- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

Master and Commander Page 2

Master and Commander Read online

Page 2

By the Right Honourable Lord Keith, Knight of the Bath, Admiral of the Blue and Commander in Chief of His Majesty's Ships and Vessels employed and to be employed in the Mediterranean, etc., etc., etc.

Whereas Captain Samuel Allen of His Majesty's Sloop Sophie is removed to the Pallas, Captain James Bradby deceased—

You are hereby required and directed to proceed on board the Sophie and take upon you the Charge and Command of Commander of her; willing and requiring all the Officers and Company belonging to the said Sloop to behave themselves in their several Employments with all due Respect and Obedience to you their Commander; and you likewise to observe as well the General Printed Instructions as what Orders and Directions you may from time to time receive from any your superior Officer for His Majesty's Service. Hereof nor you nor any of you may fail as you will answer the contrary at your Peril.

And for so doing this shall be your Order.

Given on board the Foudroyant

at sea, 1st April, 1800.

To John Aubrey, Esqr,

hereby appointed Commmander of

His Majesty's Sloop Sophie

By command of the Admiral Thos Walker

His eyes took in the whole of this in a single instant, yet his mind refused either to read or to believe it: his face went red, and with a curiously harsh, severe expression he obliged himself to spell through it line by line. The second reading ran faster and faster: and an immense delighted joy came welling up about his heart. His face grew redder still, and his mouth widened of itself. He laughed aloud and tapped the letter, folded it, unfolded it and read it with the closest attention, having entirely forgotten the beautiful phrasing of the middle paragraph. For an icy second the bottom of the new world that had sprung into immensely detailed life seemed to be about to drop out as his eyes focused upon the unlucky date. He held the letter up to the light, and there, as firm, comforting and immovable as the rock of Gibraltar, he saw the Admiralty's watermark, the eminently respectable anchor of hope.

He was unable to keep still. Pacing briskly up and down the room he put on his coat, threw it off again and uttered a series of disconnected remarks, chuckling as he did so. 'There I was, worrying . . . ha, ha . . . such a neat little brig—know her well . . . ha, ha . . . should have thought myself the happiest of men with the command of the sheer-hulk, or the Vulture slop-ship . . . any ship at all . . . admirable copperplate hand—singular fine paper . . . almost the only quarterdeck brig in the service: charming cabin, no doubt capital weather—so warm . . . ha, ha . . . if only I can get men: that's the great point . . .' He was exceedingly hungry and thirsty: he darted to the bell and pulled it violently, but before the rope had stopped quivering his head was out in the corridor and he was hailing the chambermaid. 'Mercy! Mercy! Oh, there you are, my dear. What can you bring me to eat, manger, mangiare? Pollo? Cold roast pollo? And a bottle of wine, vino—two bottles of vino. And Mercy, will you come and do something for me? I want you, désirer, to do something for me, eh? Sew on, cosare, a button.'

'Yes, Teniente,' said Mercedes, her eyes rolling in the candlelight and her teeth flashing white.

'Not teniente,' cried Jack, crushing the breath out of her plump, supple body. 'Capitan! Capitano, ha, ha, ha!'

He woke in the morning straight out of a deep, deep sleep: he was fully awake, and even before he opened his eyes he was brimming with the knowledge of his promotion.

'She is not quite a first-rate, of course,' he observed, 'but who on earth wants a blundering great first-rate, with not the slightest chance of an independent cruise? Where is she lying? Beyond the ordnance quay, in the next berth to the Rattler. I shall go down directly and have a look at her—waste not a minute. No, no. That would never do—must give them fair warning. No: the first thing I must do is to go and render thanks in the proper quarters and make an appointment with Allen—dear old Alien—I must wish him joy.'

The first thing he did in point of fact was to cross the road to the naval outfitter's and pledge his now elastic credit to the extent of a noble, heavy, massive epaulette, the mark of his present rank—a symbol which the shopman fixed upon his left shoulder at once and upon which they both gazed with great complacency in the long glass, the shopman looking from behind Jack's shoulder with unfeigned pleasure on his face.

As the door closed behind him Jack saw the man in the black coat on the other side of the road, near the coffee-house. The evening flooded back into his mind and he hurried across, calling out, 'Mr—Mr Maturin. Why, there you are, sir. I owe you a thousand apologies, I am afraid. I must have been a sad bore to you last night, and I hope you will forgive me. We sailors hear so little music—are so little used to genteel company—that we grow carried away. I beg your pardon.'

'My dear sir,' cried the man in the black coat, with an odd flush rising in his dead-white face, 'you had every reason to be carried away. I have never heard a better quartetto in my life—such unity, such fire. May I propose a cup of chocolate, or coffee? It would give me great pleasure.'

'You are very good, sir. I should like it of all things. To tell the truth, I was in such a hurry of spirits I forgot my breakfast. I have just been promoted,' he added, with an off-hand laugh.

'Have you indeed? I wish you joy of it with all my heart, sure. Pray walk in.'

At the sight of Mr Maturin the waiter waved his forefinger in that discouraging Mediterranean gesture of negation—an inverted pendulum. Maturin shrugged, said to Jack, 'The posts are wonderfully slow these days,' and to the waiter, speaking in the Catalan of the island, 'Bring us a pot of chocolate, Jep, furiously whipped, and some cream.'

'You speak the Spanish, sir?' said Jack, sitting down and flinging out the skirts of his coat to clear his sword in a wide gesture that filled the low room with blue. 'That must be a splendid thing, to speak the Spanish. I have often tried, and with French and Italian too; but it don't answer. They generally understand me, but when they say anything, they speak so quick I am thrown out. The fault is here, I dare say,' he observed, rapping his forehead. 'It was the same with Latin when I was a boy: and how old Pagan used to flog me.' He laughed so heartily at the recollection that the waiter with the chocolate laughed too, and said, 'Fine day, Captain, sir, fine day!'

'Prodigious fine day,' said Jack, gazing upon his rat-like visage with great benevolence. 'Bello soleil, indeed. But,' he added, bending down and peering out of the upper part of the window, 'it would not surprise me if the tramontana were to set in.' Turning to Mr Maturin he said, 'As soon as I was out of bed this morning I noticed that greenish look in the nor-nor-east, and I said to myself, "When the sea-breeze dies away, I should not be surprised if the tramontana were to set in."

'It is curious that you should find foreign languages difficult, sir,' said Mr Maturin, who had no views to offer on the weather, 'for it seems reasonable to suppose that a good ear for music would accompany a facility for acquiring—that the two would necessarily run together.'

'I am sure you are right, from a philosophical point of view,' said Jack. 'But there it is. Yet it may well be that my musical ear is not so very famous, neither; though indeed I love music dearly. Heaven knows I find it hard enough to pitch upon the true note, right in the middle.'

'You play, sir?'

'I scrape a little, sir. I torment a fiddle from time to time.'

'So do I! So do I! Whenever I have leisure, I make my attempts upon the 'cello.'

'A noble instrument,' said Jack, and they talked about Boccherini, bows and rosin, copyists, the care of strings, with great satisfaction in one another's company until a brutally ugly clock with a lyre-shaped pendulum struck the hour: Jack Aubrey emptied his cup and pushed back his chair. 'You will forgive me, I am sure. I have a whole round of official calls and an interview with my predecessor. But I hope I may count upon the honour, and may I say the pleasure—the great pleasure—of your company for dinner?'

'Most happy,' said Maturin, with a bow.

They were at the door. 'Then may we

appoint three o'clock at the Crown?' said Jack. 'We do not keep fashionable hours in the service, and I grow so devilish hungry and peevish by then that you will forgive me, I am sure. We will wet the swab, and when it is handsomely awash, why then perhaps we might try a little music, if that would not be disagreeable to you.'

'Did you see that hoopoe?' cried the man in the black coat.

'What is a hoopoe?' cried Jack, staring about.

'A bird. That cinnamon-coloured bird with barred wings. Upupa epops. There! There, over the roof. There! There!'

'Where? Where? How does it bear?'

'It has gone now. I had been hoping to see a hoopoe ever since I arrived. In the middle of the town! Happy Mahon, to have such denizens. But I beg your pardon. You were speaking of wetting a swab.'

'Oh, yes. It is a cant expression we have in the Navy. The swab is this'—patting his epaulette—'and when first we ship it, we wet it: that is to say, we drink a bottle or two of wine.'

'Indeed?' said Maturin with a civil inclination of his head. 'A decoration, a badge of rank, I make no doubt? A most elegant ornament, so it is, upon my soul. But, my dear sir, have you not forgot the other one?'

'Well,' said Jack, laughing, 'I dare say I shall put them both on, by and by. Now I will wish you a good day and thank you for the excellent chocolate. I am so happy that you saw your epop.'

The first call Jack had to pay was to the senior captain, the naval commandant of Port Mahon. Captain Harte lived in a big rambling house belonging to one Martinez, a Spanish merchant, and he had an official set of rooms on the far side of the patio. As Jack crossed the open spaces he heard the sound of a harp, deadened to a tinkle by the shutters—they were drawn already against the mounting sun, and already geckoes were hurrying about on the sunlit walls.

Captain Harte was a little man, with a certain resemblance to Lord St. Vincent, a resemblance that he did his best to increase by stooping, by being savagely rude to his subordinates and by the practice of Whiggery: whether he disliked Jack because Jack was tall and he was short, or whether he suspected him of carrying on an intrigue with his wife, it was all one—there was a strong antipathy between them, and it was of long standing. His first words were, 'Well, Mr Aubrey, and where the devil have you been? I expected you yesterday afternoon—Allen expected you yesterday afternoon. I was astonished to learn that he had never seen you at all. I wish you joy, of course,' he said without a smile, 'but upon my word you have an odd notion of taking over a command. Allen must be twenty leagues away by now, and every real sailorman in the Sophie with him, no doubt, to say nothing of his officers. And as for all the books, vouchers, dockets, and so on, we have had to botch it up as best we could. Precious irregular. Uncommon irregular.'

'Pallas has sailed, sir?' cried Jack, aghast.

'Sailed at midnight, sir,' said Captain Harte, with a look of satisfaction. 'The exigencies of the service do not wait upon our pleasure, Mr Aubrey. And I have been obliged to make a draft of what he left for harbour duty.'

'I only heard last night—in fact this morning, between one and two.'

'Indeed? You astonish me. I am amazed. The letter certainly went off in good time. It is the people at your inn who are at fault, no doubt. There is no relying on your foreigner. I give you joy of your command, I am sure, but how you will ever take her to sea with no people to work her out of the harbour I must confess I do not know. Allen took his lieutenant, and his surgeon, and all the promising midshipmen; and I certainly cannot give you a single man fit to set one foot in front of another.'

'Well, sir,' said Jack, 'I suppose I must make the best of what I have.' It was understandable, of course: any officer who could would get out of a small, slow, old brig into a lucky frigate like the Pallas. And by immemorial custom a captain changing ships might take his coxswain and boat's crew as well as certain followers; and if he were not very closely watched he might commit enormities in stretching the definition of either class.

'I can let you have a chaplain,' said the commandant, turning the knife in the wound.

'Can he hand, reef and steer?' asked Jack, determined to show nothing. 'If not, I had rather be excused.'

'Good day to you, then, Mr Aubrey. I will send you your orders this afternoon.'

'Good day, sir. I hope Mrs Harte is at home. I must pay my respects and congratulate her—must thank her for the pleasure she gave us last night.'

'Was you at the Governor's then?' asked Captain Harte, who knew it perfectly well—whose dirty little trick had been based upon knowing it perfectly well. 'If you had not gone a-caterwauling you might have been aboard your own sloop, in an officer like manner. God strike me down, but it is a pretty state of affairs when a young fellow prefers the company of Italian fiddlers and eunuchs to taking possession of his own first command.'

The sun seemed a little less brilliant as Jack walked diagonally across the patio to pay his call on Mrs Harte; but it still struck precious warm through his coat, and he ran up the stairs with the charming unaccustomed weight jogging there on his left shoulder. A lieutenant he did not know and the stuffed midshipman of yesterday evening were there before him, for at Port Mahon it was very much the thing to pay a morning call on Mrs Harte; she was sitting by her harp, looking decorative and talking to the lieutenant, but when he came in she jumped up, gave him both hands and cried, 'Captain Aubrey, how happy I am to see you! Many, many congratulations. Come, we must wet the swab. Mr Parker, pray touch the bell.'

'I wish you joy, sir,' said the lieutenant, pleased at the mere sight of what he longed for so. The midshipman hovered, wondering whether he might speak in such august company and then, just as Mrs Harte was beginning the introductions, he roared out, 'Wish you joy, sir,' in a wavering bellow, and blushed.

'Mr Stapleton, third of the Guerrier,' said Mrs Harte, with a wave of her hand. 'And Mr Burnet, of the Isis. Carmen, bring some Madeira.' She was a fine dashing woman, and without being either pretty or beautiful she gave the impression of being both, mostly from the splendid way she carried her head. She despised her scrub of a husband, who truckled to her; and she had taken to music as a relief from him. But it did not seem that music was enough, for now she poured out a bumper and drank it off with a very practised air;

A little later Mr Stapleton took his leave, and then after five minutes of the weather—delightful, not too hot even at midday—heat tempered by the breeze—north wind a little trying—healthy, however—summer already—preferable to the cold and rain of an English April—warmth in general more agreeable than cold—she said, 'Mr Burnet, I wonder whether I might beg you to be very kind? I left my reticule at the Governor's.'

'How charmingly you played, Molly,' said Jack, when the door had closed.

'Jack, I am so happy you have a ship at last.'

'So am I. I don't think I have ever been so happy in my life. Yesterday I was so peevish and low in my spirits I could have hanged myself, and then I went back to the Crown and there was this letter. Ain't it charming?' They read it together in respectful silence.

'Answer the contrary at your peril,' repeated Mrs Harte. 'Jack, I do beg and pray you will not attempt to make prize of neutrals. That Ragusan bark poor Willoughby sent in has not been condemned, and the owners are to sue him.'

'Never fret, dear Molly,' said Jack. 'I shall not be taking any prizes for a great while, I do assure you. This letter was delayed—damned curious delay—and Allen has gone off with all my prime hands; ordered to sea in a tearing hurry before I could see him. And the commandant has made hay of what was left for harbour duty: not a man to spare. We can't work out of harbour, it seems; so I dare say we shall ground upon our own beef-bones before ever we see so much as the smell of a prize.'

'Oh, indeed?' cried Mrs Harte, her colour rising: and at that moment in walked Lady Warren and her brother, a captain in the Marines. 'Dearest Anne,' cried Molly Harte, 'come here at once and help me remedy a very shocking injustice. Here is Captain Aubrey—you know one another?'

'Servant, ma'am,' said Jack, making a particularly deferential leg, for this was an admiral's wife, no less.

'—a most gallant, deserving officer, a thorough-paced Tory, General Aubrey's son, and he is being most abominably used . . .'

The heat had increased while he was in the house, and when he came out into the Street the air was hot on his face, almost like another element; yet it was not at all choking, not at all sultry, and there was a brilliance in it that took away all oppression. After a couple of turns he reached the tree-lined street that carried the Ciudadela road down to the high-perched square, or rather terrace, that overlooked the quays. He crossed to the shady side, where English houses with sash windows, fanlights and cobbled forecourts stood on unexpectedly good terms with their neighbours, the baroque Jesuit church and the withdrawn Spanish mansions with great stone coats of arms over their doorways.

A party of seamen went by on the other side, some wearing broad striped trousers, some plain sailcloth; some had fine red waistcoats and some ordinary blue jackets; some wore tarpaulin hats, in spite of the heat, some broad straws, and some spotted handkerchiefs tied over their heads; but they all of them had long swinging pigtails and they all had the indefinable air of man-of-war's men. They were Bellerophons, and he looked at them hungrily as they padded by, laughing and roaring out mildly to their friends, English and Spanish. He was approaching the square, and through the fresh green of the very young leaves he could see the Généreux's royals and topgallants twinkling in the sun far over on the other side of the harbour, hanging out to dry. The busy street, the green, and the blue sky over it was enough to make any man's heart rise like a lark, and three-quarters of Jack's soared high. But the remaining part was earthbound, thinking anxiously about his crew. He had been familiar with this nightmare of manning since his earliest days in the Navy, and his first serious wound had been inflicted by a woman in Deal with a flat-iron who thought her man should not be pressed; but he had not expected to meet it quite so early in his command, nor in this form, nor in the Mediterranean.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

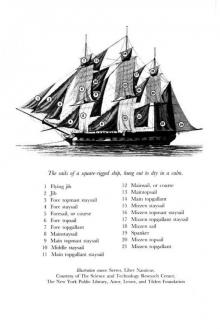

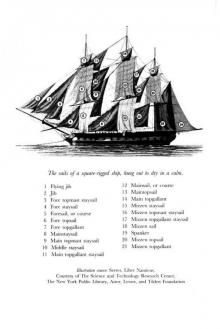

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea