- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

H.M.S. Surprise Page 13

H.M.S. Surprise Read online

Page 13

'How very good-natured of you,' cried Stephen, looking into Nicolls' face—somewhat vinous, but perfectly in command of himself. 'I should be infinitely obliged. Give me leave to fetch a hammer, some small boxes, a hat, and I am with you.'

They crawled along the barge, the launch and one of the cutters to the jolly-boat—they were all towing behind, to prevent them opening in the heat—and rowed away. The cheerful noise faded behind them; their wake lengthened across the glassy sea. Stephen took off his clothes and sat naked in his sennit hat; he revelled in the heat, and this had been his daily practice since the latitude of Madeira. At present he was a disagreeable mottled dun colour from head to foot, the initial brown having darkened to a suffused grey; he was not much given to washing—fresh water was not to be had, in any event—and the salt from his swimming lay upon him like dust.

'I was contemplating upon sea-officers just now,' he observed, 'and trying to name the qualities that make one cry, "That man is a sailor, in the meliorative sense". From that I went on to reflect that the typical sea-officer is as rare as your anatomically typical corpse; that is to say, he is surrounded by what for want of a better word I may call unsatisfactory specimens, or sub-species. And I was carried on to the reflection that whereas there are many good or at least amiable midshipmen, there are fewer good lieutenants, still fewer good captains, and almost no good admirals. A possible explanation may be this: in addition to professional competence, cheerful resignation, an excellent liver, natural authority and a hundred other virtues, there must be the far rarer quality of resisting the effects, the dehumanising effects, of the exercise of authority. Authority is a solvent of humanity: look at any husband, any father of a family, and note the absorption of the person by the persona, the individual by the role. Then multiply the family, and the authority, by some hundreds and see the effect upon a sea-captain, to say nothing of an absolute monarch. Surely man in general is born to be oppressed or solitary, if he is to be fully human; unless it so happens that he is immune to the poison. In the nature of the service this immunity cannot be detected until late: but it certainly exists. How otherwise are we to account for the rare, but fully human and therefore efficient admirals we see, such as Duncan, Nelson . . .'

He saw that Nicolls's attention had wandered and he let his voice die away to a murmur with no apparent end, took a book from his coat pocket and, since the nearer sky was empty of birds, fell to reading in it. The oars squeaked against the tholes, the blades dipped with a steady beat, and the sun beat down: the boat crept across the sea.

From time to time Stephen looked up, repeating his Urdu phrases and considering Nicolls's face. The man was in a bad way, and had been for some time. Bad at Gibraltar, bad at Madeira, worse since St Jago. Scurvy was out of the question in this case: syphilis, worms?

'I beg your pardon,' said Nicolls with an artificial smile. 'I am afraid I lost the thread. What were you saying?'

'I was repeating phrases from this little book. It is all I could get, apart from the Fort William grammar, which is in my cabin. It is a phrase-book, and I believe it must have been compiled by a disappointed man: My horse has been eaten by a tiger, leopard, bear; I wish to hire a palanquin; there are no palanquins in this town, sir—all my money has been stolen; I wish to speak to the Collector: the Collector is dead, sir—I have been beaten by evil men. Yet salacious too, poor burning soul: Woman, wilt thou lie with me?'

With an effort at civil interest Nicolls said, 'Is that the language you speak with Achmet?'

'Yes, indeed. All our Lascars speak it, although they come from widely different parts of India: it is their lingua franca. I chose Achmet because it is his mother-tongue; and he is an obliging, patient fellow. But he cannot read or write, and that is why I ply my grammar, in the hope of fixing the colloquial: do you not find that a spoken language wafts in and out of your mind, leaving little trace unless you anchor it with print?'

'I can't say I do: I am no hand at talking foreign—never was. It quite astonishes me to hear you rattling away with those black men. Even in English, when it comes to anything more delicate than making sail, I find it . . .' He paused, looked over his shoulder and said there was no landing this side; it was too steep-to; but they might do better on the other. The number of birds had been increasing as they neared the rock, and now as they pulled round to its southern side the terns and boobies were thick overhead, flying in and out from their fishing-grounds in a bewildering intricacy of crossing paths, the birds all strangely mute. Stephen gazed up into them, equally silent, lost in admiration, until the boat grounded on weed-muffled rock and tilted as Nicolls ran it up into a sheltered inlet, heaved it clear of the swell, and handed Stephen out.

'Thank you, thank you,' said Stephen, scrambling up the dark sea-washed band to the shining white surface beyond: and there he stopped dead. Immediately in front of his nose, almost touching it, there was a sitting booby. Two, four, six boobies, as white as the bare rock they sat on—a carpet of boobies, young and old; and among them quantities of terns. The nearest booby looked at him without much interest; a slight degree of irritation was all he could detect in that long reptilian face and bright round eye. He advanced his finger and touched the bird, which shrugged its person; and as he did so a great rush of wings filled the air—another booby landing with a full crop for its huge gaping child on the naked rock a few feet away. 'Jesus, Mary and Joseph,' he murmured, straightening to survey the island, a smooth mound like a vast worn molar tooth, with birds thick in all the hollows. The hot air was full of their sound, coming and going; full of the ammoniac smell of their droppings and the reek of fish; and all over the hard white surface it shimmered in the heat and the intolerable glare so that birds fifty yards up the slope could hardly be focused and the ridge of the mound wavered like a taut rope that had been plucked. Waterless, totally arid. Not a blade of grass, not a weed, not a lichen: stench, blazing rock and unmoving air. 'This is a paradise,' cried Stephen.

'I am glad you like it,' said Nicolls, sitting wearily down on the only clean spot he could find. 'You don't find it rather strong for paradise, and hell-fire hot? The rock is burning through my shoes.'

'There is an odour, sure,' said Stephen. 'But by paradise I mean the tameness of the fowl; and I do not believe it is they that smell.' He ducked as a tern shot past his head, banking and braking hard to land. 'The tameness of the birds before the Fall. I believe this bird will suffer me to smell it; I believe that much, if not all the odour is that of excrement, dead fish, and weed.' He moved a little closer to the booby, one of the few still sitting on an egg, knelt by it, gently took its wicked beak and put his nose to its back. 'They contribute a good deal, however,' he said. The booby looked indignant, ruffled, impenetrably stupid; it uttered a low hiss, but it did not move away—merely shuffled the egg beneath it and stared at a crab that was laboriously stealing a flying-fish, left by a tern at the edge of a nest two feet away.

From the top of the island he could see the frigate, lying motionless two miles off, her sails slack and dispirited: he had left Nicolls under a shelter made from their clothes spread on the oars, the only patch of shade on this whole marvellous rock. He had collected two boobies and two terns: he had had to overcome an extreme reluctance to knock them on the head, but one of the boobies, the red-legged booby, was almost certainly of an undescribed species; he had chosen birds that were not breeding, and by his estimate of this rock alone there were some thirty-five thousand left. He had filled his boxes with several specimens of a feather-eating moth, a beetle of an unknown genus, two woodlice apparently identical with those from an Irish turf stack, the agile thievish crab, and a large number of ticks and wingless flies that he would classify in time. Such a haul! Now he was beating the rock with his hammer, not for geological specimens, for they were already piled in the boat, but to widen a crevice in which an unidentified arachnid had taken refuge. The rock was hard; the crevice deep; the arachnid stubborn. From time to time he paused to breathe the somewhat

purer air up here and to look out towards the ship: eastwards there were far fewer birds, though here and there a gannet cruised or dived with closed wings, plummeting into the sea. When he dissected these specimens he should pay particular attention to their nostrils; there might well be a process that prevented the inrush of water.

Nicolls. The flow, the burst of confidence, hingeing upon what chance word? Something tolerably remote, since he could not remember it, had led to the abrupt statement, 'I was ashore from the time Euryalus paid off until I was appointed to the Surprise; and I had a disagreement with my wife.' Protestants often confessed to medical men and Stephen had heard this history before, always with the ritual plea for advice—the bitterly wounded wife, the wretched husband trying to atone, the civil imitation of a married life, the guarded words, politeness, restraint, resentment, the blank misery of nights and waking, the progressive decay of all friendship and communication—but he had never heard it expressed with such piercing desolate unhappiness, 'I had thought it might be better when I was afloat,' said Nicolls, 'but it was not. Then no letter at Gibraltar, although Leopard was there before us, and Swiftsure: every time I had the middle watch I used to walk up and down composing the answer I should send to the letters that would be waiting for me at Madeira. There were no letters. The packet had come and gone a fortnight before, while we were still in Gibraltar; and there were no letters. I had really thought there must be a remaining . . . but, however, not so much as a note. I could not believe it, all the way down the trades; but now I do, and I tell you, Maturin, I cannot bear it, not this long, slow death.'

'There is certain to be a whole bundle of them at Rio,' said Stephen. 'I, too, received none at Madeira—virtually none. They are sure to be sent to Rio, rely upon it; or even to Bombay.'

'No,' said Nicolls, with a toneless certainty. 'There will be no letters any more. I have bored you too long with my affairs: forgive me. If I were to rig a shelter with the oars and my shirt, would you like to sit down under it? Surely this heat will give you a sunstroke?'

'No, I thank you. Time is all too short. I must quickly explore this stationary ark—the Dear knows when I shall see it again.'

Stephen hoped Nicolls would not resent it later. Regular confession was far more formal, far less detailed and spreading, far less satisfactory in its unsacramental aspect; but at least a confessor was a priest his whole life through, whereas a doctor was an ordinary being much of the time—difficult to face over the dinner-table after such privities.

He returned to his task, thump, thump, thump. Pause: thump, thump, thump. And as the crevice slowly widened he noticed great drops falling on the rock, drying as they fell. 'I should not have thought I had any sweat left,' he reflected, thumping on. Then he realised that drops were also falling on his back, huge drops of warm rain, quite unlike the dung the countless birds had gratified him with.

He stood up, looked round, and there barring the western sky was a darkness, and on the sea beneath it a white line, approaching with inconceivable rapidity. No birds in the air, even on the crowded western side. And the middle distance was blurred by flying rain. The whole of the darkness was lit from within by red lightning, plain even in this glare. A moment later the sun was swallowed up and in the hot gloom water hurtled down upon him. Not drops, but jets, as warm as the air and driving flatways with enormous force; and between the close-packed jets a spray of shattered water, infinitely divided, so thick he could hardly draw in the air. He sheltered his mouth with his hands, breathed easier, let water gush through his fingers and drank it up, pint after pint. Although he was on the dome of the rock the deluge covered his ankles, and there were his boxes blowing, floating away. Staggering and crouching in the wind he recovered two and squatted over them; and all the time the rain raced through the air, filling his ears with a roar that almost drowned the prodigious thunder. Now the squall was right overhead; the turning wind knocked him down, and what he had thought the ultimate degree of cataclysm increased tenfold. He wedged the boxes between his knees and crouched on all fours.

Time took on another aspect; it was marked only by the successive lightning-strokes that hissed through the air, darting from the cloud above, striking the rock and leaping back into the darkness. A few weak, stunned thoughts moved through his mind—'What of the ship? Can any bird survive this? Is Nicolls safe?'

It was over. The rain stopped instantly and the wind swept the air clear; a few minutes later the cloud had passed from the lowering sun and it rode there, blazing from a perfect, even bluer sky. To westward the world was unchanged, just as it always had been apart from white caps on the sea; to the east the squall still covered the place he had last seen the ship; and in the widening sunlit stretch between the rock and the darkness a current bore a stream of fledgling birds, hundreds of them. And all along the stream he saw sharks, some large, some small, rising to the bodies.

The whole rock was still streaming—the sound of running water everywhere. He splashed down the slope calling 'Nicolls, Nicolls!' Some of the birds—he had to avoid them as he stepped—were still crouching flat over their eggs or nestlings; some were preening themselves. In three places there were jagged rows of dead terns and gannets, charred though damp, and smelling of the fire. He reached the spot where the shelter had been: no shelter, no fallen oars: and where they had hauled up the boat there was no boat.

He made his way clean round the rock, leaning on the wind and calling in the emptiness. And when for the second time he came to the eastern side and looked out to sea the squall had vanished. There was no ship to be seen. Climbing to the top he caught sight of her, hull down and scudding before the wind under her foretopsail, her mizzen and main-topmast gone. He watched until even the flicker of white disappeared. The sun had dipped below the horizon when he turned and walked down. The boobies had already set to their fishing again, and the higher birds were still in the sun, flashing pink as they dived through the fiery light.

Chapter Six

It was the barge that took him off at last, the barge under Babbington, with a powerful crew pulling double-banked right into the eye of the wind.

'Are you all right, sir?' he shouted, as soon as they saw him sitting there. Stephen made no reply, but pointed for the boat to come round the other side..

'Are you all right, sir?' cried Babbington again, leaping ashore. 'Where is Mr Nicolls?'

Stephen nodded, and in a low croak he said, 'I am perfectly well, I thank you. But poor Mr Nicolls . . . Do you have any water in that boat?'

'Light along the keg, there. Bear a hand, bear a hand.'

Water. It flowed into him, irrigating his blackened mouth and cracking throat, filling his wizened body until his skin broke out into a sweat at last; and they stood over him, wondering, solicitous, respectful, shadowing him with a piece of sailcloth. They had not expected to find him alive: the disappearance of Nicolls was in the natural course of events. 'Is there enough for all?' he asked in a more human tone, pausing.

'Plenty, sir, plenty; another couple of breakers,' said Bonden. 'But sir, do you think it right? You won't burst on us?'

He drank, closing his eyes to savour the delight. 'A sharper pleasure than love, more immediate, intense.' In time he opened them again and called out in a strong voice, 'Stop that at once. You, sir, put that booby down. Stop it, I say, you murderous damned raparees, for shame. And leave those stones alone.'

'O'Connor, Boguslavsky, Brown, the rest of you, get back into the boat,' cried Babbington. 'Now, sir, could you take a little something? Soup? A ham sandwich? A piece of cake?'

'I believe not, thank you. If you will be so good as to have those birds, stones, eggs, handed into the boat, and to carry the two small boxes yourself, perhaps we may shove off. How is the ship? Where is it?'

'Four or five leagues south by cast, sir: perhaps you saw our topgallants yesterday evening?'

'Not I. Is she damaged—people hurt?'

'Pretty well battered, sir. All aboard, Bonden? Easy, sir, easy

now: Plumb, bundle up that shirt for a pillow. Bonden, what are you at?'

'I'm coming it the umbrella, sir. I thought as maybe you wouldn't mind taking the tiller.'

'Shove off,' cried Babbington. 'Give way.' The barge shot from the rock, swung round, hoisted jib and mainsail and sped away to the south-cast. 'Well, sir,' he said, settling to the tiller with the compass before him, 'I'm afraid she was rather knocked about, and we lost some people: old Tiddiman was swept out of the heads and three of the boys went adrift before we could get them inboard. We were so busy looking at the sky in the west that we never had a hint of the white squall.'

'White? Sure it was as black as an open grave.'

'That was the second. The first was a white squall from due south, a few minutes before yours: it often happens near the line, they say, but not so God-damn hard. Anyhow, it hit us without a word of warning—the Captain was below at the time, in the sail-room—hit us tops'l high—almost nothing on the surface and laid us on our beam-ends. Every sail blown clean out of its bolt-rope before we could touch the sheets or halliards; not a scrap of canvas left.'

'Even the pendant went,' said Bonden.

'Yes, even the pendant went: amazing. And main and mizzen topmasts and foretopgallant, all over to leeward, and there we were on our beam-ends, all ports open and three guns breaking loose. Then there was the Captain on deck with an axe in his hand, singing out and clearing all away, and she righted. But we had hardly got her head round before the black squall hit us—Lord!'

'We got a scrap of canvas on to the foretopmast,' said Bonden, 'and scudded, there being these guns adrift on deck and the Captain wishful they should not burst through the side.'

'I was at the weather-earing,' said Plumb, stern-oar, 'and it took me half a glass to pass it; and it blew so hard it whipped my pig-tail close to the boom-iron, took a double turn in it, and Dick Turnbull had to cut me loose. That was a cruel hard moment, sir.' He turned his head to show the loss—fifteen years of careful plaiting, combing, encouraging with best Macassar oil, reduced to a bristly stump three inches long.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

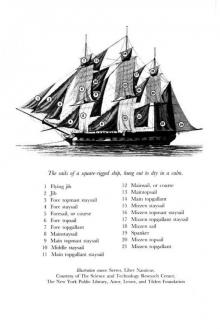

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea