- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Commodore

The Commodore Read online

THE COMMODORE

Patrick O'Brian is the author of the acclaimed Aubrey-Maturin tales and the biographer of Joseph Banks and Picasso. His first novel, Testimonies, and his Collected Short Stories have recently been reprinted by HarperCollins. He translated many works from French into English, among the novels and memoirs of Simone de Beauvoir and the first volume of Jean Lacouture's biography of Charles de Gaulle. In 1995 he was the first recipient of the Heywood Hill Prize for a lifetime's contribution to literature. In the same year he was awarded the CBE. In 1997 he was awarded an honurary doctorate of letters by Trinity College, Dublin. He died in January 2000 at the age of 85.

The Works of Patrick O'Brian

The Aubrey/Maturin Novels

in order of publication

MASTER AND COMMANDER

POST CAPTAIN

HMS SURPRISE

THE MAURITIUS COMMAND

DESOLATION ISLAND

THE FORTUNE OF WAR

THE SURGEON'S MATE

THE IONIAN MISSION

TREASON'S HARBOUR

THE FAR SIDE OF THE WORLD

THE REVERSE OF THE MEDAL

THE LETTER OF MARQUE

THE THIRTEEN-GUN SALUTE

THE NUTMEG OF CONSOLATION

CLARISSA OAKES

THE WINE-DARK SEA

THE COMMODORE

THE YELLOW ADMIRAL

THE HUNDRED DAYS

BLUE AT THE MIZZEN

Novels

TESTIMONIES

THE CATALANS

THE GOLDEN OCEAN

THE UNKNOWN SHORE

RICHARD TEMPLE

CAESAR

HUSSEIN

Tales

THE LAST POOL

THE WALKER

LYING IN THE SUN

THE CHIAN WINE

COLLECTED SHORT STORIES

Biography

PICASSO

JOSEPH BANKS

Anthology

A BOOK OF VOYAGES

HarperCollinsPublishers

77-85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.HarperCollins.co.uk

This paperback edition 2003

Previously published in B-format paperback

by HarperCollins 1997

Reprinted seven times

Also published in paperback by Fontana 1995

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1994

Copyright © The estate of the late Patrick O'Brian CBE 1994

Patrick O'Brian asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

ISBN 978-0-00-649932-9

Set in Imprint by

Rowland Phototypesetting Ltd.

Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St. Ives plc

All rights reserved. no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

FOR MARY, WITH LOVE

Chapter One

Thick weather in the chops of the Channel and a dirty night, with the strong north-east wind bringing rain from the low sky and racing cloud: Ushant somewhere away on the starboard bow, the Scillies to larboard, but never a light, never a star to be seen; and no observation for the last four days.

The two homeward-bound ships, Jack Aubrey's Surprise, an elderly twenty-eight-gun frigate sold out of the service some years ago but now, as His Majesty's hired vessel Surprise, completing a long confidential mission for Government, and HMS Berenice, Captain Heneage Dundas, an even older but somewhat less worn sixty-four-gun two-decker, together with her tender the Ringle, an American schooner of the kind known as a Baltimore clipper, had been sailing in company ever since they met north and east of Cape Horn, about a hundred degrees of latitude or six thousand sea-miles away in a straight line, if straight lines had any meaning at all in a voyage governed entirely by the wind, the first coming from Peru and the coast of Chile, the second from New South Wales.

The Berenice had found the Surprise much battered by an encounter with a heavy American frigate: even more so by a lightning-stroke that had shattered her mainmast and, far worse, deprived her of her rudder. The two captains had been boys together, midshipmen and lieutenants: very old shipmates and very intimate friends indeed. The Berenice had supplied the Surprise with spars, cordage, storage and a remarkably efficient Pakenham substitute rudder made of spare topmasts; and the two ship's companies, in spite of an initial stiffness arising from the Surprise's somewhat irregular status, agreed very well together after two ardent cricket matches on the island of Ascension, where a proper rudder was shipped, and there was a great deal of ship-visiting as all three lay with loose flapping sails in the doldrums, a sweltering fortnight with melted tar dripping from the yards. Though unconscionably long, it was a most companionable voyage, particularly as the Surprise was able to do away with much of the invidious difference between deliverer and delivered by providing the sickly and under-manned Berenice with a surgeon, her own having been lost, together with his only mate, when their boat overturned not ten yards from the ship—neither could swim, and each seized the other with fatal energy—so that her people, sadly reduced by Sydney pox and Cape Horn scurvy, were left to the care of an illiterate but fearless loblolly-boy; and to provide her not merely with an ordinary naval surgeon, equipped with little more than a certificate from the Sick and Hurt Board, but with a full-blown physician in the person of Stephen Maturin, the author of a standard work on the diseases of seamen, a Fellow of the Royal Society with doctorates from Dublin and Paris, a gentleman fluent in Latin and Greek (such a comfort to his patients), a particular friend of Captain Aubrey's and, though this was known to very few, one of the Admiralty's—indeed of the Ministry's—most valued advisers on Spanish and Spanish-American affairs: in short an intelligence-agent, though on a wholly independent and voluntary basis.

Yet a surgeon, even if he may also be a physician with a physical bob and a gold-headed cane who has been called in to treat Prince William, the Duke of Clarence, is not a mainmast, still less a rudder: he may uphold the people's spirits and relieve their pain, but he can neither propel nor steer the ship; the Surprises had therefore every reason to feel loving gratitude towards the Berenices, and since they knew the difference between right and wrong at sea they made full acknowledgment of their obligations as they passed through the frigid, temperate and torrid zones and so to the merely wet and disagreeable climate of home waters; but at no time could they be brought to love the Berenice herself.

Their feelings were shared by the crew of the Ringle, very much so indeed; for both the frigate and the schooner were quite exceptionally weatherly vessels, fast, capable of sailing very close to the wind—the schooner wonderfully close—and almost innocent of leeway, while the much larger and more powerful two-decker was but a slug on a bowline. She got along well enough when the breeze was abaft the beam—she liked it plumb on the quarter best—but as it came forward so her people exchanged anxious looks; and when at last studdingsails could no longer stand and when the ship was hauled close to the wind, the bowlines twanging taut, all their exertions could not bring her to within six points, nor prevent her sagging most disgracefully to leeward, like a drunken crab.

Feeling ran high, especially on the Surprise's quarterdeck, where an unusually vicious blast, cutting against the tide on its turn, had soaked all hands; but below, in the great cabin, the two captains sat unmoved as the Berenice floundered along under topsails and courses, shipping a great deal of water and drifting to leeward at her usual horrid rate, while the Surprise kept exactly in her due station astern with no more than double-reefed topsails and a jib half in, and the Ringle even less. Both men knew that all seamanship could do was being done, and a long professional career had taught them not only to accept the inevitable but not to fret about it. Even before they struck soundings Heneage Dundas had suggested that the Surprise should ignore naval convention and part company, going ahead as fast as she chose.

'She ain't carrying dispatches,' replied Jack with a frown—a ship carrying them was excused from all ordinary decencies or politeness; forbidden indeed to delay for even a minute—so there the matter rested; and now, Dundas having dined and supped aboard the frigate, they sat there with a broad-bottomed decanter of port between them, half-hearing the stroke of the sea on the larboard bow and then on the starboard when the ship had gone about on yet another of her long legs, and the hanging lamp swung over the locker, intermittently lighting a backgammon board, a sea-going board with the men still held by their pegs in Jack Aubrey's improbable winning position.

'Well, you shall have her,' said Dundas, emptying his glass. 'And you shall have her with all her gear and her ground-tackle too.'

'Come, that is handsome in you, Hen,' said Jack. 'Thank you kindly.'

'But I will say this, Jack: you have the most infernal luck. You had no right even to save your gammon.'

'It was a damned near-run thing, I must admit,' said Jack, modestly; then after a pause he laughed and said, 'I remember your using those very words in the old Bellerophon, before we had our battle.'

'So I did,' cried Dundas. 'So I did. Lord, that was a great while ago.'

'I still bear the scar,' said Jack. He pushed up his sleeve, and there on his brown forearm was a long white line.

'How it comes back,' said Dundas; and between them, drinking port, they retold the tale, with minute details coming fresh to their minds. As youngsters, under the charge of the gunner of the Bellerophon, 74, in the West Indies, they had played the same game. Jack, with his infernal luck, had won on that occasion too: Dundas claimed his revenge, and lost again, again on a throw of double six. Harsh words, such as cheat, liar, sodomite, booby and God-damned lubber flew about; and since fighting over a chest, the usual way of settling such disagreements in many ships, was strictly forbidden in the Bellerophon, it was agreed that as gentlemen could not possibly tolerate such language they should fight a duel. During the afternoon watch the first lieutenant, who dearly loved a white-scoured deck, found that the ship was almost out of the best kind of sand, and he sent Mr Aubrey away in the blue cutter to fetch some from an island at the convergence of two currents where the finest and most even grain was found. Mr Dundas accompanied him, carrying two newly sharpened cutlasses in a sailcloth parcel, and when the hands had been set to work with shovels the two little boys retired behind a dune, unwrapped the parcel, saluted gravely, and set about each other. Half a dozen passes, the blades clashing, and when Jack cried out 'Oh Hen, what have you done?' Dundas gazed for a moment at the spurting blood, burst into tears, whipped off his shirt and bound up the wound as best he could. When they crept aboard a most unfortunately idle, becalmed and staring Bellerophon, their explanations, widely different and in both cases so weak that they could not be attempted to be believed, were brushed aside, and their captain flogged them severely on the bare breech. 'How we howled,' said Dundas. 'You were shriller than I was,' said Jack. 'Very like a hyena.'

Killick, his steward, had long since turned in, so Jack fetched more port himself; and after they had been drinking it for some time he noticed that Dundas was growing curiously silent.

Orders and bosun's pipes on deck, and the Surprise came smoothly about with no more than the watch, settling easily on the starboard tack.

'Jack,' said Dundas at last, in a tone that Jack had heard before, 'this is perhaps an improper moment, while I am swilling your capital wine . . . but you did speak of some charming prizes in the Pacific.'

'Certainly I did. We were required to act as a privateer, you know, and since I could not disobey my instructions we took not only some whalers, which we sold on the coast, but also a vile great pirate fairly stuffed with what she had taken out of a score of other ships: maybe two score.'

'Well, I tell you what it is, Jack. The glass is rising, as I dare say you have noticed.' Jack nodded, looking at his friend's embarrassed face with real compunction. 'That is to say, it is likely the weather will clear, with the wind backing west and even south of west: tomorrow or the next day we should run up the Channel and then we shall part company at last, with you putting into Shelmerston and me carrying right on to Pompey.' This, though eminently true, called for some further observation if it were to make much sense; but Dundas seemed incapable of going on. He hung his head, a pitiful attitude for so distinguished a commander.

'Perhaps you have a girl aboard that you would like landed somewhere else?' suggested Jack.

'Not this time,' said Dundas. 'No. Jack, the fact of the matter is that as soon as the Berenice makes her number and it is known in the town that she is at hand the tipstaffs will come swarming out of their holes and the moment I set foot on shore I shall be arrested—arrested for debt and carried off to a sponging-house. I suppose you could not lend me a thousand guineas? It is a terrible lot of money, I know. I am ashamed to ask for it.'

'In course I could. As I told you, I am amazingly flush—Crocus is my second name. But would a thousand be enough? What was the debt? It would be a pity to spoil the ship for a . . .'

'Oh, it would be amply enough, I am sure; and l am prodigiously obliged to you, Jack. I dare not come down on Melville at this point: it would be different if he loved me as much as he loves you, but the last time he showed me out of the door he called me an infernal trundle-thrift whoremonger and condemned me to this vile New Holland voyage in the Berenice.' Heneage's elder brother, Lord Melville, was at the head of the Admiralty, and he could do such things. 'No. The judgment was for five hundred odd—the same young person, I am sorry to say, or rather her infamous attorney—but even with legal charges and interest I am sure a thousand would cover it handsomely.'

They talked about arrest for debt, sheriff's officers, sponging-houses and the like for some time, with profound and dear-bought knowledge of the subject, and after a while Jack agreed that a thousand would see his friend clear until he could draw his long-overdue pay and see the factor who looked after his Scottish estate: with a vessel as slow and unwieldy and unlucky as the Berenice there could be no question of prize-money, above all on such an unpromising voyage.

'How happy you make me feel, Jack,' said Dundas. 'A draft on Hoare's—for you bank with Hoare's, as I well remember—will be like Ajax's shield when I go ashore.'

'There is nothing like gold for satisfying an attorney out of hand.'

'Truer word you never spoke, dear Jack.

But even if you had gold—you will never tell me you have gold, English gold, Jack?—it would take hours to tell out a thousand guineas.'

'God love you, Hen. All this morning and much of this afternoon Tom, Adams and I were counting and weighing like a gang of usurers, making up bags for the final sharing-out when we drop anchor in Shelmerston. The Doctor helped too, nipping about among our heaps and taking out all the ancient coins—there were some of Julius Caesar and Nebuchadnezzar, I think, and he clasped an Irish piece called an Inchiquin pistole to his bosom, laughing with pleasure—but he threw us out of our count and I was obliged to beg him to go away, far, far away. When he had gone we sorted and counted, sorted and counted and weighed, only finishing just before dinner. Those large bags on the left of the stern-window locker hold a thousand guineas apiece—they are part of the ship's share—while the smaller bags hold mohurs, ducats, louis d'ors, joes and all kinds of foreign gold by weight of five hundred each, and the chests all along the side and down in the bread-room hold sacks of a hundred in silver, also by weight: there are so many that the ship is a good strake by the stern, and I shall be glad when they are better stowed. Take one of those thousands on the left, then. I can make up the sum in a moment from the rest, but silver would be much too heavy for you to carry.'

'God bless you, Jack,' said Dundas, hefting the comfortable bag in his hand. 'Even this weighs well over a stone, ha, ha, ha!' and as he spoke four bells struck, four bells in the graveyard watch, This was almost immediately followed by an exchange of orders and distant cries on deck: they were not the routine noises that preceded going about, however, and both captains listened intently, Heneage still holding the bag poised in his hand, like a Christmas pudding. Some moments later a wet, one-armed midshipman burst in and cried 'Beg pardon, sir, but Mr Wilkins desires his compliments and duty and there is a ship about two miles to windward, he thinks a seventy-four, in any case a two-decker, and he don't quite like her answer to the private signal.'

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

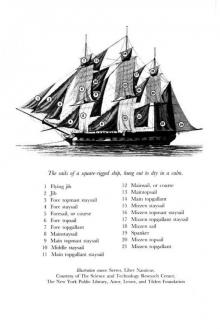

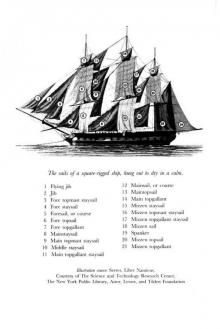

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea