- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure Page 3

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure Read online

Page 3

The swirl which he made, reaching the ball, brought it right across his path, and the attacking whale bit at it in his anger.

Instantly a great wall of green water shot up with a sky-splitting explosion, and Skogula was rolled over and over by the terrific force of it and felt his jaw slip back into position. A moment later a shower of blood-stained water and blubber and bones rained down from the sky – all that was left of Skogula’s enemy – the sixty-four foot sperm whale, after the contact mine had done its work.

PYTHON

IV

Python

In the humid depths of an African jungle the heat of midday struck down on to the tropical foliage and made even the sodden ground steam.

At noon there was not a sound except the monotonous hum of countless insects; all the animals were sleeping. Suddenly a shrill, almost human scream roused the hordes of monkeys which swarmed in those parts. The scream was followed by the querulous chattering of hundreds of the little beasts. One of their number had been caught by a python.

This python was a huge snake, fully thirty feet long, and as thick in the middle as a man’s thigh; he would eat anything from a frog to a man, but he preferred monkeys.

Very slowly he would creep up a tree, looking so like a strand of the great parasitical creepers that even the keen-eyed monkeys were deceived, and when he reached a suitable branch he would lie along it and wait for his food to come along.

This python’s particular hunting-ground lay along the banks of a swampy river. Here game was plentiful, and the python had lived well for many years. More years, indeed, than he could count, for although he was an intelligent beast, he could not recall happenings which took place before about ten castings of his skin.

His only rivals were leopards, who took monkeys; and the crocodiles in the river, who took the deer when they came down to drink in the evening. The python had long cherished a grievance against one particular leopard, who was constantly poaching on his preserves, and also against one huge, fat old crocodile who lived solitarily in a pool over which hung many trees.

This crocodile, not content with stealing the monkeys who fell into the water when the python had missed them at his first strike, had also snapped up drinking deer from under the python’s very nose.

One day, therefore, when he had just finished changing his skin, a painful process, the python, who was feeling discontented, decided to do away with both of his enemies as soon as possible.

He thought that he would deal with the crocodile first, as the leopard generally hunted at night. When he had finished his monkey, which he swallowed whole, the python dropped ten feet of his body on to a branch below. He curled his tail round this lower branch and dropped the rest of his length down to it. This branch led, like a road, to trees which in their turn led to the river.

Thus the great snake went fully half a mile without touching the ground. Throughout his own hunting-ground the python knew similar roads which led to all parts of his domain.

When he reached the river the python drank deeply and had a swim to loosen his new skin, which was rather tight.

He swam very fast, without effort, with about twenty-five feet of his length under the surface, and his head raised above it. He swam down the river to the pool where the crocodile lived. The whole river was inhabited by crocodiles, but none of them cared to touch the python when they saw him swimming past.

When he came near the pool he lowered his body in the water until only his head and a few inches of neck was visible above the surface. But for all that the old crocodile, stretched out on a mudflat near the bank, saw him out of one eye.

The crocodile was a blunt-nosed mugger, a villainous old man-eater who was fully the python’s equal in years.

Lying on his mudflat with his mouth open and the crocodile-birds hopping in and out of his teeth, the mugger saw the python, but did nothing.

The snake gained the bank and went up an overhanging tree. There he coiled himself in the crotch of the tree and watched the crocodile. They watched one another without winking for more than an hour; the snake because he had no eyelids with which to wink, and the crocodile because he felt the intense animosity of the python, and was too suspicious to lose sight of him for a second.

The day wore on eventlessly, but a little before dusk a baby monkey fell out of a tree next to the python’s; it lay on the ground whimpering, but its mother was too terrified to come to it, as she had seen the python move.

As the little monkey hit the ground the mugger slid noiselessly from his mudbank and reached the shore with hardly a ripple to show that he had moved.

For the moment the python had gone right out of his mind, for if there was anything for which the mugger would swim a mile, it was a baby monkey.

The crocodile waddled awkwardly but rapidly up the bank, and snapped up the monkey. On the land he was at a disadvantage; he knew it, and was turning to go when the python dropped on him.

For a moment the snake’s great weight crushed the breath out of the mugger, and he did not move.

Instantly the python flung two coils round the crocodile’s mouth, and held it closed as in a vice. The crocodile knew that if he did not reach the water before the snake had coiled about his tail and body, he would never survive the fight.

He made a desperate effort, and digging his stout claws into the sand he shuffled towards the river.

But the sand gave way beneath him, and the python had his tail curled round the trunk of a tree, so the mugger did not gain a foot. He lashed furiously with his powerful tail, but the python put a coil round it for all that.

Then the crocodile tried tearing at the snake with his strong claws, but there was not an inch of the python within reach.

He knew then that his only hope was to lie flat against the ground to prevent the python from coiling round his body. Imperceptibly the coils about his head and tail tightened, and the python began to draw him farther up the shore by pulling on the tree round which he had coiled his tail.

The mugger felt himself being dragged backwards, and made a despairing effort. The python’s tail lost its hold, and the two plunged into the river, closely intertwined.

By the time they had got to deep water, however, the snake had put three coils about the crocodile’s body.

The mugger fought desperately, tearing at the coils with all his strength. But it was of no avail, the coils tightened, his spine broke, and he died.

When he had made sure that the mugger was dead, the python swam to the shore, leaving the body to be eaten by the other crocodiles. On examining his wounds he found that although his new skin was torn in two or three places, the crocodile had not hurt him at all badly.

Towards nightfall he heard a leopard’s coughing roar behind him in the forest. He went with his usual unhurried speed towards the noise, and soon he came to a branch on which he picked up the leopard’s scent. He knew at once that it was not his enemy who had passed there, but another leopard.

Until moonrise he waited in a tree in which he had often seen the leopard, and a little after the full moon came up he saw him trotting along on the ground between the trees, evidently following some trail.

Very quietly he followed the leopard, gliding from tree to tree more like a wraith than a thirty-foot python.

The scent was strong, and the leopard never hesitated until he came to a clearing. In the middle of the open space a kid was tethered. The leopard sprang noiselessly into a tree; he had not seen the python.

The leopard crept to the end of a branch which overhung the clearing. The python climbed to a similar branch immediately above the leopard, who was completely absorbed in watching the kid. The great cat crouched flat against the branch; its spotted skin was almost invisible in the moonlight dappled with the shadows of twigs: only the tip of its tail moved, twitching feverishly from side to side.

The python saw the great muscles between the leopard’s shoulders swell and tauten as he prepared to spring, and the snake knew

that the time had come to strike.

Accordingly he wound five feet of his tail round the branch, and prepared to let the rest of himself drop and coil about the leopard. But the leopard sprang a second before the python had expected, and the snake missed his aim.

The leopard streaked on to the ground and sprang at the kid. Before he reached it, however, he was knocked head over heels backwards, for a rifle bullet hit him as he was in mid-air. A white hunter had tethered the kid there as a trap for the leopard, and he had been waiting since midday in a machan which he had built in a tree close by.

The leopard was killed at once, and after a second shot to make sure, the man came awkwardly down from his tree, for he was cramped by his long vigil.

He carried a revolver in his hand in case the leopard was only shamming. He came just under the tree in which the python had recoiled himself, and having made certain that the leopard had really passed out, he put the revolver back in its holster.

The python liked men; they tasted like fat, soft monkeys. He had already eaten three.

The hunter never had a hint of the python’s presence until he felt a coil round his chest. He made a dash for the open, but the coil tightened, and quickly the python hitched two more round him.

In a second the coils were so tight that the man could not draw breath, let alone call for help; but he still had one arm free, and he plucked furiously at his revolver.

The snake let the rest of his body down to the ground, and tightened the coils a little more. Some ribs gave way and the man felt himself losing consciousness, but he made a prodigious effort, and pulled the revolver clear of its holster. The python threw three more coils round his legs, and tightened them. If he had not been so worn out by his fight with the mugger he would have finished his puny adversary much sooner. He raised his head to the level of the man’s face in order to throw a coil round his neck.

This was a fatal mistake; the man raised his revolver with his free arm and blew the python’s head off.

There was a pause, then the coils slackened and lost their grip, falling away from the hunter.

The white man blew a whistle for his native servants, who were encamped nearby, and collapsed. They carried him back on a litter, for many of his ribs were broken.

On the next day, being of a frugal turn of mind, he had the python skinned as well as the leopard; the python’s skin became handbags, and the leopard’s a hearthrug.

THE CONDOR OF QUETZALCOATL

V

The Condor of Quetzalcoatl

One of the highest passes in the Andes runs past an ancient temple of Quetzalcoatl, a great god of the ancient Aztecs, who is still worshipped by some of the Indians, and this pass is called the Pass of Quetzalcoatl.

For about a mile at its highest point, this pass is a ledge barely a yard wide in places, which runs like a tiny crack across the face of an immense precipice.

The Andes rise above the pass up into the clouds, and the precipice falls sheer away from the ledge down into a valley of pines an incredible distance below.

There was another ridge high above the pass, a small piece of rock jutting out from the face of the precipice. It was entirely inaccessible to anything without wings, and on it there lived an immense condor.

This condor was famous throughout the mountainous country about the pass, and the Indians called him the condor of Quetzalcoatl; he was easily distinguishable from other condors by his enormous wing-spread, which marked him as a giant even among such huge-winged birds as his fellow condors.

The pass of Quetzalcoatl was rarely used since the Spaniards conquered South America, for the gold mines to which it led were hidden so well by the Indians that they have never been found.

About once a month, however, the little Indian village sent a load of moderately rich silver ore south over the pass to Pontrillo, where it was exchanged for the various things that the Indians wanted.

The ore was carried by a train of about a dozen of the sure-footed llamas which the Indians have used since time immemorial as pack animals.

An old Indian called Pepe usually took the llamas over the pass, as he knew it very well. The village also sent him because he had a shrewd eye for a bargain, and would get more value for the silver ore from the merchants of Pontrillo than anyone else.

Now it happened that for about a week before the llama train was due to cross the pass, the condor of Quetzalcoatl had been having very bad hunting. Indeed, he had not had a full meal for some days.

As he wheeled effortlessly thousands of feet above the pass, cutting great circles in the clear air, he noticed Pepe leading the heavily laden llamas.

The Indian saw the condor, and he waved to the bird, for he knew it quite well, having watched it every time he crossed the pass. It gave Pepe a curiously pleasant feeling which was at the same time slightly melancholy, to see the great condor wheeling up on motionless wings into the intense blueness of sky.

As the llamas came to the very narrow part of the ledge which ran under the condor’s eyrie, Pepe stopped watching the bird, and concentrated all his attention on getting his heavily laden animals safely across the dangerous part of the pass.

The llamas were loosely roped, head to tail, so that they should keep in a line, but the rope was very thin, so that if one fell the rope would break, and the falling llama would not drag all the others with it.

Just at the very thinnest part of the ledge the rearmost llama slipped, and fell on to its knees, hurting itself quite badly. Its load was too heavy for it to get to its feet again, so Pepe crept back along the edge of the pass, pushing the llamas against the face of the rock to enable himself to get past.

Hung motionless on the wind, the condor’s keen eyes marked every detail of the accident.

Pepe was having some difficulty in getting the llama to its feet, and as he pushed between it and the sheer rock, one of its hind feet went over the edge.

The condor turned his head to the earth and shot down a thousand feet, then he steadied himself, and stooped in an immense curve, striking the llama in the middle of the back.

The condor came down at a tremendous speed, but so accurate was his judgment that he shot between the animal and the rock face, passing immediately over Pepe’s head.

The llama tottered for a moment, and then fell from the ledge, overbalanced by its heavy load. The thin rope broke with a clear snap. Pepe saw the llama turn several times in the air; it seemed no larger than the palm of his hand when it struck the ground.

The condor dropped after it like a plummet, and Pepe cursed it by all the saints of Christendom and by all the gods of the Inca pantheon. Then he scrambled along the ledge to the head of the train, and led them carefully over the dangerously narrow path.

When they reached the part where the path widened into a safe road, Pepe let them take their own way, and strolled along behind, cursing the condor.

The dead llama had belonged to Pepe; it had been one of the three which he had bought some time ago. The rest of the train belonged to the other villagers.

Pepe arrived in Pontrillo before sunset, but he was distracted by the thought of his loss, and made a very poor bargain with the astute merchants.

He set out before sunrise the next day, for it was a full day’s journey home.

The llamas were only lightly laden with the things from the town. They passed under the eyrie at high noon, and Pepe saw the condor sitting there, full gorged and motionless.

He threw a stone at the bird, but the eyrie was far out of reach, so he shook his fist, and cursing the condor, passed on.

The villagers were sympathetic enough not to comment on the very poor bargain Pepe had made with their silver ore, but for several days he was quite morose, brooding over his loss.

In a month’s time the llama train set out again; Pepe had armed himself with a long stick, as there were no firearms in the village.

The condor had been looking out for the llama train for some time, and he followed it at a g

reat height until they came to the dangerous part of the pass, when the bird swung into the wind and hung quite still over the thinnest part of the ledge, watching every movement of the llamas very keenly.

Pepe urged his animals right in against the face of the rock, and walked behind them, watching the condor.

He felt quite sure that the condor would attack the rearmost animal again so he prepared for it, giving the last beast a light burden so that it would not overbalance.

He kept the llamas at a trot so as to get them past the dangerous ledge quickly. He looked at the condor, who was so high that he looked like a floating black feather.

Suddenly the great black bird raised his wings over his head, and dropped; he had seen the foremost llama getting nearer the edge. He checked at a thousand feet above the pass, and paused, judging that there was not quite room to swoop between the llama and the precipice.

Pepe saw what the condor was aiming at, and ran along the ledge to the front of the train.

There was only just room for him to stand on the edge and push the front llama back; this took all his attention.

He heard a rush of wings as the condor stooped on him. He caught a glimpse of broad black pinions, and then he knew that he was falling.

His only feeling was one of intense surprise as he saw the llamas on the pass apparently shooting up into the heavens.

Then he turned in the air and saw the ground rushing up at him incredibly quickly. He had no time to be afraid before he struck it.

The last thing he saw was a huge blue butterfly that flashed past him.

The bewildered llamas made their way back to the village after two days. The villagers, headed by Pepe’s son, Iturrioz, set out to look for him. They knew his skeleton by his necklace of red Indian gold; there was nothing else to know him by, for the twenty-three great condors who had followed the condor of Quetzalcoatl had only left the larger bones.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

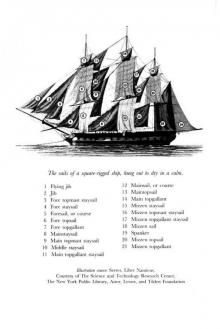

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

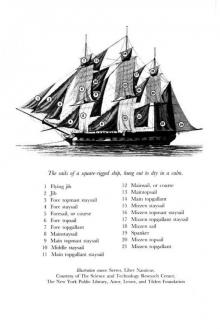

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea