- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Mauritius Command Page 17

The Mauritius Command Read online

Page 17

'Jack Aubrey. The lieutenant of long ago is still visible in the grave commodore, but there are times when he has to be looked for. One constant is that indubitable happy courage, the courage of the fabled lion—how I wish I may see a lion—which makes him go into action as some men might go to their marriage-bed. Every man would be a coward if he durst: it is true of most, I do believe, certainly of me, probably of Clonfert; but not of Jack Aubrey. Marriage has changed him, except in this: he had hoped for too much, poor sanguine creature (though indeed he is sick for news from home). And the weight of this new responsibility; he feels it extremely: responsibility and the years—his youth is going or indeed is gone. The change is evident, but it is difficult to name many particular alterations, apart from the comparative want of gaiety, of that appetence for mirth, of those infinitesimal jests that caused him at least such enormous merriment. I might mention his attitude towards those under his command, apart from those he has known for years: it is attentive, conscientious, and informed; but is far less personal; his mind rather than his heart is concerned, and the people are primarily instruments of war. And his attitude towards the ship itself: well do I remember his boundless delight in his first command, although the Sophie was a sad shabby little tub of a thing—the way he could not see enough of her meagre charms, bounding about the masts, the rigging, and the inner parts with an indefatigable zeal, like a great boy. Now he is the captain of a lordly two-decker, with these vast rooms and balconies, and he is little more than polite to her; she might be one set of furnished lodgings rather than another. Though here I may be mistaken: some aspects of the sailor's life I do not understand. Then again there is the diminution not only of his animal spirits but also of his appetites: I am no friend to adultery, which surely promises more than it can perform except in the article of destruction; but I could wish that Jack had at least some temptation to withstand. His more fiery emotions, except where war is concerned, have cooled; Clonfert, younger in this as in many other ways, has retained his capacity for the extremes of feeling, certainly the extremity of pain, perhaps that of delight. The loss is a natural process no doubt, and one that prevents a man from burning away altogether before his time; but I should be sorry if, in Jack Aubrey's case, it were to proceed so far as a general cool indifference; for then the man I have known and valued so long would be no more than the walking corpse of himself.'

The sound of the bosun's call, the clash of the Marines presenting arms, told him that Jack Aubrey's body, quick or dead, was at this moment walking about within a few yards of him. Stephen dusted sand upon his book, closed it, and waited for the door to open.

The officer who appeared did indeed resemble Commodore rather than Lieutenant Aubrey, even after he had flung his coat and with it the marks of rank on to a nearby locker. He was bloated with food and wine; his eyes were red and there were liverish circles under them; and he was obviously far too hot. But as well as the jaded look of a man who has been obliged to eat and drink far too much and then sit in an open carriage for twenty miles in a torrid dust-storm, wearing clothes calculated for the English Channel, his face had an expression of discouragement.

'Oh for some more soldiers like Keating,' he said wearily. 'I cannot get them to move. We had a council after dinner, and I represented to them, that with the regiments under their command we could take La Réunion out of hand: the Raisonable would serve as a troop-carrier. St Paul's is wide open, with not one stone of the batteries standing on another. They agreed, and groaned, and lamented—they could not move without an order from the Horse-Guards; it had always been understood that the necessary forces were to come from the Madras establishment, perhaps with the next monsoon if transports could be found; if not, with the monsoon after that. By the next monsoon, said I, La Réunion would be bristling with guns, whereas now the French had very few, and those few served by men with no appetite for a battle of any kind: by the next monsoon their spirits would have revived, and they would have been reinforced from the Mauritius. Very true, said the soldiers, wagging their heads; but they feared that the plan worked out by the staff must stand: should I like to go shooting warthogs with them on Saturday? And to crown all, the brig was not a packet but a merchantman from the Azores—no letters of any kind. We might as well be at the back of the moon.'

'It is very trying, indeed,' said Stephen. 'What say you to some barley-water, with lime-juice in it? And then a swim? We could take a boat to the island where the seals live.'

To a cooler, fresher Jack he offered what comfort he could provide. He left the stolid torpor of the soldiers to one side—neither had really believed in the possibility of stirring them, after the dismal end of the unauthorized expedition to Buenos Aires from this very station not many years before—and concentrated on the changed perception of time during periods of activity; these busy weeks had assumed an importance unjustified by their sidereal, or as he might say their absolute measure; with regard to exterior events they still remained mere weeks; it had been unreasonable to expect anything on their return to the Cape; but now a ship might come in any day at all, loaded with mail.

'I hope you are right, Stephen,' said Jack, balancing on the gunwale and rubbing the long blue wound on his back. 'Sophie has been very much in my mind these last few days, and even the children. I dreamt of her last night, a huddled, uneasy dream; and I long to hear from her.' After a considering pause he said, 'I did bring back some more pleasant news, however: the Admiral is fairly confident of being able to add Iphigenia and Magicienne to the squadron within the next few weeks; he had word from Sumatra. But of course they will be coming from the east—not the least possibility of anything from home. The old Leopard, too, though nobody wants her: iron sick throughout, a real graveyard ship.'

'The packet will come in from one day to the next, and it will bring a budget of tax-demands, bills, and an account of the usual domestic catastrophes: news of mumps, chicken-pox, a leaking tap; my prophetic soul sees it beneath the horizon.'

The days dropped by while the Boadicea, her holds emptied and herself heaved down with purchase to bollards on the shore, had her foul bottom cleaned; Jack set up his telescope with a new counterbalance that worked perfectly on land; Stephen saw his lion, a pride of lions; and then, although it had mistaken the horizon, his prophetic soul was shown to have been right: news did come in. But it was not domestic news, nor from the west: the flying Wasp had turned about in mid-ocean and had come racing back to the Cape to report that the French had taken three more Indiamen, HM sloop Victor, and the powerful Portuguese frigate Minerve.

The Vénus and the Manche, already at sea when the squadron looked into Port-Louis, had captured the Windham, the United Kingdom, and the Charlton, all Indiamen of the highest value. The Bellone, slipping out past the blockade by night, had taken the eighteen-gun Victor, and then she and her prize had set about the Minerva, which mounted fifty-two guns, but which mounted them in vain against the fury of the French attack. The Portuguese, now La Minerve, was at present in Port-Louis, manned by seamen from the Canonnière and some deserters: the Indiamen, the Vénus and the Manche were probably there too, but of that the Wasp was not quite sure.

Before the turn of the tide Jack was at sea, the wart-hogs, the soldiers, and even his telescope left behind: he had shifted his pennant into the Boadicea, for the hurricane months were not far away, and the Raisonable could not face them. He was back in his own Boadicea, driving her through variable and sometimes contrary winds until they reached the steady south-east trade, when she lay over with her lee-rail under white water, her deck sloping like the roof of Ashgrove Cottage, and began to tear off her two hundred and fifty and even three hundred nautical miles between one noon observation and the next; for there was some remote hope of catching the Frenchmen and their prizes, cutting them off before they reached Mauritius.

On the second Sunday after their departure, with church rigged, Jack was reading the Articles of War in a loud, official, comminatory voice by way of sermon an

d all hands were trying to keep upright (for not a sail might be attempted to be touched). He had just reached article XXIX, which dealt with sodomy by hanging the sodomite and which always made Spotted Dick and other midshipmen swell purple from suppressed giggling at every monthly repetition, when two ships heaved in sight. They were a great way off, and without interrupting her devotions, such as they might be with every mind fixed earnestly upon the mast-head, the Boadicea edged away to gain the weather-gage. But by the time Jack had reached All crimes not capital (there were precious few), and well before he cleared the ship for action, the windward stranger broke out the private signal. In answer to the Boadicea's she made her number: the Magicienne; and her companion was the Windham.

The Magicienne, said Captain Curtis, coming aboard the Commodore, had retaken the Indiamen off the east coast of Mauritius. The Windham had been separated from her captor, the Vénus, during a tremendous sudden blow in 17°S; the Magicienne had snapped her up after something of a chase, beating to windward all day, and had then stood on all night in the hope of finding the French frigate. Curtis had found her at sunset, looking like a scarecrow with only her lower masts standing and a few scraps of canvas aboard, far away right under the land, creeping in with her tattered forecourse alone. But unhappily the land to which she was creeping was the entrance to Grand-Port; and when the land-breeze set in, blowing straight in her teeth, the Magicienne had the mortification of seeing the Vénus towed right under the guns of the Ile de la Passe, at the entrance to the haven.

'By the next morning, sir, when I could stand in,' said Curtis apologetically, 'she was half way up to the far end, and with my ammunition so low—only eleven rounds to a gun—and the Indiaman in such a state, I did not think it right to follow her.'

'Certainly not,' said Jack, thinking of that long inlet, guarded by the strongly fortified Ile de la Passe, by batteries on either side and at the bottom and even more by a tricky, winding fairway fringed with reefs: the Navy called it Port South-East, as opposed to Port-Louis in the north-west, and he knew it well. 'Certainly not. It would have meant throwing the Magicienne away; and I need her. Oh, yes, indeed, I need her, now they have that thumping great Minerva. You will dine with me, Curtis? Then we must bear away for Port-Louis.' They passed the Indianian a tow, and lugging their heavy burden through the sea they stood on, the wind just abaft the beam.

Stephen Maturin had been deeply mistaken in supposing that Jack, older and more consequential, now looked upon ships as lodgings, more or less comfortable: the Raisonable had never been truly his; he was not wedded to her. The Boadicea was essentially different; he entered into her; he was one of her people. He knew them all, and with a few exceptions he liked them all: he was delighted to be back, and although Captain Eliot had been a perfectly unexceptionable officer, they were delighted to have him. They had in fact led Eliot a sad life of it, opposing an elastic but effective resistance to the slightest hint of change: 'The Commodore had always liked it this way; the Commodore had always liked it that; it was Captain Aubrey that had personally ordered the brass bow-chasers to be painted brown.' Jack particularly valued Mr Fellowes, his bosun, who had clung even more firmly than most to Captain Aubrey's sail-plan and his huge, ugly snatch-blocks that allowed hawsers to be instantly set up to the mastheads, there to withstand the strain of an extraordinary spread of canvas; and now that the Boadicea's hold had been thoroughly restowed, her hull careened, and her standing-rigging rerove with the spoils of St Paul's, she answered their joint hopes entirely. In spite of her heavy burden she was now making nine knots at every heave of the log.

'She is making a steady nine knots,' said Jack, coming below after quarters.

'How happy you make me, Jack,' said Stephen. 'And you might make me even happier, should you so wish, by giving me a hand with this. The unreasonable attitude, or lurch, of the ship caused me to overset the chest.'

'God help us,' cried Jack, gazing at the mass of gold coins lying in a deep curve along the leeward side of the cabin. 'What is this?'

'It is technically known as money,' said Stephen. 'And was you to help me pick it up, instead of leering upon it with a stunned concupiscence more worthy of Danae than a King's officer, we might conceivably save some few pieces before they all slip through the cracks in the floor. Come, come, bear a hand, there.'

They picked and shovelled busily, on all fours, and when the thick squat iron bound box was full again, Stephen said, 'They are to go into these small little bags, if you please, by fifties: each to be tied with string. Will I tell you what it is, Jack?' he said, as the heavy bags piled up.

'If you please.'

'It is the vile corrupting British gold that Buonaparte and his newspapers do so perpetually call out against. Sometimes it exists, as you perceive. And, I may tell you, every louis, every napoleon, every ducat or doubloon is sound: the French sometimes buy services or intelligence with false coin or paper. That is the kind of thing that gives espionage a bad name.'

'If we pay real money, it is to be presumed we get better intelligence?' said Jack.

'Why, truly, it is much of a muchness: your paid agent and his information are rarely of much consequence. The real jewel, unpurchasable, beyond all price, is the man who hates tyranny as bitterly as I do: in this case the royalist or the true republican who will risk his life to bring down that Buonaparte. There are several of them on La Réunion, and I have every reason to believe there are more on the Mauritius. As for your common venal agents,' said Stephen, shrugging, 'most of these bags are for them; it may do some good; indeed it probably will, men rarely being all of a piece. Tell me, when shall you be able to set me down? And how do you reckon the odds at present?'

'As to the first,' said Jack, 'I cannot say until I have believe they are looked into Port-Louis. The odds? I still about evens for the moment. If they have gained the Minerve, we have gained the Magicienne. You will tell me that the Minerve is the heaviest of the two, and that the Magicienne only carries twelve-pounders; but Lucius Curtis is a rare plucked 'un, a damned good seaman. So let us say evens for the moment. For the moment, I say, because the hurricane-season is coming, and if they lie snug in port and we outside, why, there is no telling how we shall stand in a few weeks' time.'

During the night they brought the wind aft as they went north about Mauritius, and when Stephen woke he found the Boadicea on an even keel; she was pitching gently, and the urgent music that had filled her between decks these last days was no longer to be heard. He washed his face perfunctorily, passed his hand over his beard, said 'It will do for today,' and hurried into the day-cabin, eager for coffee and his first little paper cigar of the day. Killick was there, gaping out of the stern-window, with the coffee-pot in his hand.

'Good morning, Killick,' said Stephen. 'Where's himself?'

'Good morning, sir,' said Killick. 'Which he's still on deck.'

'Killick,' said Stephen, 'what's amiss? Have you seen the ghost in the bread-room? Are you sick? Show me your tongue.'

When Killick had withdrawn his tongue, a flannelly object of inordinate length, he said, paler still, 'Is there a ghost in the bread-room, sir? Oh, oh, and I was there in the middle watch. Oh, sir, I might a seen it.'

'There is always a ghost in the bread-room. Light along that pot, will you now?'

'I durs'nt, sir, begging your pardon. There's worse news than the ghost, even. Them wicked old rats got at the coffee, sir, and I doubt there's another pot in the barky.'

'Preserved Killick, pass me that pot, or you will join the ghost in the bread room, and howl for evermore.'

With extreme unwillingness Killick put the pot on the very edge of the table, muttering, 'Oh, I'll cop it: oh, I'll cop It.'

Jack walked in, poured himself a cup as he bade Stephen good morning, and said, 'I am afraid they are all in.'

'All in what?'

'All the Frenchmen are in harbour, with their two Indiamen and the Victor. Have not you been on deck? We are lying off Port-Louis. The coffee has a

damned odd taste.'

'This I attribute to the excrement of rats. Rats have eaten our entire stock; and I take the present brew to be a mixture of the scrapings at the bottom of the sack.'

'I thought it had a familiar tang,' said Jack. 'Killick, you may tell Mr Seymour, with my compliments, that you are to have a boat. And if you don't find at least a stone of beans among the squadron, you need not come back. It is no use trying Néréide; she don't drink any.'

When the pot had been jealously divided down to its ultimate dregs, dregs that might have been called dubious, had there been the least doubt of their nature, they went on deck. The Boadicea was lying in a splendid bay, with the rest of the squadron ahead and astern of her: Sirius, Néréide, Otter, the brig Grappler which they had retaken at St Paul's, and a couple of fore-and-aft-rigged avisoes, from the same source: to leeward the Windham Indiaman, with parties from each ship repairing the damage caused by the blow and the violence of the enemy, watched by the philosophical French prize-crew. At the bottom of the deep curve lay Port-Louis, the capital of Mauritius, with green hills rising behind and cloud-capped mountains beyond them.

'Shall you adventure to the maintop?' asked Jack. 'I could show you better from up there.'

'Certainly,' said Stephen. 'To the ultimate crosstrees, if you choose: I too am as nimble as an ape.'

Jack was moved to ask whether there were earthbound apes, as compact as lead, afflicted with vertigo, possessed of two left hands and no sense of balance; but he had seen the startling effect of a challenge upon his friend, and apart from grunting as he thrust Stephen up through the lubber's hole, he remained silent until they were comfortably installed among the studding sails, with their glasses trained upon the town.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

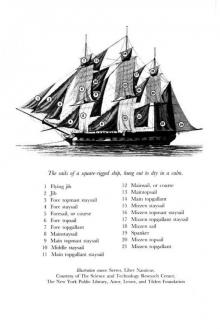

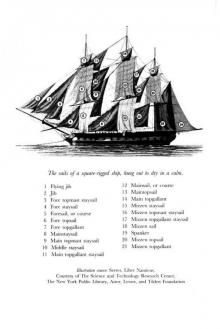

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea