate. But they are not. They just make a fool of you. They are a closed race, and you never arrive at understanding the motives that lie behind their actions. You see the results, and you condemn them; but you cannot see farther than that. It was, in fact, one of the farms near your place that gave me my first insight into their character—one of the nicest farms you can imagine.”

I asked him whether in this day and age it was really worth talking about national character: I was trying to turn the conversation, because I did not like him when he talked in this enthusiastic, overwrought way.

“No, not in most cases; but in the case of the Welsh, yes; certainly. You must have noticed how strongly their national types are marked. There is the little dark lard-faced kind you see in draper’s shops and dairies all over England and in the Welsh towns. Then there is the bony-faced sort with high cheekbones and widely separated eyes and a nose with hardly any bridge—gray eyes, usually, and medium height. And then there is the tall sandy-haired lean type—the ancient Britons, as I call them: they are exactly what that Roman (Suetonius or Agricola, which is it?) described, and they have stayed the same. Take the children in the village, there is never any doubt for a moment who they belong to; they all look exactly like their fathers or their mothers. They always breed true. You can cross them how you like, but the children always come out little Welshmen, with the same mental reactions—you may shake your head, Pugh, but it is the case [I was thinking, in point of fact, of himself as a living contradiction of what he said] and you will come round to my way of thinking if you stay here long enough. No, the blood is as strong as Jewish blood, and the Welsh parent is always the dominant partner from the genetic point of view. [What the devil have you or I to do with genetics? I thought. It is an exact science.] That is why I feel justified in talking of a national character. But I will tell you about these people at the farm.

“I do not think I would be breaking any rules if I were to tell it with names and places—it was nearly all out in public at the end—but perhaps I ought to change the names and ask you not to repeat the details.

“These two brothers, and the wife of the elder, farmed … well, Tŷ Bach. The younger was a widower, childless, like the others: he was a more retiring, timid man than his brother, and something of a bard. It was an ideal ménage. They were not well off, but they were comfortable; that corner of land is fertile, and although it is small it kept the three of them even in bad years. They had an excellent understanding among themselves and they worked together like characters in a moral story-book. I speak of what I know, because the younger one gave me Welsh lessons, and I saw them at all times. They would not have been anything like so comfortable with children—apart from the expense the house was very small. It was a long house: there are still a few of them inhabited, you know—those long low old houses with the people on one side of the passage and the cattle on the other, with one big kitchen and a half-loft over it and hardly anything else. The dairy was part of the main room—an alcove behind the chimney-breast—and hens were walking in and out all the time. It was the kind of room where a wireless set looks mad, like something out of another world. I don’t know how people ever manage to bring up children in those places, but they do: I knew a family of thirteen in one.

“However, there were no children in this case. A little farther down there was a widow with five or six. She was said to be a widow, but I don’t know that anybody had ever married her. She was one of those curious things, a rural whore—well, perhaps not whore, because I doubt if she was ever paid, but the children all had different fathers. She was a hideous slattern, mentally deficient I think, and apparently quite old, but still year after year she produced these children.

“I must say this for the people up there, that although they would not have anything much to do with the woman they were kind to the children. They went to the village school with the others, the schoolmaster saw to it that there was no difference made, and there were people who gave them proper clothes and taught them cleanliness and took them into their homes.

“The people I am talking about, the Evanses, had a particular fancy for the second boy, who was called Alfred—his father was probably an English vagrant. Alfred was always at Tŷ Bach, a well-mannered little chap for a Welsh boy—not that that is saying much, because they are the most indulged, spoilt set of brats I have ever come across—and he helped with all the things that a boy can do. I used to see him eating enormous meals there at all hours of the day, and it was some time before I understood that he was not of the household.

“Well, as I was saying, these people pretty well made themselves the foster-parents of this lad. I could bring dozens of instances as evidence of mutual affection, encouragement, and so on and so forth. But the point is that the boy was thoroughly liked by the childless, middleaged people of Tŷ Bach.

“Very well. In the winter the brothers were cutting chaff. You have seen the big external water wheels in most of the farms? This one still worked; they had a good stream, and the wheel churned the milk, cut the chaff and turned a grindstone.

“You cut chaff by feeding straw into the machine at one side: toothed rollers carry it in and a large, heavy wheel with curved blades attached to its spokes cuts it into short lengths. The wheel revolves very rapidly and makes a deafening noise when it is cutting.

“The younger brother was shoveling chaff into the storage place; the elder was in the straw-loft. The boy was feeding straw into the machine: he had been told not to touch it.

“The elder brother heard Alfred scream, but before he could get down from the straw the mischief was done: the younger brother, on the other side of the machine, did not hear the scream but did hear the changed note of the cutter and ran to stop it. He kicked the driving-belt off and between them they got the boy’s arm out. The hand was gone just below the wrist and the forearm was terribly mangled: he was bleeding profusely and he was unconscious.

“There was one thing clear in the subsequent confusion: a case for damages could be brought

against them. They had not expressly invited the boy; they had even told him not to touch the machine, the guard of which was defective; but the case might lie.

“They carried the boy through the blinding rain to a shaft some three hundred yards from their house. It was an unsuccessful trial shaft for a slate quarry and they used to throw their dead sheep down it instead of burying them in the shallow earth. The boy was certainly unconscious, but whether he was dead or alive when they threw him down was never established. They threw rocks and earth on top of him.

“Very well. There were inquiries made, but they came to nothing and it was supposed that Alfred, who was a forward, adventuring lad of thirteen, had gone off on a lorry to seek his fortune perhaps at sea. He was big for his age, precociously self-reliant, and he was determined to be a sailor in time. There were plenty of long-distance lorries passing on the main road, and once before Alfred had gone as far as Swansea before being discovered.

“In seven years the brothers fell out. The woman was now about forty or forty-five; her personality appeared to change radically and she no longer made the house comfortable for them. She would no longer cook: their meals came out of tins or they cooked them themselves. The atmosphere of the house was poisoned by her nagging.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

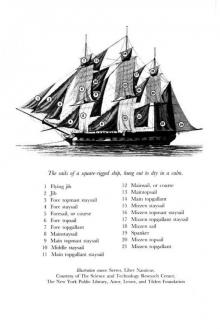

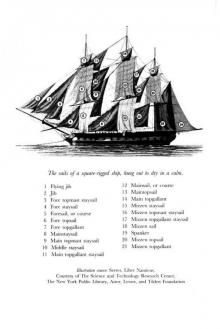

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea