- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Page 17

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Read online

Page 17

Before Peleg had fallen a yard the fiends of hell were upon Kevin and they snatched him away to their own place, he screaming like a stuck pig about their oath and they laughing white-hot tongues of fire.

And the angel at the bottom of the chasm peered up through the shifting fog and altered his feet, and as he caught Peleg he said, ‘There, easy now, Peleg.’ And he put him down and looked kindly in his face and said, ‘Sit down upon the flat rock, Peleg, for you are pale in the face, I find.’ ‘God put a flower on you, joy,’ said Peleg, and thanked him with all the civility at his command and many elegant turns of speech.

The angel let him breathe awhile and said, ‘Stand up now, Peleg, for I have a message for you. It is you must go down to the sea again, to the heathen of the pagan shore, and there are fourteen kings of the pagan shore to whom you must preach the faith, for now there is virtue in you. That is the message: and now we shall take a glass or two together, for I have a bottle conveniently near at hand, and it appears that I will not see you again until I stand with my trumpet to sound you in over the mossy walls of Paradise.’

A Passage of the Frontier

THE THREAT from the north grew stronger, and the stateless persons and undesirables began to move towards the Mediterranean and the southern frontiers. Then suddenly, overnight, the full danger was there, immediately at hand: blind tanks roared down the motorways, endless lines of trucks full of infantrymen, guns, the political police; and far ahead of them all parachutists were setting up roadblocks, directing the military traffic, requisitioning houses, carrying out the first arrests. All trains were stopped, all main roads, bridges, tunnels closed.

Now plans that needed more than a few hours for their execution were abandoned; now the nearest road was the only road; and before dawn on Friday a hired car put Martin down at the end of a charcoal-burner’s track on the high slope of the Coma du Loup.

They would have preferred to get him out of the country by way of Switzerland, but that was impossible now: all frontiers were closed to those with no legal identity. Encantats was the only solution, a small Pyrenean smuggling centre inland from Andorra, even higher and more remote. It possessed no motor-road into France, but as even the mule-track was guarded they had him set down in the Coma du Loup with a drawing of the smugglers’ path and a carrier-bag of food; and Jacob lent him a hard-weather coat. The driver also had an envelope of paper money, to be handed over at the last moment; but he did not see fit to hand it over – he turned his car, throwing up loose earth, bark and scraps of charcoal on the blackened ground. Martin made stiff, inadequate gestures to guide him – stiff because he was still cramped by the long night’s headlong flight. The driver took no notice until the car was round; then he put his huge face out of the window, and through the smoke and steam he shouted, ‘You follow the river. The ford is the boundary. Cross and follow the right-hand stream. You can’t miss it.’

‘Thank you very much,’ said Martin. ‘Good-bye.’

‘The stream on the right,’ said the driver, holding up his left hand. ‘I’ve never been there myself, but you can’t miss it.’ He gave Martin a cold nod, crashed the gear home and jerked off down the track. The car was gone in a moment, but for some time it could still be heard, winding down through the trees in the darkness. Martin did not move until the sudden chatter of a jay startled him into motion, breaking a spell that might have lasted until the rising of the sun. He picked up his paper bag and began to climb through the trees.

This was near the top of the forest: he had passed up through the last half-mile of beeches, and now on the higher slope it was all pines, scaley pines standing steep from the mountainside. On his right hand the broad stream ran fast and deep, fall and pool, fall and pool all the way, and the brown water racing between high banks of rock.

At the beginning, under the beeches, there had been a clear path, indeed several paths; but up here the pine-needles did not hold the track. There were great heaps made by ants with wandering lines among them that might have been made by any number of beasts; but nothing like a distinct trail. The slope increased, and soon he was gasping; and as the day grew warmer, so green clouds of pollen began to drift through the forest, an enormous vegetable act of love. He came to a rocky shoulder where the trees grew sparse – no canopy to shut him in – and far over he saw the opposing mountain-flank, smoking green as though the whole forest were on fire.

In another hour he reached a level stretch of the river, a place where he could reach the water and wash and drink at last. Drying, he sat on a grey boulder and picked raspberries. They grew all along among the rounded boulders, now that the trees were thinner, together with columbines and yellow lilies. Out there in the stream, where a fallen trunk had made an island, stood another lily, a tall purple spotted one whose petals curved back to touch its stem; and lying among the leaves at its foot, a blue crumpled packet that had held cigarettes. Nearer, in the gin-clear water, a rusting sardine-tin. ‘Might this be the ford?’ he said, and looked more attentively at the banks. Yes, certainly this was a place where one could cross, perhaps the first he had seen between the deep-cut banks; and certainly people had been crossing here for years and years, since the steep rock on the far bank was worn into steps. And farther up another stream joined this, as both the drawing and the driver had said.

So this was the frontier itself. He stepped into the water, unbelievably cold, and stood for a while with a foot on either side of the middle-line: then he waded over, to another country.

It feels much the same, however, he said, looking back to the bank he had left. The same trees over there, the same wild falls of rock, furred over with dry grey lichen; and a very small bird continually flitted to and fro across the water, busily from tree to tree, minding him no more than if he had been a cow.

Where it ran along the difficult course of the right-hand stream, the path was clear again; and often whole stretches of the bare mother-rock were trodden out into a smoothness that showed the grain and inner colour of the schist; but sometimes the steady upward sweep of the mountain was broken by broad level steps where the river soaked promiscuously among the bushes and the swampy earth, the coarse hummocks of grass and sour brown pools; here, and even more in the frequent steep gulleys, the path would divide, wander and dwindle into unmeaning ribbons. Yet time and again when he seemed to have lost it for ever his hand would reach out for a branch whose bark was already worn to the wood, or as he leapt a small ravine his foot would land in a place worn deep by other men. The path always reappeared, and it led him high, high towards the last thinning-out of the trees; now they stood wide apart, each one lower, with its under-branches touching the now frosty ground, and each looking older by far. The whole character of the forest had changed; the trees no longer hemmed him in, but stood casually, with junipers between them and even broad glades of low pink-flowering rhododendrons or open grass, studded with unopened gentians.

Then came one last belt of ancient twisted moss-clad pines, hardly more than bushes, and abruptly he was out of the trees altogether: they were ruled off as though by a line, and the sky, no longer patches of light above the branches, spread wide overhead. An enormous sky; vivid and brilliant beyond anything he had imagined: these hours of climbing had kept his head down, and now the immensity of this vast bowl overwhelmed him.

Another five hundred feet over the bare grass and he sat down to gaze round the world. His heart was pounding and his breath came short – visible breath that lingered in the unmoving, frigid air – and for some time his gasping body would scarcely let him comprehend what he saw: it was as though he were contemplating a brilliant but entirely foreign universe. Yet in time it resumed an intelligible form: there was his dark forest, sweeping down in wave after wave to the dim lower clouds; and beyond the great valley to the north rose answering mountains with rounded tops. Somewhere in the hidden land between them must be the last remote village and the road. It was an enormous landscape, on a scale that quite abolished hours or miles,

but this was not the half of it – behind him the high mountain cut off the rest of the world. To his right as he turned there were two soaring peaks, joined by a ragged curtain-wall; they were very dark on this northward side, and the snow that lay in their deep gulleys showed with a deathly light; they had screes and beds of shale hanging on their steep sides or running down to the chaotic rocks below, and the screes were cold and grey, severely inanimate. But on his left the solitary peak had caught the sun. Every detail of its warm brown and ochre cliffs was clear, and in this brilliant clarity it might have been no more than an hour away, but for the golden cloud that floated between him and the nearest spur. Between these mountains, and due south of him, there appeared the upward edge of a wilderness of rock that threw up uncounted peaks; their grey northern sides were powdered with snow, and deep snow lay here and there in streaks. These raised, distant peaks were all he could see of the waste beyond. ‘The necessary pass will be clear, no doubt,’ he said, ‘once I can survey the whole.’

The cold seeped into him from below; the air bit his ears and nose; and when at last he felt for the map his hands were numb. The single mountain was certainly Malamort, and it was beyond it, on the sunward side, that he must go, through a gap between the mountain and the chaos to the south: he could see no gap, but his drawing showed the path, a line winding up to the shoulder of Malamort. The gap must be there, and it must be exactly to the south-east, hidden by some nearer crest. With a sudden eager desire to know what was on the other side of the limiting ridge, to find the pass, to be moving in this silent enormous world, he started up the slope, a smooth alp dotted with pale boulders like gigantic sheep.

It was a rounded slope whose skyline mounted pace by pace with him, false crests in an interminable series, and it was steep; yet he hurried up it, sometimes chuckling, sometimes singing loud; and where the slope was less he ran in bounds, waving his arms and singing louder still. The grass thinned and the bare earth showed more as he gained height, gritty earth among pale grass, dirty and crushed from the snow that had left it a few days ago. Now and then he slipped and fell; but he fell easy on the wet sloping ground; it did not affect his elation nor his speed and in time he gained the true ridge at last, with its long wave of standing snow. Here he fell silent: now he was standing in the sun, astride of a vaster world by far, because the last two thousand feet had brought up mountains on every hand, and he was above them all, above everything except Malamort; and clean round the horizon these mountains rose and fell, a brown infinity. The great valley on the north was gone, obliterated by the miracle of breeding cloud, rounded white masses rising below him into the middle air, forming slow whirlpools and momentary towers. Once the whole gleaming ocean parted from top to bottom, and he saw a heightened fragment of the common world – thread-like roads, the railway-line, a winding river, the huddle of a town with smoke, the minute patchwork of fields. But with the closing of the clouds and their continual mounting there was nothing on that side but the great ranges as they stretched away, illimitable against the lower sky, rising from the rising sea of white: but on this side, the new, southern, sunlit side, no clouds; nothing but a desert of broken rock, brilliantly lit yet dark and even black in places, with sheets of snow and many lakes, black-rimmed, shining water in the hollows; screes everywhere, and rarely a touch of green. The wilderness filled all the middle distance, and beyond it the saw-edged ranges ran on and on: the mountains of Aragon, no doubt, and perhaps those of Navarre.

The snow under his feet was crusted, granular and hard; it was pocked with old rain and powdered with a dust of earth, but beneath the crust it was the purest white. Its taste was thin – insubstantial – yet it left a burning in his mouth.

Virgin snow: there seemed a want of piety in walking upon its unbroken smoothness; and never was there such a world for piety – it might have been created yesterday. Others had not felt the same, however. Twenty yards away to the left footmarks crossed it at its lowest point. What is more, they continued beyond the present limit of the snow; and these compressed footprints were still unmelted; they ran on, a series of white dots pointing straight to a cleft under the sheer rock-face of Malamort, a slit perhaps an hour away, hardly to be seen at all in the blaze of the sun without their help. For this necessary pass, this Portal Nera, lay in the deep shadow among black, impassable rocks.

Once he was across and fairly on the southern slope, the sun warmed him through and through, comforting him to the bone. The gentians were open here, stars and trumpets, fields of them, and the air was like good news: he said, I could go on for ever.

He walked with long, reaching strides, on and on: yet the sun climbed and the pass barely moved. The air was stirring now, and a black vulture rose in spirals on a thermal current until it was no bigger than a lark: the bowl of the sky turned an even intenser blue. This was perfect walking, these miles of level or slightly downward path, almost like a slow gentle flight or even levitation after the grind of the ascent: slowly the pass changed shape, and to his left the peak soared higher still, growing until it filled the eastern quarter of the sky.

For long stretches he watched the alternate reappearance of his feet and the even flow of the ground beneath. Once he looked up at the clatter of a band of chamois crossing a scree a mile away to the west, and once he followed the flight of a large white butterfly with red eye-spots on its wings; but upon the whole he kept his head down, in a floating dream.

The third time he looked up he was in the very entrance of the pass, and he saw a man in a grey cloth cap, a surly red-eyed man with his legs wrapped in coarse brown paper from knee to ankle: he was sitting on a dark boulder in the shadow of the cliff, beside a shapeless load, or burden. He asked Martin had he the right time?

‘I am afraid I have not,’ said Martin, ‘but it is early yet, I am sure.’ He sat down and watched the man as he knotted two broken ends in the sacking of his load.

‘Whore of Babylon,’ said the man, forcing the knots tight; and he muttered continually as he turned the bundle over and over to verify the fastenings. ‘What is your name?’ he asked.

‘Martin Kaftan.’

‘Where do you come from?’

‘France.’

‘Where are you going? Are you alone? Do you know anyone in Encantats?’

Martin answered these questions, and after a pause the man, pretending to inspect his burden still, drew out a knife. He feigned to cut the loose end of a string and said, ‘You know nothing about the mountain. Look at your shoes. I dare say you have a good many pairs of leather shoes in your house,’ he added, with a cunning leer. Martin looked at his shoes: their soles were shining from the grass; they were indeed quite unsuitable. ‘Come,’ said the man, ‘let me scratch them with my knife.’

With the shoes in front of him he did not scratch them yet, but pushed up his sleeve and began to shave the hair on his forearm. The hairs skipped under the edge, leaving a bare, mown tract of skin. ‘Sharp,’ he said. ‘That’s what I call sharp.’ He was looking uglier now, with white spittle between his lips, his eyes were squinting with excitement, and the defect in his speech grew more pronounced. He said, ‘You are afraid to be on the mountain alone with all that money and your fine coat. Let me feel your coat. What have you got to eat?’

Martin laughed, leaning back against the rock. He said, ‘How would I be afraid on the mountain, my dear? And no one can rob me on this journey, because I was robbed before I began. The coat is not mine, and I left all my food at the top of the forest, by mistake: a chicken, bread, and a bottle of wine. What is your name, pray?’

‘Joan,’ said the man, vaguely. He seemed to be coming out of his fit, and although he said ‘No,’ when Martin asked him whether he had anything to eat either, after a little while he brought out a flat black loaf and two onions and unslung the greasy leather bottle he wore on his shoulder. He scratched a cross on the loaf, cut off a piece and gave it to Martin with one of the onions; and when Martin held out his hand for the knife to slice th

e onion he passed it without reflection. He also passed the wine.

Munching fast he told Martin how good he was: uniquely good: took no advantage of the situation as any other man might, nay would, for the laws of God were not observed and God Himself had never reached these parts. ‘There was the izard-hunter from Politg – they cut his throat in this very pass before he could say hail Mary and Espollabalitris ate his balls.’

‘What are izards?’

‘Izards are what you make chamois-skin out of: where were you brought up, God forbid? But I should never have eaten any Christian’s balls. I am too good,’ he said with his eyes closed tight, and he pressed Martin to eat more, to drink as much as he could. ‘Drink, man, drink. I do not reckon the cost,’ he said, squirting the jet into Martin’s mouth.

‘You are very kind,’ said Martin, when the skin was empty. ‘I hope you will find my chicken, in time, and the bottle. They are in a paper carrier-bag, on a rock where the trees begin.’

‘Never mind, never mind if the bears have had them. I can go all day and night without refreshment, to help a poor man. I do good, but I never mention it. There are hundreds and thousands down there’ – jerking his head backwards – ‘who owe everything to me: but I say nothing.’ Shading his mouth he whispered, ‘There are evil tongues down there,’ and nodding vehemently he set to scratching the shoes, raising diagonal weals on their soles with the point of his knife.

‘Thank you very much,’ said Martin, making to put them on.

‘No, no. Let me,’ cried Joan, cramming them on to Martin’s feet and lacing them with terrible force. He grew excited again when he described the course of the path as it led on to the Cami Real, the great mule-track, confused in his description, obscurely angry and contentious; his ugliness was increasing fast, but when Martin said he supposed the burden must weigh a great deal Joan turned off directly to tell what he could carry, compared with common men. And indeed when Martin lifted it, meaning to help it on, the weight was staggering. Joan thrust him aside, swung it up with one hand, looped it on with a sordid web and stood displaying himself with angry satisfaction. ‘Watch me,’ he cried, setting off at a furious pace up the hill. His voice came fainter: ‘You have never seen anything like it. But this is nothing to what I can do, Mother of God.’

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

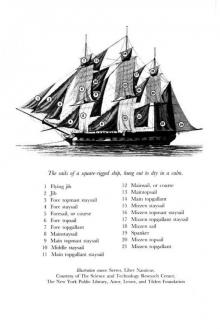

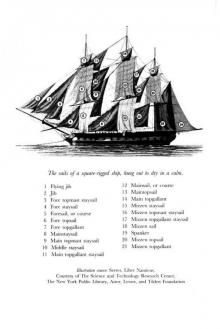

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea