- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Road to Samarcand Page 20

The Road to Samarcand Read online

Page 20

“Oh, well,” said Sullivan, “the general meaning is clear enough. It does not very much matter: now that we know exactly where the Red-Hats are, I dare say that by using a little common sense we shall be able to get by them.”

THEY HAD BEEN very pleased with Tanglha-Tso when they reached it, but when, at the end of many days they were still there, they began to detest the place. They were in a fever to get on: every day counted, and yet they could not get away. Every day there were excuses—the yaks were still on the summer pastures far away, the barley had not yet been threshed, they could not yet spare any men for guides. They were conscious of sour looks as they walked about the village, and they began to find that their few words of Tibetan were no longer understood. Their guides from Hukutu had gone back, and these people disclaimed any knowledge at all of Mongol. Then one day two of their yaks disappeared: nobody seemed to be responsible or interested. They made gestures that appeared to mean that the yaks had run off on their own. The next day a third was gone.

“What the devil is the matter with these people?” cried Sullivan, in exasperation. “If only the abbot were here, he would set about them, I’m sure.”

“I’ve a good mind to bang their silly heads together,” growled Ross, who had spent most of the morning offering little drawings of yaks, loads of food and other necessities to the few men who would pay any attention. One had taken the paper and put it in his prayer-wheel, in case it might do any good, but the others had been uncomprehending and uninterested.

“I have offered them money,” said Sullivan, banging his fist into his palm, “and they just stare at it and walk away. Flaming death!” he cried, “I shall start to get angry soon.”

“I do not think that this is a case where physical violence would serve our purpose,” said the Professor. “But I believe I have a clue to the trouble. It cannot have escaped your notice that Tibetan society has a matriarchal structure. The old woman in whose house we live is the virtual ruler of Tanglha-Tso—she is also, by the way, the abbot’s aunt, and in secular matters he goes in awe of her. The same applied at Hukutu. Now the Tibetan woman is not only a matriarch: she is also polyandrous.”

“Polly Andrews!” exclaimed Olaf.

“I mean she has several husbands. The old woman has four. Ngandze was his wife’s second husband, and thus occupied the position of a second wife in China.”

“Four husbands! Ay reckon she ban a wicked old beezle——”

“Olaf, pipe down,” cried Sullivan. “Please go on, Professor, and tell us more about Auntie.”

“Well, we have these two essential facts, matriarchy and polyandry. Now let us suppose that one of these women has taken it into her head to acquire one of us as a spare husband, would not that account for the delay, the black looks of the men and the general change of attitude? We must remember that these men are as much subjected to their wives as wives are to their husbands in other countries that are more civilised—in the United States, for example,” he said, bowing to Sullivan. “Does not my theory square with the facts? We have calculated delay, in order to detain the object of the woman’s passion. We have black looks from the men, either because they resent the intrusion of a stranger or because they had hoped to be chosen in his place. Furthermore, all this has taken place since the departure of the abbot, who would be the only other governing influence in the village. Does it not all point to a clearly defined intent on the part of the old lady whose name I have not yet caught, but whom, for the sake of argument, we will term Auntie?”

“Good Lord above,” exclaimed Ross with a groan, “I’m afraid you’re right.”

“Who is the man?” cried Sullivan, glaring round. “I’ll wring his—you don’t think she has picked on me, Professor, do you?” he asked, turning suddenly pale.

“No,” said the Professor. “I have been watching closely, and incredible as it may seem, I believe it is Olaf.”

“I never,” roared Olaf, starting up.

“You have been monkeying about with Auntie,” cried Sullivan, advancing upon him.

“No, no,” said the Professor, waving his hand, “I do not think any fault is to be attributed to Olaf. The choice appears to be entirely one-sided. Though upon my word,” he said, lowering his spectacles and gazing at Olaf over them, “I find it difficult to credit that a young woman . . . However, I am still not wholly convinced. We must watch them narrowly, cautiously, you understand, so that they will not notice, during this party to which it appears that we are invited this afternoon.”

“Have they really picked upon Olaf?” asked Derrick, in a wondering voice.

“Some resemblance to heathen idol,” said Li Han, “or perhaps local fabulous monster.”

“You quit that,” said Olaf, going redder still. “My face ban okay, see? Ay reckon it ban a natural choice. But Auntie . . . aw, shucks.”

“It is not Auntie who is the prime mover, in my opinion,” said the Professor. “It is rather that stout young matron whose name, I think, is Ayuz, Auntie’s daughter. But that, if anything, makes the choice even more extraordinary.”

“I would believe anything of people who put butter in their tea,” said Sullivan. After a minute of hard thought he said, “What are we to do? In a case of this kind it’s like being without a compass or a chart. If you’re right, and I fear you are, these infernal women will never let us get on the road until they have their way. I’ve had something to do with women, and they’re all the same: they always get you down in the end.”

“The first thing to do is to make sure of our suspicions,” said the Professor, “and then perhaps we can think of some plan to confound the sirens.”

A few hours later they were sitting in the largest room in Tanglha-Tso, facing the formidable old woman they called Auntie. Behind her stood three of her four husbands, meek men, all of them, and at her side stood the young, stout woman whom Olaf now called Polly Andrews: her hair was more thickly buttered than usual, and she wore a towering scarlet hat. In the background there were all the villagers who could squeeze in: the air was thick with smoke and heat.

“That girl ban nuts,” muttered Olaf. The words were hardly out of his mouth before Polly stepped forward and pinned a silver brooch, studded with turquoises, on to Olaf’s coat. He went as red as a beetroot. He sprang up, saying, “Why, thank you, marm,” and crashed his head against the ceiling. He sat down again, rubbing his head and muttering, “Aw, shucks.”

Polly went back to stand by the old woman, and she gazed unceasingly at Olaf while the old woman poured out a flood of words, mostly directed at the Professor, but some at Olaf, who sat there with an impassive countenance, wishing, above all things, to prove his innocence to the others.

Presently tea came in, and a jar of a sticky, greenish substance, very dark. They were all given bowls of buttered tea, but Olaf alone had something from the jar. Polly squatted by him and fed it to him from a spoon. He absorbed it without any expression whatever, but Derrick, squeezed firmly against him by the villagers, felt him tremble. From time to time Polly stroked Olaf’s golden hair and murmured loving words.

There was no doubt left in their minds at all, and they watched with profound misgiving.

When the tea was being carried away, the holder of the tea-pot did not move quickly enough to please Polly: she lifted her long coat and swung her boot forward in a kick that shot the attendant far out into the darkness.

“That young person has a will of her own,” remarked the Professor.

“Lifted him a yard,” muttered Olaf, nervously wiping his brow. “What ban Ay let in for?”

The old woman’s flow of words became slower, more emphatic. There were several scraps of Mongol in it: she clearly meant to be understood.

The Professor replied, and the room was silent, listening intently. He broke off, consulted his list of words, and went on.

The old woman began again, and all the eyes in the room, whether they could understand or not, turned to her. Then the Professor spoke, and

all the eyes swung back again. He said a long sentence. There was a gasp of horror from the Tibetans. He repeated it, pointing up towards the monastery, and they gasped again, gazing at Olaf and drawing away from him. The old woman started a long harangue, pointing at Olaf with one hand and waving a prayer-wheel with the other. The whole room stared at Olaf, edging still farther away. While they were doing this, the Professor pretended to consult his book, and behind it whispered rapidly to Sullivan, “Olaf must go mad when I strike the table. Let him shriek, and then knock him down. Pass it on.” The whisper ran down the line while the old woman was still speaking, but it did not reach Derrick, who was the other side of Olaf, and who was therefore petrified when, after the Professor had pronounced another sentence that made the Tibetans gasp and recoil so that the weaker members were crushed against the wall and cried out in agony, and had held up a charm with one hand while he banged the table with the other, Olaf suddenly rose in a weird, hunched attitude, drew his face into an appallingly contorted mask and began to shriek like a steam-whistle, “Hoo, hooo, hoooo.” At the same time he began to lurch madly from side to side and grasped at Derrick’s throat with hands like crooked claws. At this moment Ross and Sullivan hurled themselves upon Olaf, flung him to the earth and began to belabour him with their fists. But they could not master him: with wild heaves he flailed about, still pouring forth his hideous and deafening scream until the Professor stepped up to him, and holding the charm over him said, in a chanting voice, “Oh thou able seaman, hold thy tongue. Go limp, therefore, and look as meek and peaceable as thou conveniently mayest.”

Olaf relaxed, an expression of imbecile benignity overspread his weathered features, and he lay still.

But the horror and alarm—to which Derrick’s unfeigned astonishment had added—was too great for the Tibetans. They rushed madly into the night, and only the old woman and Polly, with one person who was too paralysed with fear, remained. The old woman was trembling, but she would not run: Polly, as pale as she could very well go, gestured faintly towards Olaf and whispered something. The Professor bent over Olaf, whispered, “Foam a little,” and unpinned the turquoise brooch. Olaf foamed like a whirlpool and twitched horribly. Polly took her brooch and vanished.

“I think it would be advisable if Olaf were now to crawl on his hands and knees through the street to our yaks,” said the Professor, sitting down. “Dear me, what an exhausting conversation.”

“How did you do it, Professor?” asked Sullivan, with admiration.

“I had in mind a passage in a book of travels by the Buddhist monk Yen Tzu, who was in these regions during the last days of the T’ang dynasty. I was by no means sure of my ability to convey the anecdote, but they seem to have caught the gist, though with heaven knows what distortions, because I have only the most general notion of the meaning of some of the words I employed. However, the story that I intended to convey was this: Yen Tzu, on one of his journeys, met a Siberian person who had captured a semi-human monster in the desert and had taken him to an abbot famous for his piety to have him entirely humanised—it appears that he was a serviceable monster. But the abbot had only been partially successful: with the waning of each moon—and I happened to notice that the moon was very small last night—the power of the charm diminished, and the monster returned to his habit of eating human flesh, female human flesh. He could only be subdued by a jade charm, and then only when it was held by his owner. This was the tale I adopted, using the convenient departure of our good friend the abbot as a circumstantial detail, and as far as I can see they understood and believed the greater part of it. At all events, I venture to prophecy that none of them will willingly encounter Olaf as he crawls about the streets, particularly if he continues to snort in that disagreeable fashion.”

From outside came the sound of Olaf ’s progress as he shuffled industriously round and round the narrow streets, grunting as he went, and scratching horribly at each door to strike terror and dismay into the silent and cowering inhabitants.

“I am really sorry to have added to the burden of superstition that weighs on these unfortunate people,” said the Professor, in another tone. “It would have been inexcusable if our need had not been so pressing: but I shall leave a letter, in the simplest Chinese that I can devise, to explain the situation to the abbot on his return, and I trust that he will be able to undo at least some of the mischief.”

“It was a wonderful feat, Professor,” said Sullivan. “Now I understand why you were drawing crescents and full moons on the table. But I hope we have not overdone it. I am quite sure that they will not want to keep Olaf in their bosoms any longer, but if they get so frightened that they won’t trade with us or lend us guides, then we shall be in a pretty fix.”

“I do not anticipate that,” replied the Professor. “Auntie is a very strong-minded woman, not at all unlike a Mrs. Williams, the wife of one of my colleagues. But perhaps it would be as well to restrain Olaf’s zeal at present. Derrick, will you take a chain and lead him to the yaks? He will have to spend the night out, poor fellow; but it is all in the common cause. And by the way, ask him to be so good as to provide himself with a short tail, will you? I mentioned, in passing, that he had one, in the course of my remarks. Perhaps he had better let it show a little in the morning—but discreetly, you understand?”

Sullivan’s fears were baseless. In the first light of the morning the village notables, all strong-minded females, gathered outside the house with their attendant husbands and a train of yaks. All the difficulties that had plagued them for so many days suddenly vanished: the barley was found to be threshed, men could be spared, food was abundant, the missing yaks were found, the Professor’s Tibetan was understood and several men remembered scraps of Mongol or Chinese.

Before the sun was well up the expedition was on its way again. The black looks of the men were gone, replaced by an anxious friendliness: they pressed little gifts on all the members of the party except Olaf, whom they regarded with unfeigned horror. He was obliged to walk forty yards behind the others, and whenever he approached nearer, the Tibetan guides thundered on a gong that they carried with them for the purpose, and blew on shrill-voiced horns, waving their prayer-wheels at the same time. He was obliged to be fed at a great distance from the fire, and after some days of this he became very melancholy and low in his spirits. He complained of the inconvenience of his tail, but when the Professor assured him that he would be reinstated as a human being when the new moon appeared he grew less despondent, and watched the waning moon with the keenest attention.

Their route led on and on, always to the west: it was never a marked road, except where it entered the villages, but the Tibetans followed it as though it had a pavement on either side. Up and down they went, sometimes ploughing knee-deep through the snow at fifteen thousand feet and more, sometimes panting in the heat of an enclosed valley roasting in the sun. They had game in abundance, and they dried many pounds of lean meat against emergencies to come. As the days went by they shortened Olaf’s tail inch by inch, and when the new moon showed a silvery sickle over the gleaming mountains that hemmed them in, he was allowed to put it away altogether. The Tibetans, with some misgivings, admitted him to the fireside again; but they would never sit near him if they could avoid it.

They had one bad snow-storm that caught them in one of the high passes and delayed them for two days. Olaf built one of his snow houses, but the Tibetans would have none of his monstrous practices, and huddled motionless against their shaggy beasts, who stood, quite unconcerned, while the snow covered them.

It was after this storm that they first met a great herd of yaks being brought down from the summer pastures: the next day they met two more, and they understood the herdsmen to say the early winter was coming on apace. “We must hurry,” said Sullivan, with a round, seafaring oath, as he tried to urge his stolid yak to a speed greater than a crawl. “If only those half-witted omadhauns had let us go, we would be a hundred miles farther on by now.”

&nbs

p; But the yaks would not be hurried: they kept to their invariable sluggish plod whatever happened, and if they were vexed with pulling, pushing or with blows they would dig all four feet in, close their large eyes and become absolutely immovable. Only when they smelt a snow-leopard—which was not rare when they were just above the snowline—would they run, and then, as often as not, they ran in the wrong direction.

But they were patient, incredibly hardy and enduring creatures, and wonderfully sure-footed. Only once did one ever fall, and that was at the ford of the river a little before the first Red-Hat monastery. The river was swollen, the load was badly tied, and the yak went down: nothing was lost except, by great bad luck, one single heavy little box that contained most of what ammunition they had not abandoned in their dreadful days above Hukutu. They dived for it in the freezing water, but it was at the bottom of a whirlpool, and they had to give it up. They were reduced now to a very few rounds apiece, and Sullivan gave the order that no one was to shoot except Ross, who could be relied upon never to waste a single shot.

They got by the first dangerous strip of country, however, with no difficulty at all, and although a week later at the second they saw what they took to be a party of lamas in the distance, they had no unpleasant encounters. The weather was holding up, and they were making good distance every day.

Their detour to pass the second lamasery had been arranged, by two forced marches, to coincide with the full moon, and it was wholly successful: they rejoined their road exactly where they meant, and followed a winding river—still clear and unfrozen—as they pushed on to Thyondze. But once the full moon began to wane, Olaf became an object of horror to the guides. He was made to keep a great way off, and this time, as the road was clear along the riverside, he elected to walk in front. Sometimes Derrick and Chingiz walked with him for company, although the Tibetans often urged them not to take the risk, and on the first day that they struck their road again, all three of them had been walking well ahead of the main party when Derrick remembered that he had left the barley-cakes and the dried meat that they were to eat at midday. He ran back to his yak. Sullivan was saying to the Professor, “We shall not be able to pass the third Red-Hat lamasery at Thyondze with the full moon: but I am not sure that it would not be better altogether to get by on a darker night. They tell me that there is a road so clear that we cannot miss it, and it turns so sharply to the left that we shall be out of sight of the monastery well before dawn—hullo, what’s that?” He broke off and pointed to the river. Bobbing down towards them on the broad and rapid stream there was something floating: it came nearer, and they saw that it was a tall felt hat, a red Tibetan hat.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

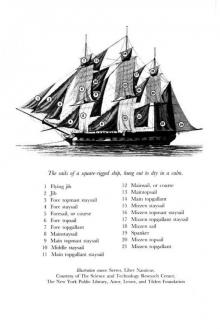

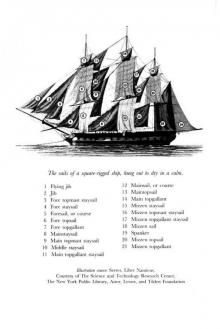

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea