- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Thirteen-Gun Salute Page 2

The Thirteen-Gun Salute Read online

Page 2

'Certainly,' said Stephen, 'if we accept that the only man present willing to carry ill-natured gossip was the worm in question.'

'Very true,' said Blaine. 'Still, it might give some slight hint or indication. But in any case, I do beg you will urge our friend to be discreet. Tell him that although the First Lord is an honourable man the present complexion of affairs is such that he may be physically incapable of fulfilling his promises; he may be excluded from the Admiralty. Tell Aubrey to be very cautious in his certainties; and tell him to put to sea as soon as ever he can. Tell him that quite apart from obvious considerations there are obscure forces that may do him harm.'

Jack Aubrey had little notion of his friend's mathematical or astronomical abilities and none whatsoever of his seamanship, while his performance at billiards, tennis or fives, let alone cricket, would have been contemptible if they had not excited such a degree of hopeless compassion; but where physic, a foreign language and political intelligence were concerned, Maturin might have been all the Sibyls rolled into one, together with the Witch of Edmonton, Old Moore, Mother Shipton and even the holy Nautical Almanack, and no sooner had Stephen finished his account with the words 'It is thought you might be well advised to put to sea quite soon. Not only would it place those concerned before a fait accompli but it would also—forgive me, brother—prevent you from committing yourself farther in some unguarded moment or in the event of provocation,' than Jack gave him a piercing look and asked 'Should I put to sea directly?'

'I believe so,' said Stephen.

Jack nodded, turned towards Ashgrove Cottage and hailed 'The house, ahoy. Ho, Killick, there,' in a voice that would quite certainly reach across the intervening two hundred yards.

He need not have called out so loud, for after a decent pause Killick stepped from behind the hedge, where he had been listening. How such an awkward, slab-sided creature could have got along by that sparse and dwarvish hedge undetected Stephen could not tell. This newly-planned bowling-green had seemed an ideal place for confidential remarks, the best apart from the inconveniently remote open down; Stephen had chosen it deliberately, but although he was experienced in these things he was not infallible, and once again Killick had done him brown. He consoled himself with reflecting that the steward's eavesdropping was perfectly disinterested—the true miser's love for coins as coins, not as a means of exchange—and that his loyalty to Jack's interests (as perceived by Killick) was beyond all question.

'Killick,' said Aubrey, 'sea-chest for tomorrow at dawn; and pass the word for Bonden.'

'Sea-chest for tomorrow at dawn it is, sir; and Bonden to report to the skittle-alley,' replied Killick without any change whatsoever in his wooden expression; but when he had gone a little way he stopped, crept back to the hedge again and peered at them for a while through the branches. There were no bowling-greens in the remote estuarine hamlet where Preserved Killick had been born, but there was, there always had been, a skittle-alley; and this was the term he used—used with a steady obstinacy typical of his dogged, thoroughly awkward nature.

And yet, reflected Stephen as they paced up and down as though on a green or at least greenish quarterdeck, Killick was nearly in the right of it: this had no close resemblance to a bowling-green, any more than Jack Aubrey's rose-garden looked like anything planted by a Christian for his pleasure. Most skills were to be found in a man-of-war—the Surprise's Sethians, for example, with only the armourer and a carpenter's mate to help them, had run themselves up a new meeting-house in what was understood to be the Babylonian taste, with a chain of great gilded S's on each of its marble walls—but in the present case gardening did not seem to be one of them. Certainly fine scything was not. The green was covered with crescent-shaped pecks where the ill-directed blade had plunged into the sward: some of the pecks were bald with a yellow surround, others were bald entirely; and their presence had apparently encouraged all the moles of the neighbourhood to throw up their mounds beside them.

It was the most superficial part of his mind that made these reflexions: below there was a mixture of surprise and consternation, largely wordless. Surprise because although he thought he knew Jack Aubrey very well he had clearly under-estimated the measureless importance he attached to every aspect of this voyage. Consternation because he had not meant to be taken literally. This 'sea-chest for tomorrow at dawn' would be exceedingly inconvenient to Stephen—he had a great deal of business to attend to before sailing, more than he could comfortably do even in the five or six days allotted—but he had so phrased his words, particularly the discourse that preceded the direct warning, that he could think of no way of going back on them with any sort of consistency. In any case, his invention was at a particularly low ebb; so was his memory—if he had recalled that the frigate was already fully victualled for her great voyage he would have been less oracular. He was in a thoroughly bad state of mind and temper, dissatisfied with the people in his banking-house, dissatisfied with the universities in which he meant to endow chairs of comparative anatomy; he was hungry; and he was cross with his wife, who had said in her clear ringing voice, 'I will tell you what, Maturin, if this baby of ours has anything like the discontented, bilious, liverish expression you have brought down from town, it shall be changed out of hand for something more cheerful from the Foundling Hospital.'

Of course in theory he could say 'The ship will not sail until I am ready', for absurdly enough he was her owner; but here theory was so utterly remote from any conceivable practice, the relations between Aubrey and himself being what they were, that he never dwelt on it; and in his hurry of spirits and the muddled thinking caused by ill-temper he hit upon nothing else before Bonden came at the double and the Goat's and the George's post-chaises were bespoke, express messengers sent off to Shelmerston, London and Plymouth; and even if Maturin had spoken with the tongues of angels it was now too late for him to recant with any decency at all.

'Lord, Stephen,' said Jack, cocking his ear towards the clock-tower in the stable-yard, a fine great yard now filled with Diana's Arabians, 'we must go and shift ourselves. Dinner will be ready in half an hour.'

'Oh for all love,' cried Stephen with a most unusual jet of ill-humour, 'must our lives be ruled by bells on land as well as by sea?'

'Dear Stephen,' said Jack, looking down on him kindly, though with a little surprise, 'this is Liberty Hall, you know. If you had rather take a cold pork pie and a bottle of wine into the summer-house, do not feel the least constraint. For my own part, I do not choose to disoblige Sophie, who means to put on a prodigious fine gown: I believe it is our wedding-day, or perhaps her mother's. And in any case Edward Smith is coming.'

As it happened Stephen did not choose to disoblige Diana either. They had recently had a larger number of disputes than usual, including a quite furious battle about Barham Down. The place was too large and far too remote for a woman living by herself; the grass was by no means suitable for a stud-farm she had seen the aftermath from the meadows: poor thin stuff. And the hard pocked surface of the gallops would knock delicate hooves to pieces. She would be far better off staying with Sophie and using Jack's unoccupied downs—such grass, second only to the Curragh of Kildare. This led on to the inadvisability of her riding at all while she was pregnant and to her reply 'My God, Maturin, how you do go on. Anyone would think I was a prize heifer. You are turning this baby into an infernal bore.'

He regretted their disagreements extremely, particularly since they had grown more—not so much more acrimonious or vehement as more spirited since their real marriage, their marriage in a church. During their former cohabitation they had quarrelled, of course; but very mildly—never a raised voice nor an oath, no broken furniture at all or even plates. Their marriage however had coincided with Stephen's giving up his long-established and habitual taking of opium, and although he was a physician it was only at this point that he fully realized what a very soothing effect his draught had had upon him, how very much it had calmed his body as well as his mind, a

nd what a shamefully inadequate husband it had made him, particularly for a woman like Diana. The change in his behaviour, the very decided change (for when undulled by laudanum he was of an ardent temperament) had added an almost entirely new and almost entirely beneficent depth to their connexion; and although it was in all likelihood the cause of the heat with which they now argued, each preserving an imperilled independence, it was quite certainly the cause of this baby. When Stephen had first heard that foetal heart beat, his own had stopped dead and then turned over. He was filled with a joy he had never known before, and with a kind of adoration for Diana.

The association of ideas led him to say, when they were half-way to the house, 'Jack, in my hurry I had almost forgot to tell you that I had two letters from Sam and two about him, all delivered from the same Lisbon packet. In both he sends you his most respectful and affectionate greetings—' Jack's face flushed with pleasure '—and I believe his affairs are in a most promising way.'

'I am delighted, delighted to hear it,' said Jack. 'He is a dear good boy.' Sam Panda, as tall as Aubrey and even broader, was Jack's natural son, as black as polished ebony yet absurdly recognizable—the same carriage, the same big man's gentleness, even the same features, transposed to another key. He had been brought up by Irish missionary priests in South Africa, and he was now in minor orders; he was unusually intelligent and from the merely temporal point of view he had a brilliant career before him, if only a dispensation would allow him to be ordained priest, for without one no bastard could advance much higher than an exorcist. Stephen had taken a great liking to him at their first meeting in the West Indies, and he had been using his influence in Rome and elsewhere. 'Indeed,' Stephen went on, his vexation of spirit diminishing as he spoke, 'I believe all that is needed now is the good word of the Patriarch, which I trust I may obtain when we touch at Lisbon.'

'Patriarch?' cried Jack, laughing loud. 'Is there really a Patriarch in Lisbon? A living Patriarch?'

'Of course there is a Patriarch. How do you suppose the Portuguese church could get along without a Patriarch? Even your quite recent sects find what they call bishops and indeed archbishops forsooth necessary. Every schoolboy knows that there are and always have been Patriarchs of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, the Indies, Venice, and, as I say, of Lisbon.'

'You astonish me, Stephen. I had always imagined that patriarchs were very, very old gentlemen in ancient times, with beards to their knees and long robes—Abraham, Methusalem, Anchises and so on. But you have Patriarchs actually walking about, ha, ha, ha!' He laughed with such good humour and amusement that it was impossible to preserve a sullen or dogged expression. 'Forgive me, Stephen. I am only an ignorant sailorman, you know, and mean no disrespect—Patriarchs, oh Lord!' They reached the gravel drive and with a graver look he said, but not nearly so loud, 'I am amazingly glad at what you tell me about Sam. He does so deserve to get on, with all his studying, his Latin and Greek and I dare say theology too—yet none of your bookworms neither—he must weigh a good seventeen stone and as strong as an ox. And his letters to me are so amiable and discreet—diplomatic, if you know what I mean. Anyone could read 'em. But, Stephen,' lowering his voice still farther as they walked up the steps, 'you need not mention it, unless you see fit, of course.'

Sophie had liked what she had seen of Sam, and although his relationship to her husband was obvious enough she had made no fuss of any kind: the begetting of Sam was indeed so long before her time that she scarcely had much ground for any sense of personal injury, and righteous indignation was not in her style; nevertheless Jack felt profoundly grateful to her. He also felt a corresponding degree of guilt when Sam was fresh in his mind; but these were not obsessive feelings by any means, and at present he was required to grapple with a completely different problem.

By the time he walked into the drawing-room with freshly powdered hair and a fine scarlet coat there was no remaining hint of guilt in his expression or his tone of voice. He glanced at the clock, saw that it would be at least five minutes before the arrival of his guests, and said, 'Ladies, I am sorry to tell you that our time ashore is cut short. We go aboard tomorrow and sail with the noonday tide.'

They all cried out at once, a shrill and discordant clamour of dissent—certainly he should not go—another six days had always been understood and laid down—how was it possible that their linen should be ready?—had he forgotten that Admiral Schank was to dine on Thursday?—it was the girls' birthday on the fourth: they would be so disappointed—how could he have overlooked his own daughters' birthday? Even Mrs Williams, his mother-in-law, whom poverty and age had quite suddenly reduced to a most pitiable figure, hesitant, fearful of giving offence or of not understanding, universally civil, painfully obsequious to Jack and Diana, almost unrecognizable to those who had known her in her strong shrewish confident talking prime, recovered something of her fire and declared that Mr Aubrey could not possibly fly off in that wild manner.

Stephen walked in, and Diana at once went over to him as he stood there in the doorway. Unlike Sophie she had dressed rather carelessly, partly because she was not pleased with her husband and partly because as she said 'women with great bellies had no business with finery'. She plucked his waistcoat straight and said, 'Stephen, is it true that you sail tomorrow?'

'With the blessing,' he said, looking a little doubtfully into her face.

She turned straight out of the room and could be heard running upstairs two at a time, like a boy.

'Heavens, Sophie, what a magnificent gown you are wearing, to be sure,' said Stephen.

'It is the first time I have put it on,' she replied, with a wan little smile and tears brimming in her eyes. 'It is the Lyons velvet you were so very kind as to . . .'

The guests arrived, Edward Smith, a shipmate of Jack's in three separate commissions and now captain of the Tremendous, 74, together with his pretty wife. Talk, much talk, the hearty talk of old friends, and in the midst of it Diana slipped in, blue silk from head to foot, the shade best calculated to set off the beauty of a woman with black hair, blue eyes, and an immense diamond, bluer still, hanging against her bosom. She had genuinely meant to make a discreet, unnoticed entrance, but conversation stopped dead, and Mrs Smith, a simple country lady who had been holding forth on jellies, gazed open-mouthed and mute at the Blue Peter pendant, which she had never seen before.

In a way this silence was just as well, for Killick, who acted as butler ashore, had recently been polished: he knew he must not jerk his thumb over his shoulder towards the dining-room in the sea-going way and say 'Wittles is up', but he was not yet quite sure of the right form: now, coming in just after Diana, he said in a low, hesitant tone that might not have been heard if there had been much of a din, 'Dinner-is on table sir which I mean ma'am if you please.'

A pretty good dinner in the English way, a dinner of two courses with five removes, but nothing to what Sophie would have ordered if she had known that this was to be Jack's last at home for an immense space of time. Yet at least the best port the cellar possessed had come up, and when the gorgeously-dressed women left them, the men settled down to it.

'When they are making good port wine, and the better kinds of claret and burgundy,' said Stephen, looking at the candle through his glass, 'men act like rational creatures. In almost all their other activities we see little but foolishness and chaos. Would not you say, sir, that the world was filled with chaos?'

'Indeed I should, sir,' said Captain Smith. 'Except in a well-run man-of-war, we see chaos all around us.'

'Chaos everywhere. Nothing could be simpler than carrying on a banking-house. You receive money, you write it down; you pay money out, you write it down; and the difference between the two sums is the customer's balance. But can I induce my bank to tell me my balance, answer my letters, attend to my instructions promptly? I cannot. When I go to expostulate I swim in chaos. The partner I wish to see is fishing for salmons in his native Tweed—papers have been mislaid—papers have not

come to hand—nobody in the house can read Portuguese or understand the Portuguese way of doing business—it would be better if I were to make an appointment in a fortnight's time. I do not say they are dishonest (though there is a fourpence for unexplained sundries that I do not much care for) but I do say they are incompetent, vainly struggling in an amorphous fog. Tell me, sir, do you know of any banker that really understands his business? Some modern Fugger?'

'Oh, Stephen, if you please,' cried Jack, for both Edward and Henry Smith, the sons of an Evangelical parson they much admired, were spoken of as Blue Lights in the Navy (prayers every day aboard and twice on Sunday), and although their fighting qualities took away from any sanctimonious implication the words might possess, it was known that they were very strict about coarse words, oaths and impropriety. Both brothers, Blue Lights or not, had been steadily kind and attentive to him in his recent disgrace, at considerable risk to their naval careers, and he did not wish his guest to be offended.

'I refer to the Fuggers, Mr Aubrey,' said Stephen, looking coldly at him. 'The Fuggers, I repeat, an eminent High Dutch family of bankers, the very type of those who understood their business, particularly in the time of Charles V.'

'Oh? I was not aware—perhaps I mistook your pronunciation. I beg pardon. But in any case Captain Smith is brother to the gentleman I told you about, the gentleman who is setting up a bank just at hand. That is to say another bank, for they have offices all over the county, and one in town of course. You know his other brother too, Henry Smith, who commands Revenge and who married Admiral Piggot's daughter: a thoroughly naval family. Poor Tom would have been a sailor too, but for his game leg. A most capital bank, I am sure; I am making some pretty considerable transfers, Tom Smith being so conveniently near. But as for your people, Stephen, I did not like to see young Robin lose fifteen thousand guineas in one session at Brooks's.'

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

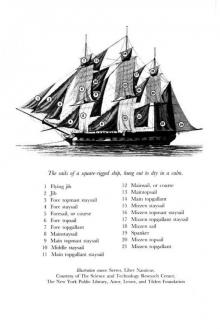

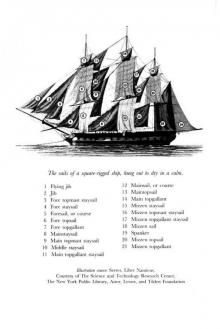

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea