- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Reverse of the Medal Page 2

The Reverse of the Medal Read online

Page 2

'He's telling the bumboats to go and—themselves,' said Harris.

'Yes, but it's cruel hard for a young foremast jack as has been longing for it watch after watch,' observed Bonden, a goatish man, quite unlike his brother.

'Never you fret your heart about the young foremast jack, Bob Bonden,' said Harris. 'He will get what he wants as soon as he goes ashore. And at any rate he knew he was shipping with a taut skipper.'

'The taut skipper is going to get a surprise,' said Reuben Wilks, the lady of the gun-room, and he laughed, deeply though kindly amused.

'Along of the black parson?' said Bonden.

'The black parson will bring him up with a round turn, ha, ha,' said Wilks; and another man said 'Well, well, we are all human,' in the same tolerant, amiable tone. 'We all have our little misfortunes.'

'So that is Captain Aubrey,' said Mrs Goole, looking across the water. 'I had no idea he was so big. Pray, Mr Richardson, why is he calling out? Why is he sending the boats back?' The lady's parents had only recently married her to Captain Goole; they had told her that she would have a pension of ninety pounds a year if he was knocked on the head, but otherwise she knew very little about the Navy; and, having come out to the West Indies in a merchantman, nothing at all about this naval custom, for merchantmen had no time for such extravagances.

'Why, ma'am,' said Richardson, with a blush, 'because they are filled with—how shall I put it? With ladies of pleasure.'

'But there are hundreds of them.'

'Yes, ma'am. There are usually one or two for every man.'

'Dear me,' said Mrs Goole, considering. 'And so Captain Aubrey disapproves of them. Is he very rigid and severe?'

'Well, he thinks they are bad for discipline; and he disapproves of them for the midshipmen, particularly for the squcakers—I mean the little fellows.'

'Do you mean that these—that these creatures could he allowed to corrupt mere boys?' cried Mrs Goole. 'Boys that their families have placed under the captain's particular care?'

'I believe it sometimes happens, ma'am,' said Richardson; and when Mrs Goole said 'I am sure Captain Goole would never allow it,' he returned no more than a civil, non-committal bow.

'So that is the fire-eating Captain Aubrey,' said Mr Waters, the flagship's surgeon, standing at the lee-rail of the quarterdeck with the Admiral's secretary. 'Well, I am glad to have seen him. But to tell you the truth I had rather see his medico.'

'Dr Maturin?'

'Yes, sir. Dr Stephen Maturin, whose book on the diseases of seamen I showed you. I have a case that troubles me exceedingly, and I should like his opinion. You do not see him in the boat, I suppose?'

'I am not acquainted with the gentleman,' said Mr Stone, 'but I know he is much given to natural philosophy, and conceivably that is he, leaning over the back of the boat, with his face almost touching the water. I too should like to meet him.'

They both levelled their glasses, focusing them upon a small spare man on the far side of the coxswain. He had been called to order by his captain and now he was sitting up, settling his scrub wig on his head. He wore a plain blue coat, and as he glanced at the flagship before putting on his blue spectacles they noticed his curiously pale eyes. They both stared intently, the surgeon because he had a tumour in the side of his belly and because he most passionately longed for someone to tell him authoritatively that it was not malignant. Dr Maturin would answer perfectly: he was a physician with a high professional reputation, a man who preferred a life at sea, with all the possibilities it offered to a naturalist, to a lucrative practice in London or Dublin—or Barcelona, for that matter, since he was Catalan on his mother's side. Mr Stone was not so personally concerned, but even so he too studied Dr Maturin with close attention: as the Admiral's secretary he attended to all the squadron's confidential business, and he was aware that Dr Maturin was also an intelligence agent, though on a grander scale. Stone's work was mainly confined to the detection and frustration of small local betrayals and evasions of the laws against trading with the enemy, but it had brought him acquainted with members of other organizations having to do with secret service, not all of them discreet, and from these he gathered that some kind of silent, hidden war was slowly reaching its climax in Whitehall, that Sir Joseph Blaine, the head of naval intelligence, and his chief supporters, among whom Maturin might be numbered, were soon to overcome their unnamed opponents or be overcome by them. Stone loved intelligence work; he very much hoped to become a full member of one of the many bodies, naval, military and political, that operated behind the scenes with what secrecy they could manage in spite of the indiscretion, not to say the incurable loquacity of certain colleagues; and he therefore stared with intense curiosity at a man who was, according to his fragmentary, imprecise information, one of the Admiralty's most valued agents—stared until the quarterdeck filled with ceremonial Marines and the sound of bosun's pipes and the first lieutenant said 'Come, gentlemen, if you please. We must receive the Captain of Surprise.'

'The Captain of Surprise, sir, if you please,' said the secretary at the cabin door.

'Aubrey, I am delighted to see you,' cried the Admiral, striking a last chord and holding out his hand. 'Sit down and tell me how you have been doing. But first, what is that ship you are towing?'

'One of our whalers, sir, the William Enderby of London, recaptured off Bahia. She rolled her masts out in a dead calm just north of the line, she being so deep-laden and the swell so uncommon heavy.'

'Recaptured, so a lawful prize. And deep-laden, eh?'

'Yes, sir. The Americans put the catch of three other ships into her, burnt them and sent her home alone. The master of Surprise, who was a whaler in his time, reckons her at ninety-seven thousand dollars. A sad time we have had with her, both of us being so precious short of stores. We did rig jury-masts made out of various bits and pieces and made fast with our shoe-strings, but she lost them in last Sunday's blow.'

'Never mind,' said the Admiral, 'you have brought her in, and that is the main thing. Ninety-seven thousand dollars, ha, ha! You shall have everything you need in the way of stores: I shall give particular orders myself. Now give me some account of your voyage. Just the essentials to begin with.'

'Very good, sir. I was unable to come up with the Norfolk in the Atlantic as I had hoped, but south of Falkland's Islands I did at least recapture the packet she had taken, the Danaë . . .'

'I know you did. Your volunteer commander—what was his name?'

'Pullings, sir. Thomas Pullings.'

'Yes, Captain Pullings—brought her in for wood and water before carrying her home. He was in Plymouth before the end of the month—having been chased like smoke and oakum for three days and nights by a heavy privateer—an amazing rapid passage. But tell me, Aubrey, I heard there were two chests of gold aboard that packet, each as much as two men could lift. I suppose you did not recapture them too?'

'Oh dear me no, sir. The Americans had transferred every last penny to the Norfolk within an hour of taking her. We did recover some confidential papers, however.'

At this point there was a silence, a silence that Captain Aubrey found exceedingly disagreeable. An untoward fall, the bursting open of a hidden brass box, had shown him that these papers were in fact money, a perfectly enormous sum of money, though in a less obvious form than coin; but this was unofficial knowledge, acquired only by accident, in his capacity as Maturin's friend, not his captain; and the real custodian of it was Stephen, whose superiors in the intelligence service had told him where to find the box and what to do with it. They had not told him why it was there, but no very great penetration was required to see that a sum of such extraordinary magnitude, in such an anonymous and negotiable form, must be intended for the subversion of a government at least. It was clearly something that Captain Aubrey could not speak about openly except in the improbable event of the Admiral's having been informed and of his giving a lead; but Jack hated this concealment—there was something sly, shifty and mean about it, to

gether with an edge of very dangerous dishonesty—and he found the silence more and more oppressive until he saw that in fact it was caused by Sir William's private conversion of ninety-seven thousand dollars into pounds and his division of the answer by twelve: this with a piece of black pencil on the corner of a dispatch. 'Forgive me for a moment,' said the Admiral, looking up from his sum with a cheerful face. 'I must pump ship.'

The Admiral vanished into the quarter-gallery, and as Jack Aubrey waited he recalled the conversation he had had with Stephen while the Surprise was running in. By nature and profession Stephen was exceedingly close; they had never spoken about these bonds, obligations, bank-notes and so on until it became obvious that Jack would be summoned aboard the flagship in the next few hours, but then in the privacy of the frigate's stern-gallery, he said, 'Everyone has heard the couplet

in vain may heroes fight and patriots rave

If secret gold sap on from knave to knave

but how many know how it goes on?'

'Not I, for one,' said Jack, laughing heartily.

'Will I tell you, so?'

'Pray do,' said Jack.

Stephen held up a watch-bill by way of symbol, and with a significant look he continued,

'Blest paper credit! last and best supply!

That lends corruption lighter wings to fly!

A single leaf shall waft an army o'er

Or ship off senates to a distant shore.

Pregnant with thousands flits the scrap unseen

And silent sells a king, or buys a queen.'

'I wish someone would try to corrupt me,' said Jack. 'When I think of how my account with Hoares must stand at the present moment, I would ship any number of senates to a distant shore for five hundred pounds; and for another ten the whole board of Admiralty too.'

'I dare say you would,' said Stephen. 'But you take my meaning, do you not? Were I in your place I should glide over that unhappy brass box and its contents, with just a passing reference to certain confidential papers to salve your conscience. I will come with you, if I may, so that if the Admiral prove inquisitive, I may toss him off with a round turn.'

Jack looked at Stephen with affection: Dr Maturin could dash away in Latin and Greek, and as for modern languages, to Jack's certain knowledge he spoke half a dozen; yet he was quite incapable of mastering low English cant or slang or flash expressions, let alone the technical terms necessarily used aboard ship. Even now, he suspected, Stephen had difficulty with starboard and larboard.

'The less said about these things the better,' added Stephen. 'I wish . . .' But here he stopped. He did not go on to say that he wished he had never seen these papers, had never had anything to do with them; but that was the case. Money, though obviously essential on occasion, usually had a bad effect on intelligence—for his part he had never touched a Brummagem farthing for his services—and money in such exorbitant, unnatural amounts might be very bad indeed, endangering all those who came into contact with it.

'I don't know how it is, Aubrey,' said the Admiral, coming back, 'but I seem to piss every glass these days. Perhaps it is anno Domini, and nothing to be done about it, but perhaps it is something that one of these new pills can set right. I should like to consult your surgeon while Surprise is refitting. I hear he is an eminent hand—was called in to the Duke of Clarence. But that to one side: carry on with your account, Aubrey.'

'Well, sir, not finding the Norfolk in the Atlantic I followed her round into the South Sea. No luck at Juan Fernandez, but a little later I had word of her playing Old Harry among our whalers along the coast of Chile and Peru and among the Galapagos. So I proceeded north, retaking one of her prizes on the way, and reached the islands a little after she had left; but there again I had fairly certain intelligence that she was bound for the Marquesas, where her commander meant to establish a colony as well as snapping up the half dozen whalers we had fishing in those waters. So I bore away westward, and to cut a long story short, after some weeks of sweet sailing, when we were right in her track—saw her beef-barrels floating—we had a most unholy blow, scudding under bare poles day after day, that we survived and she did not. We found her wrecked on the coral-reef of an uncharted island well to the east of the Marquesas; and not to trouble you with details, sir, we took her surviving people prisoner and proceeded to the Horn with the utmost dispatch.'

'Well done, Aubrey, very well done indeed. No glory, nor no cash from the Norfolk, I am afraid, it being an act of God that dished her; but dished she is, which is the main point, and I dare say you will get head-money for your prisoners. And then of course there are these charming prizes. No: a very satisfactory cruise, upon the whole. I congratulate you. Let us drink a glass of bottled ale: it is my own.'

'Very willingly, sir. But there is something I should tell you about the prisoners. From the beginning the captain of the Norfolk behaved very strangely; in the first place he said the war was over . . .'

'That's fair enough. A legitimate ruse de guerre.'

'Yes, but there were other things, together with a want of candour that I could not understand until I learnt that he was trying, naturally enough, to protect part of his crew; some of his men were deserters from the Navy and some had taken part in the Hermione . . .'

'The Hermione!' cried the Admiral, his face growing pale and wicked at the mention of that unhappy frigate and the still unhappier mutiny, when her crew murdered their inhuman captain and most of his officers and handed the ship over to the enemy on the Spanish Main. 'I lost a young cousin there, Drogo Montague's boy. They broke his arm and then fairly hacked him to pieces, only thirteen and as promising a youngster as you could wish, the damned cowardly villains.'

'We had a certain amount of trouble with them, sir, the ship having been blown off for a while; and some were obliged to be knocked on the head.'

'That saves us the trouble of hanging them. But you have some left, I trust?'

'Oh yes, sir. They are in the whaler, and if they might be taken off quite soon I should esteem it a kindness. We have never a boat to bless ourselves with, apart from my gig, and our few Marines are fairly worn to the bone with guarding them watch and watch.'

'They shall be clapped up directly,' cried the Admiral, pealing on his bell. 'Oh it will do my heart good to see 'em dingle-dangle at the yardarm, the carrion dogs. Jason should be in tomorrow and with you that will give us just enough post-captains for a court-martial.'

Jack's heart sank. He loathed a court-martial: he loathed a hanging even more. He also wanted to get away as soon as he had completed his water and taken in stores enough to carry him home, and from the obvious paucity of senior officers off Bridgetown he had thought he might be able to sail in two days' time. But it was no good protesting. The secretary and the flag-lieutenant were both in the cabin; orders were flying; and now the Admiral's steward brought in the bottled ale.

It was intolerably fizzy as well as luke-warm, but once his orders were given the Admiral drank it down in great gulps, with evident pleasure; presently the savage expression faded from his grim old face. After a long pause in which the clump of Marines' boots could be heard, and the sound of boats shoving off, he said 'The last time I saw you, Aubrey, was when Dungannon gave us dinner in the Defiance, and afterwards we played that piece of Gluck's in D minor. I have hardly had any music since, apart from what I play for myself. They are a sad lot in the wardroom here: German flutes by the dozen and not a true note between 'em. Jew's harps are more their mark. And all the mids' voices broke long ago; in any case there's not one can tell a B from a bull's foot. I dare say it was much the same for you, in the South Sea?'

'No, sir, I was much luckier. My surgeon is a capital hand with a violoncello; we saw away together until all hours. And my chaplain has a very happy way of getting the hands to sing, particularly Arne and Handel. When I had Worcester in the Mediterranean some time ago he brought them to a most creditable version of the Messiah.'

'I wish I had heard it,' said the Admiral. H

e refilled Jack's glass and said, 'Your surgeon sounds a jewel.'

'He is my particular friend, sir: we have sailed together these ten years and more.'

The Admiral nodded. 'Then I should be happy if you would bring him this evening. We might take a hit of supper together and have a little music; and if he don't dislike it, I should like to consult him. Yet perhaps that might be improper; I know these physical gentlemen have a strict etiquette among themselves.'

'I believe your surgeon would have to give his consent, sir. They probably know one another, however, and it would be no more than a formality; Maturin is aboard at this moment, and if you wish I will speak to him before I pay my call on Captain Goole.'

'You are going to wait on Goole, are you?' asked Sir William.

'Oh yes, sir: he is senior to me by a good six months.'

'Well, do not forget to wish him joy. He was married a little while ago: you would have thought him safe enough, at his age, but he is married, and has his wife aboard.'

'Lord!' cried Jack. 'I had no idea. I shall certainly give him joy—and he has her aboard?'

'Yes, a meagre yellow little woman, come from Kingston for a few weeks to recover from a fever.'

Jack's heart and mind were so filled with thoughts of Sophie, his own wife, and with a boundless longing for her to be aboard that he missed the sense of the Admiral's words until he heard him say 'You will tip it the civil to them, Aubrey, when you run each of 'em to earth. These medicos are a stiff-necked, independent crew, and you must never cross them just before they dose you.'

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

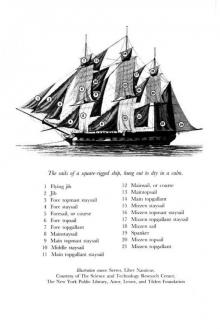

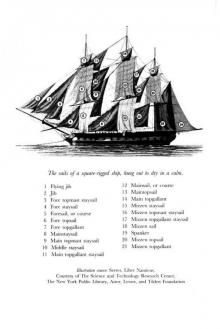

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea