- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Wine-Dark Sea Page 14

The Wine-Dark Sea Read online

Page 14

Stephen thought about her most affectionately: it was her courage that he most admired—she had had a very hard life in London and an appalling one in the convict settlement of New South Wales, but she had borne up admirably, retaining her own particular integrity: no self-pity, no complaint. And although he was aware that this courage might be accompanied by a certain ferocity (she had been transported for blowing a man's head off) he did not find it affected his esteem.

As for her person, he liked that too: little evident immediate prettiness, but a slim, agreeable figure and a very fine carriage. She was not as beautiful as Diana with her black hair and blue eyes, but they both had the same straight back, the same thoroughbred grace of movement and the same small head held high; though in Clarissa's case it was fair. Something of the same kind of courage, too: he hoped they would be friends. It was true that Diana's house contained Brigid, the daughter whom Stephen had not yet seen, and upon the whole Clarissa disliked children; yet Clarissa was a well-bred woman, affectionate in her own way, and unless the baby or rather little girl by now were quite exceptionally disagreeable, which he could not believe, she would probably make an exception.

Bells, bells, bells, and long wandering thoughts between them: Martin quiescent.

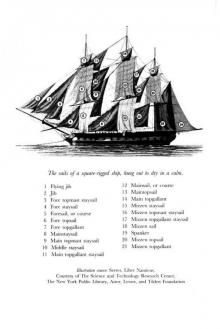

Eight bells, and the starbowlines, after a trying watch with frequent trimming of sail, taking reefs in and shaking them out, with much toil and anxiety over the rain-water, separating the foul from the clean, and with very frequent soakings, hurried below through the downpour to drip more or less dry in their hammocks.

Jack remained on deck. The wind had slackened a little and it was now coming in over the frigate's quarter; the sea was less lumpy: if this continued, and it was likely to do so, he could soon set topgallants. But neither the set of the sea nor the wind was his first concern at present. During the night they had lost the Franklin, and unless they could find her again their sweep would be nothing like so efficient; besides, with even the remote prospect of an action his aim was always to bring a wholly decisive force into play. He was scarcely what would be called a timid man, but he far preferred a bloodless battle; often and often he had risked his people and his ship, yet never when there was a real possibility of having such a weight of metal within range that no enemy in his right mind would resist—colours struck, no blood shed, no harm done, valuable powder returned to the magazine, and honour saved all round. He was, after all, a professional man of war, not a hero. This fellow, however, was said to be a pirate. Shelton had seen the black flag. And if he was a pirate there was likely to be resistance or flight. Yet might it not have been that the Jolly Roger was hoisted for a cod, or as a way of disarming his legitimate privateer's prey by terror? Jack had known it done. True piracy was almost unheard of in these waters, whatever might be the case elsewhere; though some privateers, far and far from land, might sometimes overstep the mark. And surely no downright pirate would have let a well-charged whaler go? The Surprise cared for neither flight nor fight: but still he did not want her scratched, nor any of her precious sailcloth and cordage hurt, and few sights would be more welcome than the Franklin.

Her top-lantern had vanished during the first three squalls of the night, reappearing in her due station on the starboard beam as each cleared, as much as it did clear in this thick weather. Yet after the long-lasting fourth it was no longer to be seen. At that time the wind was right aft, and this was the one point of sailing in which the Franklin, a remarkably well-built little craft, could draw away from the Surprise: Tom Pullings, the soul of rectitude, would never mean to do so, but with such a following sea the log-line was a most fallible guide and Jack therefore gazed steadily through the murk forward, over the starboard bow.

Even the murk was lessening, too: and although the southeast was impenetrably black with the last squall racing from them there were distinct rifts in the cloud astern, with stars showing clear. He had a momentary glimpse of Rigel Kent just above the crossjack-yard; and with Rigel Kent at that height dawn was no great way off.

He also caught sight of Killick by the binnacle, holding an unnecessary napkin. 'Mr Wilkins,' he said to the officer of the watch, 'I am going below. I am to be called if there is any change in the wind, or if any sail is sighted.'

He ran down the companion-ladder and into the welcome scent of coffee, the pot sitting there in gimbals, under a lantern. He gathered his hair—like most of the ship's company he wore it long, but whereas the seamen's pigtails hung straight down behind, Jack's was clubbed, doubled back and held with a bow: yet all but the few close-cropped men had undone their plaits to let their salt-laden hair profit from the downpour; and very disagreeable they looked, upon the whole, with long dank strands plastered about their upper persons, bare in this warm rain—he gathered his hair, wrung it out, tied it loosely with a handkerchief, drank three cups of coffee with intense appreciation, ate an ancient biscuit, and called for towels. Putting them under his wet head he stretched out on the stern locker, asked for news of the doctor, heard Killick's 'Quiet as the grave, sir,' nodded, and went straight to sleep in spite of the strong coffee and the even stronger thunder of the wave-crests torn off by the wind and striking the deadlights that protected the flight of stern-windows six inches from his left ear.

'Sir, sir,' called a voice in his right ear, a tremulous voice, the tall, shy, burly Norton sent to wake his commander.

'What is it, Mr Norton?'

'Mr Wilkins thinks he may hear gunfire, sir.'

'Thank you. Tell him I shall be on deck directly.'

Jack leapt up. He was draining the cold coffee-pot when Norton put his head back through the door and said, 'Which he sent his compliments and duty, too, sir.'

By the time the Surprise had pitched once, with a slight corkscrew roll, Jack was at the head of the ladder in the dim half-light. 'Good morning, Mr Wilkins,' he said. 'Where away?'

'On the starboard bow, sir. It might be thunder, but I thought . . .'

It might well have been thunder, from the lightning-shot blackness over there. 'Masthead. Oh masthead. What do you see?'

'Nothing, sir,' called the lookout. 'Black as Hell down there.'

Away to the larboard the sun had risen twenty minutes ago. The scud overhead was grey, and through gaps in it lighter clouds and even whitish sky could be seen. Ahead and on the starboard bow all was black indeed: astern, quite far astern, all was blacker still. The wind had hauled forward half a point, blowing with almost the same force; the sea was more regular by far—heavy still, but no cross-current.

All those on deck were motionless: some with swabs poised, some with buckets and holystones, unconscious of their immediate surroundings, every man's face turned earnestly, with the utmost concentration, to the blue-black east-south-east.

A criss-cross of lightning down over there: then a low rumble, accompanied by a sharp crack or two. Every man looked at his mate, as Wilkins looked at his Captain. 'Perhaps,' said Jack. 'The arms chests into the half-deck, at all events.'

Minutes, indecisive minutes passed: the cleaning of the deck resumed: a work of superogation, if ever there was one. Wilkins sent two more hands to the wheel, for the squall astern was coming up fast in their wake. 'This may well be the last,' said Jack, seeing a patch of blue right overhead. He walked aft, leant over the heaving taffrail and watched the squall approach, as dark as well could be and lit from within by innumerable flashes, like all those that had passed over them that night. The blue was utterly banished, the day darkened. 'Come up the sheets,' he called.

For the last quarter of a mile the squall was a distinct entity, sombre purple, sky-tall, curving over at the top and with white water all along its foot, now covering half the horizon and sweeping along at an inconceivable speed for such a bulk.

Then it was upon them. Blinding rain, shattered water driving so thick among the great heavy drops that one could hardly breathe; and the ship, as though given some frightful spur, leapt forward in the dark confused turmoil of water.

While th

e forefront of the squall enveloped them and for quite long after its extreme violence had passed on ahead, time had little meaning; but as the enormous rain dwindled to little more than a shower and the wind returned to its strong steady southeast course, the men at the wheel eased their powerful grip, breathing freely and nodding to one another and the sodden quartermaster, the sheets were hauled aft, the ship, jetting rainwater from her scuppers, sailed on, accompanied for some time by low cloud that thinned and thinned and then quite suddenly revealed high blue sunlit sky: a few minutes later the sun himself heaved out of the lead-coloured bank to larboard. This had indeed been the last of the series: the Surprise sailed on after it, directly in its track as it raced to the south-east, covering a vast breadth of sea with its darkness.

On and on, and now with the sun they could clearly distinguish the squall's grim front from its grey, thinner tail, followed by a stretch of brilliant clarity: and at a given moment the foremast lookout's screaming hail 'Sail ho! Two sail of ships on the starboard bow. On deck, there, two sails of ships on the starboard bow' brought no news, for they were already hull up as the darkness passed over and beyond them, suddenly present and clear to every man aboard.

Jack was on his way to the foretop before the repetition. He levelled his glass for the first details, though the first glance had shown the essence of the matter. The nearer ship was the four-masted Alastor, wearing the black flag; she was grappled tight to the Franklin; they were fighting hand to hand on deck and between decks and now of course there was no gunfire. Small arms, but no cannon.

'All hands, all hands,' he called. 'Topgallants.' He gauged their effect; certainly she could bear them and more. From the quarterdeck now he called for studdingsails alow and aloft, and then for royals.

'Heave the log, Mr Reade,' he said. He had brought the Alastor right ahead, broadside on, and in his glass he could see her trying to cast off, the Franklin resisting the attempt.

'Ten and one fathom, sir, if you please,' said Reade at his side.

Jack nodded. The grappled ships were some two miles off. If nothing carried away he should be alongside in ten minutes, for the Surprise would gather speed. Tom would hold on for ten minutes if he had to do it with his teeth.

'Mr Grainger,' he said, 'beat to quarters.'

It was the thunder of the drum, the piping and the cries down the hatchways, the deep growl and thump of guns being run out and the hurrying of feet that roused Martin. 'Is that you, Maturin?' he whispered, with a terrified sideways glance.

'It is,' said Stephen, taking his wrist. 'Good day to you, now.'

'Oh thank God, thank God, thank God,' said Martin, his voice broken with the horror of it. 'I thought I was dead and in Hell. This terrible room. Oh this terrible, terrible room.'

The pulse was now extremely agitated. The patient was growing more so. 'Maturin, my wits are astray—I am barely out of a night-long nightmare—forgive me my trespasses to you.'

'If you please, sir,' said Reade, coming in, 'the Captain enquires for Mr Martin and desires me to tell the Doctor that we are bearing down on a heavy pirate engaged with the Franklin: there will be some broken omelets presently.'

'Thank you, Mr Reade: Mr Martin is far from well.' And calling after him, 'I shall repair to my station very soon.'

'May I come?' cried Martin.

'You may not,' said Stephen. 'You can barely stand, my poor colleague, sick as you are.'

'Pray take me. I cannot bear to be left in this room: I hate and dread it. I could not bring myself to pass by its door, even. This is where I . . . this is where Mrs Oakes . . . the wages of sin is death . . . I am rotting here in this life, while in the next . . . Christe eleison.'

'Kyrie eleison,' said Stephen. 'But listen, Nathaniel, will you? You are not rotting as the seamen put it: not at all. These are salt-sores: they are no more, unless you have taken some improper physic. In this ship you could not have contracted any infection of that kind. There has been no source of infection, whether by kissing, toying, drinking in the same cup, or otherwise: none whatsoever. I state that as a physician.'

The wind had hauled a little farther forward, and with her astonishing spread of drum-tight canvas the Surprise was now running at such a pace that the following seas lapped idly alongside. From high aloft Jack made out the confused situation with fair certainty: the ships were still grappled fast: the Alastors had boarded the Franklin's waist but Tom had run up stout close-quarters and some of his people were holding out behind them while others had invaded the Alastor's forecastle and were fighting the Frenchmen there. Some of the Alastors were still trying to cast off, and still the Franklins prevented them—Jack could see the bearded Sethians in the furious struggle that flung three Frenchmen bodily off the lashed bowsprits. Another group of pirates were turning one of the Franklin's forward carronades aft to blast a way through the close-quarters; but the mob of their own men and deadly musket-fire from their own forecastle hindered them, and the carronade ran wild on the rolling deck, out of control.

Jack called down: 'Chasers' crew away. Run them out.' He landed on the deck with a thump, ran through the eager, attentive, well-armed groups to the bows, where his own brass Beelzebub was reaching far out of the port. 'Foretopsail,' he said, and they heaved the gun round. He and Bonden pointed it with grunts and half-words, the whole crew working as one man. Glaring along the sights Jack pulled the laniard, arched for the gun's recoil beneath him and through the bellowing crash he roared, 'T'other.'

The smoke raced away before them, and barely was it clear before the other chaser fired. Both shots fulfilled their only function, piercing the foretopsail they were aimed at, dismaying the Alastors—few ships could fire so clean—and encouraging the Franklins, whose cheer could now be heard, though faint and thin.

But these two shots, reverberating through the ship's hollow belly, sent poor Martin's weakened mind clear off its precarious balance and into a delirium. His distress became very great, reaching the screaming pitch. Stephen quickly fastened him into his cot with two bandages and ran towards the sick-berth. He met Padeen on his way to tell him that quarters had been beaten. 'I know it,' he replied. 'Go straight along and sit with Mr Martin. I shall come back.'

He returned with the fittest of his patients, a recent hernia. 'See that all is well below, Padeen,' he said, and when Padeen had gone he measured out a powerful dose from his secret store of laudanum, the tincture of opium to which he and Padeen had once been so addicted. 'Now, John,' he said to the seaman, 'hold up his shoulders.' And in pause, 'Nathaniel, Nathaniel my dear, here is your draught. Down it in one swallow, I beg.'

The pause drew out. 'Lay him back, lay him back gently,' said Stephen. 'He will be quiet now, with the blessing. But you will sit with him, John, and soothe his mind if he wakes.'

'Shipmates,' cried Jack from the break of the quarterdeck, 'I am going to lay alongside the four-master as easy as can be. Some of our people are on her forecastle; some of theirs are trying to work aft in the Franklin. So as soon as we are fast, come along with me and we will clear the four-master's waist, then carry on to relieve Captain Pullings. But Mr Grainger's division will go straight along the Alastor's gun-deck to stop them turning awkward with their cannon. None of you can go wrong if you knock an enemy on the head.'

The seamen—a savage looking crew with their long hair still wild about them—the seamen cheered, a strangely happy sound as the frigate glided in towards those embattled ships: roaring shouts, the clash of bitter fighting clear and clearer over the narrowing sea.

He stepped to the wheel, his heavy sword dangling from his wrist by a strap and he took her shaving in, his heart beating high and his face gleaming, until her yards caught in the Alastor's shrouds and the ships ground together.

'Follow me, follow me,' he cried, leaping across, and on either side of him there were Surprises, swarming over with cutlasses, pistols, boarding-axes. Bonden was at his right hand, Awkward Davies on his left, already foaming at the mouth. The Alastor

s came at them with furious spirit and in the very first clash, halfway across the deck, one shot Jack's hat from his head, the bullet scoring his skull, and another, lunging with a long pike, brought him down.

'The Captain's down,' shrieked Davies. He cut the pikeman's legs from under him and Bonden split his head. Davies went on hacking the body as the Franklins came howling down and took the Alastors in the flank.

There was an extremely dense and savage melee with barely room to strike—cruel blows for all that and pistols touching the enemy's face. The battle surged forward and back, more joined in, forward and back, turning, trampling on bodies dead and living, all sense of direction lost, a slaughter momentarily interrupted by the crash of the Franklin's carronade, turned and fired at last, but misfired, misaimed so that it killed many of those it was meant to help. The remaining Alastors came flooding back into their own ship, instantly pursued by Pullings' men, who cut them down from behind while the Surprises shattered them from in front and either side, for they had all heard the cry 'The Captain's down—they've got the Captain' and the fighting reached an extraordinary degree of ferocity.

Presently it was no more than broken men, escaping below, screaming as they were hunted down and killed: and an awful silence fell, only the ships creaking together on the dying sea, and the flapping of empty sails.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

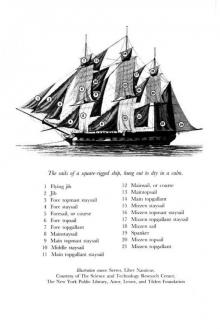

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

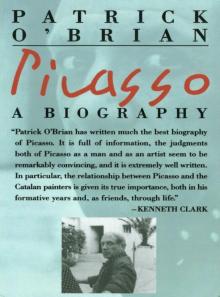

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea