- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

Master and Commander Page 4

Master and Commander Read online

Page 4

It was more than he had ever had, and more than he had ever really hoped for so early in his career; so why was there something as yet undefined beneath his exultation, the aliquid amari of his schooldays?

As he rowed back to the shore, pulled by his own boat's crew in white duck and straw hats with Sophie embroidered on the ribbon, a solemn midshipman silent beside him in the stern-sheets, he realized the nature of this feeling. He was no longer one of 'us': he was 'they'. Indeed, he was the immediately-present incarnation of 'them'. In his tour of the brig he had been surrounded with deference—a respect different in kind from that accorded to a lieutenant, different in kind from that accorded to a fellow human-being: it had surrounded him like a glass bell, quite shutting him off from the ship's company; and on his leaving the Sophie had let out a quiet sigh of relief, the sigh he knew so well: 'Jehovah is no longer with us.'

'It is the price that has to be paid,' he reflected. 'Thank you, Mr Babbington,' he said to the child, and he stood on the steps while the boat backed out and pulled away down the harbour, Mr Babbington piping, 'Give way now, can't you? Don't go to sleep, Simmons, you grog-faced villain.'

'It is the price that has to be paid,' he reflected. 'And by God it's worth it.' As the words formed in his mind so the look of profound happiness, of contained delight, formed once more upon his shining face. Yet as he walked off to his meeting at the Crown—to his meeting with an equal—there was a little greater eagerness in his step than the mere Lieutenant Aubrey would have shown.

Chapter Two

They sat at a round table in a bow window that protruded from the back of the inn high above the water, yet so close to it that they had tossed the oyster-shells back into their native element with no more than a flick of the wrist: and from the unloading tartan a hundred and fifty feet below them there arose the mingled scents of Stockholm tar, cordage, sail-cloth and Chian turpentine.

'Allow me to press you to a trifle of this ragoo'd mutton, sir,' said Jack.

'Well, if you insist,' said Stephen Maturin. 'It is so very good.'

'It is one of the things the Crown does well,' said Jack. 'Though it is hardly decent in me to say so. Yet I had ordered duck pie, alamode beef and soused hog's face as well, apart from the kickshaws. No doubt the fellow misunderstood. Heaven knows what is in that dish by you, but it is certainly not hog's face. I said, visage de porco, many times over; and he nodded like a China mandarin. It is provoking, you know, when one desires them to prepare five dishes, cinco platos, explaining carefully in Spanish, only to find there are but three, and two of those the wrong ones. I am ashamed of having nothing better to offer you, but it was not from want of good will, I do assure you.'

'I have not eaten so well for many a day, nor'—with a bow—'in such pleasant company, upon my word,' said Stephen Maturin. 'Might it not be that the difficulty arose from your own particular care—from your explaining in Spanish, in Castilian Spanish?'

'Why,' said Jack, filling their glasses and smiling through his wine at the sun, 'it seemed to me that in speaking to Spaniards, it was reasonable to use what Spanish I could muster.'

'You were forgetting, of course, that Catalan is the language they speak in these islands.'

'What is Catalan?'

'Why, the language of Catalonia—of the islands, of the whole of the Mediterranean coast down to Alicante and beyond. Of Barcelona. Of Lerida. All the richest part of the peninsula.'

'You astonish me. I had no notion of it. Another language, sir? But I dare say it is much the same thing—a putain, as they say in France?'

'Oh no, nothing of the kind—not like at all. A far finer language. More learned, more literary. Much nearer the Latin. And by the by, I believe the word is patois, sir, if you will allow me.'

'Patois—just so. Yet I swear the other is a word: I learnt it somewhere,' said Jack. 'But I must not play the scholar with you, sir, I find. Pray, is it very different to the ear, the unlearned ear?'

'As different as Italian and Portuguese. Mutually incomprehensible—they sound entirely unlike. The intonation of each is in an utterly different key. As unlike as Gluck and Mozart. This excellent dish by me, for instance (and I see that they did their best to follow your orders), is jabali in Spanish, whereas in Catalan it is senglar.'

'Is it swine's flesh?'

'Wild boar. Allow me . . .'

'You are very good. May I trouble you for the salt? It is capital eating, to be sure; but I should never have guessed it was swine's flesh. What are these well-tasting soft dark things?'

'There you pose me. They are bolets in Catalan: but what they are called in English I cannot tell. They probably have no name—no country name, I mean, though the naturalist will always recognize them in the boletus edulis of Linnaeus.'

'How . . .?' began Jack, looking at Stephen Maturin with candid affection. He had eaten two or three pounds of mutton, and the boar on top of the sheep brought out all his benevolence. 'How . . .?' But finding that he was on the edge of questioning a guest he filled up the space with a cough and rang the bell for the waiter, gathering the empty decanters over to his side of the table.

The question was in the air, however, and only a most repulsive or indeed a morose reserve would have ignored it. 'I was brought up in these parts,' observed Stephen Maturin. 'I spent a great part of my young days with my uncle in Barcelona or with my grandmother in the country behind Lerida—indeed, I must have spent more time in Catalonia than I did in Ireland; and when first I went home to attend the university I carried out my mathematical exercises in Catalan, for the figures came more naturally to my mind.'

'So you speak it like a native, sir, I am sure,' said Jack. 'What a capital thing. That is what I call making a good use of one's childhood. I wish I could say as much.'

'No, no,' said Stephen, shaking his head. 'I made a very poor use of my time indeed: I did come to a tolerable acquaintance with the birds—a very rich country in raptores, sir—and the reptiles; but the insects, apart from the lepidoptera, and the plants—what deserts of gross sterile brutish ignorance! It was not until I had been some years in Ireland and had written my little work on the phanerogams of Upper Ossory that I came to understand how monstrously1 had wasted my time. A vast tract of country to all intents and purposes untouched since Willughby and Ray passed through towards the end of the last age. The King of Spain invited Linnaeus to come, with liberty of conscience, as no doubt you remember; but he declined: I had had all these unexplored riches at my command, and I had ignored them. Think what Pallas, think what the learned Solander, or the Gmelins, old and young, would have accomplished! That was why I fastened upon the first opportunity that offered and agreed to accompany old Mr Browne: it is true that Minorca is not the mainland, but then, on the other hand, so great an area of calcareous rock has its particular flora, and all that flows from that interesting state.'

'Mr Brown of the dockyard? The naval officer? I know him well,' cried Jack. 'An excellent companion—loves to sing a round—writes a charming little tune.'

'No. My patient died at sea and we buried him up there by St. Philip's: poor fellow, he was in the last stages of phthisis. I had hoped to get him here—a change of air and regimen can work wonders in these cases—but when Mr Florey and I opened his body we found so great a . . . In short, we found that his advisers (and they were the best in Dublin) had been altogether too sanguine.'

'You cut him up?' cried Jack, leaning back from his plate.

'Yes: we thought it proper, to satisfy his friends. Though upon my word they seem wonderfully little concerned. It is weeks since I wrote to the only relative I know of, a gentleman in the county Fermanagh, and never a word has come back at all.'

There was a pause. Jack filled their glasses (how the tide went in and out) and observed, 'Had I known you was a surgeon, sir, I do not think I could have resisted the temptation of pressing you.'

'Surgeons are excellent fellows,' said Stephen Maturin with a touch of acerbity. 'And where should we be

without them, God forbid: and, indeed, the skill and dispatch and dexterity with which Mr Florey at the hospital here everted Mr Browne's eparterial bronchus would have amazed and delighted you. But I have not the honour of counting myself among them, sir. I am a physician.'

'I beg your pardon: oh dear me, what a sad blunder. But even so, Doctor, even so, I think I should have had you run aboard and kept under hatches till we were at sea. My poor Sophie has no surgeon and there is no likelihood of finding her one. Come, sir, cannot I prevail upon you to go to sea? A man-of-war is the very thing for a philosopher, above all in the Mediterranean: there are the birds, the fishes—I could promise you some monstrous strange fishes—the natural phenomena, the meteors, the chance of prize-money. For even Aristotle would have been moved by prize-money. Doubloons, sir: they lie in soft leather sacks, you know, about so big, and they are wonderfully heavy in your hand. Two is all a man can carry.'

He had spoken in a bantering tone, never dreaming of a serious reply, and he was astonished to hear Stephen say, 'But I am in no way qualified to be a naval surgeon. To be sure, I have done a great deal of anatomical dissection, and I am not unacquainted with most of the usual chirurgical operations; but I know nothing of naval hygiene, nothing of the particular maladies of seamen . . .'

'Bless you,' cried Jack, 'never strain at gnats of that kind. Think of what we are usually sent—surgeon's mates, wretched half-grown stunted apprentices that have knocked about an apothecary's shop just long enough for the Navy Office to give them a warrant. They know nothing of surgery, let alone physic; they learn on the poor seamen as they go along, and they hope for an experienced loblolly boy or a beast-leech or a cunning-man or maybe a butcher among the hands—the press brings in all sorts. And when they have picked up a smattering of their trade, off they go into frigates and ships of the line. No, no. We should be delighted to have you—more than delighted. Do, pray, consider of it, if only for a while. I need not say,' he added, with a particularly earnest look, 'how much pleasure it would give me, was we to be shipmates.'

The waiter opened the door, saying, 'Marine,' and immediately behind him appeared the red-coat, bearing a packet. 'Captain Aubrey, sir?' he cried in an outdoor voice. 'Captain Harte's compliment.' He disappeared with a rumble of boots, and Jack observed, 'Those must be my orders.'

'Do not mind me, I beg,' said Stephen. 'You must read them directly.' He took up Jack's fiddle and walked away to the end of the room, where he played a low, whispering scale, over and over again.

The orders were very much what he had expected: they required him to complete his stores and provisions with the utmost possible dispatch and to convoy twelve sail of merchantmen and transports (named in the margin) to Cagliari. He was to travel at a very great pace, but he was by no means to endanger his masts, yards or sails: he was to shrink from no danger, but on the other hand he was on no account to incur any risk whatsoever. Then, labelled secret, the instructions for the private signal—the difference between friend and foe, between good and bad: 'The ship first making the signal is to hoist a red flag at the foretopmast head and a white flag with a pendant over the flag at the main. To be answered with a white flag with a pendant over the flag at the maintopmast head and a blue flag at the foretopmast head. The ship that first made the signal is to fire one gun to windward, which the other is to answer by firing three guns to leeward in slow time.' Lastly, there was a note to say that Lieutenant Dillon had been appointed to the Sophie, vice Mr Baldick, and that he would shortly arrive in the Burford.

'Here's good news,' said Jack. 'I am to have a capital fellow as my lieutenant: we are only allowed one in the Sophie, you know, so it is very important . . . I do not know him personally, but he is an excellent fellow, that I am sure of. He distinguished himself very much in the Dart, a hired cutter—set about three French privateers in the Sicily Channel, sank one and took another. Everyone in the fleet talked about it at the time; but his letter was never printed in the Gazette, and he was not promoted. It was infernal bad luck. I wonder at it, for it was not as though he had no interest: Fitzgerald, who knows all about these things, told me he was a nephew, or cousin was it? to a peer whose name I forget. And in any case it was a very creditable thing—dozens of men have got their step for much less. I did, for one.'

'May I ask what you did? I know so little about naval matters.'

'Oh, I simply got knocked on the head, once at the Nile and then again when the Généreux took the old Leander: rewards were obliged to be handed out, so I being the only surviving lieutenant, one came my way at last. It took its time, upon my word, but it was very welcome when it came, however slow and undeserved. What do you say to taking tea? And perhaps a piece of muffin? Or should you rather stay with the port?'

'Tea would make me very happy,' said Stephen. 'But tell me,' he said, walking back to the fiddle and tucking it under his chin, 'do not your naval appointments entail great expense, going to London, uniforms, oaths, levees . . .?'

'Oaths? Oh, you refer to the swearing-in. No. That applies only to lieutenants—you go to the Admiralty and they read you a piece about allegiance and supremacy and utterly renouncing the Pope; you feel very solemn and say "to this I swear" and the chap at the high desk says "and that will be half a guinea", which does rather take away from the effect, you know. But it is only commissioned officers—medical men are appointed by a warrant. You would not object to taking an oath, however,' he said, smiling; and then feeling that this remark was a little indelicate, a little personal, he went on, 'I was shipmates with a poor fellow once that objected to taking an oath, any oath, on principle. I never could like him—he was for ever touching his face. He was nervous, I believe, and it gave him countenance; but whenever you looked at him there he was with a finger at his mouth, or pressing his cheek, or pulling his chin awry. It is nothing, of course; but when you are penned up with it in the same wardroom it grows tedious, day after day all through a long commission. In the gun-room or the cockpit you can call out "Leave your face alone, for God's sake," but in the wardroom you must bear with it. However, he took to reading in his Bible, and he conceived this notion that he must not take an oath; and when there was that foolish court-martial on poor Bentham he was called as a witness and refused, flatly refused, to be sworn. He told Old Jarvie it was contrary to something in the Gospels. Now that might have washed with Gambier or Saumarez or someone given to tracts, but not with Old Jarvie, by God. He was broke, I am sorry to say: I never could like him—to tell you the truth, he smelt too—but he was a tolerably good seaman and there was no vice in him. That is what I mean when I say you would not object to an oath—you are not an enthusiast.'

'No, certainly,' said Stephen. 'I am not an enthusiast. I was brought up by a philosopher, or perhaps I should say a philosophe; and some of his philosophy has stuck to me. He would have called an oath a childish thing—otiose if voluntary and rightly to be evaded or ignored if imposed. For few people today, even among your tarpaulins, are weak enough to believe in Earl Godwin's piece of bread.'

There was a long pause while the tea was brought in. 'You take milk in your tea, Doctor?' asked Jack.

'If you please,' said Stephen. He was obviously deep in thought: his eyes were fixed upon vacancy and his mouth was pursed in a silent whistle.

'I wish . . .' said Jack.

'It is always said to be weak, and impolitic, to show oneself at a disadvantage,' said Stephen, bearing him down. 'But you speak to me with such candour that I cannot prevent myself from doing the same. Your offer, your suggestion, tempts me exceedingly; for apart from those considerations that you so obligingly mention, and which I reciprocate most heartily, I am very much at a stand, here in Minorca. The patient I was to attend until the autumn has did. I had understood him to be a man of substance—he had a house in Merrion Square—but when Mr Florey and I looked through his effects before sealing them we found nothing whatever, neither money nor letters of credit. His servant decamped, which may explain it: but his friends do

not answer my letters; the war has cut me off from my little patrimony in Spain; and when I told you, some time ago, that I had not eaten so well for a great while, I did not speak figuratively.'

'Oh, what a very shocking thing!' cried Jack. 'I am heartily sorry for your embarrassment, and if the—the res angusta is pressing, I hope you will allow me . . .' His hand was in his breeches pocket, but Stephen Maturin said 'No, no, no,' a dozen times smiling and nodding. 'But you are very good.'

'I am heartily sorry for your embarrassment, Doctor,' repeated jack, 'and I am almost ashamed to profit by it. But my Sophie must have a medical man—apart from anything else, you have no notion of what a hypochondriac your seaman is: they love to be physicked, and a ship's company without someone to look after them, even the rawest half-grown surgeon's mate, is not a happy ship's company—and then again it is the direct answer to your immediate difficulties. The pay is contemptible for a learned man—five pounds a month—and I am ashamed to mention it; but there is the chance of prize-money, and I believe there are certain perquisites, such as Queen Anne's Gift, and something for every man with the pox. It is stopped out of their pay.'

'Oh, as for money, I am not greatly concerned with that. If the immortal Linnaeus could traverse five thousand miles of Lapland, living upon twenty-five pounds, surely I can . . . But is the thing in itself really feasible? Surely there must be an official appointment? Uniform? Instruments? Drugs, medical necessities?'

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

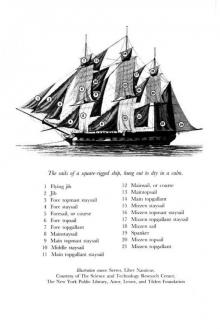

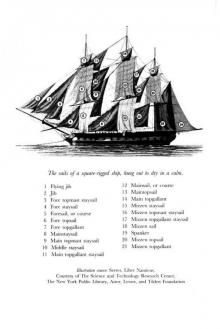

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea