- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

A Book of Voyages Page 3

A Book of Voyages Read online

Page 3

At Soumi I conversed with a brother of Prince Kourakin’s and a Mr. Lanskoy, both officers quartered there; and to whom I was indebted for a lodging: they obliged a Jew to give me up a new little house he was upon the point of inhabiting—The thaw had come on so quickly that I was obliged to stay two days while my carriages were taken off the sledges—

There is no gentleman’s house at Pultawa; I slept at my banker’s, and walked all about the skirts of the town—

CHERSON, MARCH 12, 1786

This place is situated upon the Dneiper, which falls into the Black sea; the only inconvenience of the Docks here is that the ships, when built, are obliged to be taken with camels into that part of the channel deep enough to receive them—The town is not at present very large, though there are many new houses and a church built after pretty models; good architecture of white stone—There are no trees near this place; [Colonel] Korsakof is trying to make large plantations; the town is entirely furnished with fuel by reeds, of which there is an inexhaustible forest in the shallows of the Boristhenes, just facing Cherson—Rails, and even temporary houses are made of them—Korsakof, and a Captain Mordwinof, who both have been educated in England, will, I have no doubt, make a distinguished figure in the military annals of Russia; Mordwinof is a sea-officer, and superintends the ship-building here—there are some very pretty frigates on the stocks. Repninskai is the governor’s name, and he has a young wife, who is very civil; my lodging is a large house built for a Greek Archbishop—but, being empty, was appropriated to my use: I have remonstrated here, but in vain, against having centinels, and the guard turning out as I pass through the gates. The Emperor’s Consul has a wife who wears a Greek dress here; I think it by no means becoming—I have nothing but maps and plans of various sorts in my head at present, having looked over all such as my curiosity could induce me to ask for—The fortifications and plantations are executed here by malefactors, whose chains and fierce looks struck horror into my heart, as I walked over them, particularly when I was informed there are between three and four thousand—

Mordwinof informs me, the frigate which is to convey me to Constantinople is prepared, and is to wait my pleasure at one of the seaports in the Crimea, and that the Comte de Wynowitch, who commands at Sevastopole has directions to accommodate me in the best manner—

KARASBAYER, APRIL 3, 1786

I went in a barge for about two hours down the Boristhenes, and landed on the shore opposite to that on which Cherson stands. A carriage and horses belonging to a Major who commands a post about two hours drive from the place where I landed were waiting, and these conveyed me to his house, where I found a great dinner prepared, and he gave me some excellent fresh-butter made of Buffalo’s milk; this poor man has just lost a wife he loved, and who was the only delight he could possess in a most disagreeable spot, marshy, low, and where he can have no other amusement but the troops—From thence I crossed the plains of Perekop, on which nothing but a large coarse grass grows, which is burnt at certain periods of the year—All this country, like that between Cherson and Chrementchruk, is called Steps—I should call it desert; except where the post-horses are found, not a tree not a habitation is to be seen—But one thing which delighted me much, for several miles after I had quitted Cherson, was the immense flocks of birds—bustards, which I took at a certain distance for herds of calves—and millions of a small bird about the size of a pigeon, cinnamon colour and white—droves of a kind of wild small goose, cinnamon colour, brown, and white.

Just without the fortress of Perekop I was obliged to send one of my servants to a Tartar village to get a pass; the servant whom I sent, whose ridiculous fears through the whole journey have not a little amused me, came back pale as death—He told me the chiefs were sitting in a circle smoking, that they were very ill black-looking people—I looked at the pass, it was in Turkish or Tartarian characters. I saw there two camels drawing a cart—This village gave me no great opinion of Tartarian cleanliness, a more dirty miserable looking place I never saw—The land at Perekop is but six miles across from the sea of Asoph, or rather an arm of it called the Suash, to the Black Sea—The Crimea might with great ease be made an island; after leaving Perekop, the country is exactly like what we call downs in England, and the turf is like the finest green velvet—The horses flew along; and though there was not a horse in the stables of the post-houses, I did not wait long to have them harnessed; the Cossacks have the furnishing of the horses—and versts or mile-stones are put up; the horses were all grazing on the plain at some distance, but the instant they see their Cossack come out with a little corn the whole herd surrounds him, and he takes those he pleases—The posts were sometimes in a deserted Tartarian village, and sometimes the only habitation for the stable-keeper was a hut made under ground, a common habitation in this country, where the sun is so extremely hot, and there is no shade of any sort. To the left of Perekop I saw several salt lakes about the third post—it was a most beautiful sight. About sun-set, I arrived at a Tartarian village, of houses or rather huts straggling in a circle without fence of any kind—I stopped there and made tea; that I might go on, as far as I could that night—You must not suppose, my dear Sir, though I have left my coach and harp at Petersburgh, that I have not all my little necessities even in a kibitka—a tin-kettle in a basket holds my tea equipage, and I have my English side-saddle tied behind my carriage—What I have chiefly lived upon is new milk, in which I melt a little chocolate. At every place I have stopped at I asked to taste the water from curiosity, I have always found it perfectly good—

I can easily suppose people jealous of Prince Potemkin’s merit; his having the government of the Tauride, or commanding the troops in it, may have caused the invention of a thousand ill-natured lies about this new country, in order to lessen the share of praise which is his due, in the attainment of preservation of it—but I see nothing at present which can justify the idea of the country’s being unwholesome.

KARASBAYER, APRIL 4, 1786

About half an hour after ten last night I ordered my servants not to have the horses put to, as I intended to sleep; I had not an idea of getting out of it, as our Post was a vile Tartar village; in a few minutes the servants called me, and said, the General’s nephew and son were arrived to meet me, and very sorry to find I had quitted Perekop, as they had orders to escort me from thence. I opened my carriage and saw two very pretty looking young men; I told them I should certainly not think of detaining them; and we set off, nor did I suspect that there were any persons with me but them: at — o’clock I let down the forepart of my carriage to see the sun rise; when, to my great surprise, I saw a guard of between twenty and thirty Cossacks, with an officer, who was close to the fore-wheel of the carriage; upon seeing me he smiled and pulled off his cap—his companions gave a most violent shriek, and horses, carriages, and all increased their pace, so that the horses in the carriage behind mine took fright, ran away, and running against my carriage very nearly overturned it; and when I asked what occasioned this event, I found my Cossack escort, seeing my carriage shut, thought I was dead; as a Cossack has no idea that a person in health can travel in a carriage that is not open, and the shout I had heard, the smile I had seen, was the surprise they had felt, that the young English princess, as they called me, was alive; as they believed it was only my corpse that was conveying to Karasbayar to be buried—They always ride with long pikes, holding the points upwards; the Tartars ride with pikes, but they hold the ends of theirs to the ground—About six I passed the Tartar town of Karasbayar, lying to the left—and arrived at the General’s house, a very good one, newly built for the reception of the Empress; the General Kokotchki, his brother the governor, and almost all the general officers were up and dressed, upon the steps of the house I found myself in my night-cap, a most tired and forlorn figure, in the midst of well-powdered men, and as many stars and ribbons around me as if I had been at a birthday at St. James’s—I retired but rose again at one, dressed and dined, and looked about me; t

his house is situated near the river Karasou or Black-water, which bathes the lawn before the house, and runs in many windings towards the town; it is narrow, rapid, and very clear; this is a most rural and lovely spot, very well calculated to give the Empress a good opinion of her new kingdom, for so it may be called. I had a Cossack chief presented to me, a soldier-like white-haired figure, he wore a ribband and order the Empress had given him set round with brilliants—The general told me he was sorry he was not thirty years younger, as the Empress had not a braver officer in her service—In the evening, in an amazing large hall, several different bands of music played; and I heard the national songs of the Russian peasants—which are so singular that I cannot forbear endeavouring to give you some idea of them—One man stands in the midst of three or four, who make a circle round him; seven or eight make a second round those; a third is composed of a greater number; the man in the middle of this groupe begins, and when he has sung one verse, the first circle accompany him, and then the second, till they become so animated, and the noise so great, that it was with difficulty the officers could stop them—What is very singular they sing in parts, and though the music is not much varied, nor the tune fine, yet as some take thirds and fifths as their ear direct, in perfect harmony, it is by no means unpleasing—If you ask one of them why he does not sing the same note as the man before him—he does not know what you mean—The subjects of these ballads are, hunting, war, or counterfeiting the graduations between soberness into intoxication—and very diverting. As these singers were only young Russian peasants, they began with great timidity, but by little and little ended in a kind of wild jollity, which made us all laugh very heartily—The Governor’s residence is not here, but at a place called Atchmechet; he is only come here to meet and conduct me through the Crimea; he is a grave sensible mild man. I am told he has conciliated the Tartars to their change of sovereign very much by his gentleness and firmness—To their honour, I find none would stay who could not bear the idea of taking the oaths of allegiance—but are gone towards Mount Caucasus—They have repented since, but it was too late—All the country here is downs except the borders of vallies, where rice is cultivated, and what the Tartars call gardens, which I call orchards—I cannot tell you, Sir, with what respect and attention I am treated here, and how good-naturedly all the questions I ask are answered—

There is an Albanian Chief here, though his post is at Balaklava, a sea-port; he is distinguished by the Empress likewise for his bravery; his dress differs much from the Cossack; it is something like the ancient Romans—he is an elderly man too. In a day or two I shall take my leave of this place for Batcheserai, the principal town and formerly the chief residence of the Khans.

APRIL, 1786

In the evening I went in a carriage with the governor and general to Karasbayar—and on the road saw a mock battle between the Cossacks—As I was not apprised beforehand, I confess the beginning of it astonished me very much—I saw the Cossack guard on each side the carriage spring from their stirrups, with their feet on the saddle and gallop away thus with a loud shriek—The General smiled at my astonished looks—and told me the Cossack Chief had ordered an entertainment for me—and desired me to get out and stand on the rising part of the down, facing that where a troop of Cossacks was posted—which I saw advancing with a slow pace—a detached Cossack of the adverse party approached the troop, and turning round sought his scattered companions, who were in search like him of the little army—they approached, but not in a squadron, some on the left, some on the right, some before, some behind the troop—a shriek—a pistol fired, were the signals of battle—the troop was obliged to divide in order to face an enemy that attacked it on all sides—The greatest scene of hurry and agility ensued; one had seized his enemy, pulled him off his horse, and was upon the point of stripping himfn1, when one of the prisoner’s party came up, laid him to the ground, remounted his companion, and rode off with the horse of the first victor—Some flung themselves off their horses to tear their foe to the ground—alternately they pursued or were pursuing, their pikes, their pistols, their hangers all were made use of—and when the parties were completely engaged together, it was difficult to see all the adroit manoeuvres that passed—

I arrived at the town, and was led to the Kadi’s house, where his wife received me, and no male creature was suffered to come into the room, except the interpreter and a young Russian nobleman only twelve years of age. This woman had a kind of turban on, with some indifferent diamonds and pearls upon it. Her nails were dyed scarlet, her face painted white and red, the veins blue; she appeared to me to be a little shrivelled woman of near sixty, but I was told she was not above fifty—She had a kind of robe and vest on, and her girdle was a handkerchief embroidered with gold and a variety of colours—She made me a sign to sit down; and my gloves seeming to excite much uneasiness in her I took them off—upon which she drew near, smiled, took one of my hands between her’s, and winked and nodded as a sign of approbation—but she felt my arm up beyond the elbow, half way up my shoulder, winking and nodding—I began to wonder where this extraordinary examination would end—which it did there—Coffee was brought, and after that rose-leaves made into sweetmeats—both of which the interpreter obliged me to taste—the sweetmeats are introduced last, and among the Orientals they are a signal that the visit must end—Our conversation by the interpreter was not very entertaining—A Tartar house is a very slight building of one story only—no chair, table, or piece of furniture in wood to be seen—large cushions are ranged round the room, on which we sat or reclined—As the visit was at an end, I curtsied and she bowed.

BATCHESERAI, APRIL 8, 1786

In my way hither I dined at the Cossack Chief’s post—and my entertainment was truly Cossack—a long table for thirty people—at one end a half-grown pig roasted whole—at the other a half-grown sheep, whole likewise—in the middle of the table an immense tureen of curdled milk—there were several side-dishes made for me and the Russians, as well as the cook could imagine to our taste—The old warrior would fain have made me taste above thirty sorts of wine from his country, the borders of the Don; but I contented myself with three or four, and some were very good. After dinner from the windows, I saw a fine mock battle between the Cossacks; and I saw three Calmoucks, the ugliest fiercest looking men imaginable, with their eyes set in their head, inclining down to their nose, and uncommonly square jaw-bones—These Calmoucks are so dexterous with bows and arrows that one killed a goose at a hundred paces, and the other broke an egg at fifty—The young Cossack officers tried their skill with them, but they were perfectly novices in comparison to them—they sung and danced, but their steps and their tones were equally insipid, void of grace and harmony.

When a Cossack is sick he drinks sour milk for a few days, and that is the only remedy the Cossacks have for fevers—

At night I lodged at a house that had belonged to a noble Tartar, where there is a Russian post, with about twelve hundred of the finest men I ever saw, and uncommonly tall. A Tartarian house has always another building at a little distance from it, for the convenience of travellers or strangers, whom the noble Tartar always treats with the greatest hospitality—Here the General parted from us. I proceeded in the Governor’s carriage with him thus far; the rest of our company went to see Kaffa or Theodosia. I go to meet them tomorrow, at a place called Mangouss—We had only two Cossacks with us, as the General, to please the Tartars, never is escorted by a military party. Batcheserai is situated in so steep a valley, that some of the hanging pieces of rock seem ready to fall and crush the houses—About a mile from the town on the left, I saw a troop of well-dressed Tartars, there were above a hundred on horseback; the Kaima-Kanfn2 was at the head of this company, who were come out to meet and escort us, but I who did not know this, asked the Governor if there was a Russian post here, which there is above the town, of a thousand men—There are five thousand Tartar inhabitants here; I do not believe there was a man left in his house, the streets being lined

with Tartarian men on each side; their countenances were very singular, most of them kept their eyes fixed on the ground, as we passed; but some just looked up, and, as if they were afraid of seeing a woman’s face uncovered, hastily cast their eyes downward again; some diverted at the novelty, looked and laughed very much—There is a great trade here of blades for swords, hangers, and knives—I am assured many made here are not to be distinguished from those of Damascus—

The Khan’s palace is an irregular building, the greatest part of it is one floor raised upon pillars of wood painted and gilt in a fanciful and lively manner—the arch, or last doorway, has fine proportions, a large inscription in gilt letters is the chief ornament—I am told it was perfectly in ruins, but the Governor has had it repaired, new gilt, and painted for the Empress’s reception—Court within court, and garden within garden, make a variety of apartments where the Khan walked from his own residence to the Harem, which is spacious and higher than the other buildings—What I thought pretty enough was that several of the square places under his apartment were paved with marble, and have in the centre fountains which play constantly—My room is a square of more than forty feet, having two rows of windows one above the other on three sides, and it was with difficulty I found a place to have my bed put up in—

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

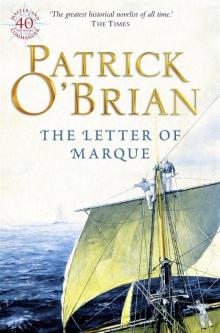

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

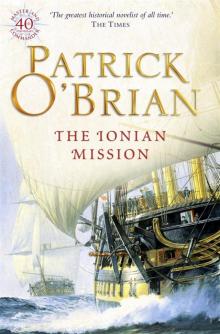

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

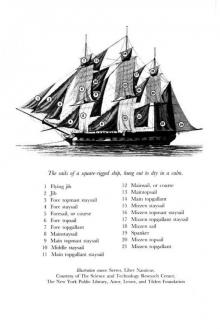

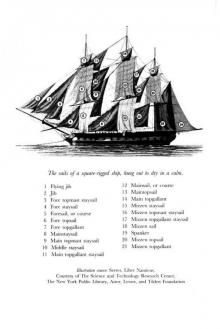

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea