- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Mauritius Command Page 11

The Mauritius Command Read online

Page 11

The ritual offerings appeared, brought in by a black boy in a turban, and Jack and Clonfert were left alone: a certain awkwardness became manifest at once. With advancing years Jack had learnt the value of silence in a situation where he did not know what to say. Clonfert, though slightly older in spite of his youthful appearance, had not, and he talked—these baubles were from his Syrian campaign with Sir Sydney—the lamp a present from Dgezzar Pasha—the scimitar on the right from the Maronite Patriarch—he had grown so used to Eastern ways that he could not do without his sofa. Would not the Commodore sit down? The Commodore had no notion of lowering himself to within inches of the deck—what could he do with his legs?—and replied that he should as soon keep an eye on the Boadicea's boats as they pulled briskly between the arsenal and the frigate, filling her magazines and shot-lockers with what he hoped would prove a most persuasive argument. Then the Commodore would surely taste a little of this Constantia and toy with an Aleppo fig: Clonfert conceived that they made an interesting combination. Or perhaps a trifle of this botargo?

'I am infinitely obliged to you, Clonfert,' said Jack, 'and I am sure your wine is prodigious good; but the fact of the matter is, that Sirius gave me a great deal of capital port and Néréide a great deal of capital Madeira; so what I should really prize beyond anything at this moment is a cup of coffee, if that is possible' ' '

It was not possible. Clonfert was mortified, chagrined, desolated, but he drank no coffee; nor did his officers. He really was mortified, chagrined and desolated, too. He had already been obliged to apologize for not having his statement of condition ready, and this fresh blow, this social blow, cast him down extremely. Jack wanted no more unpleasantness in the squadron than already existed; and even on the grounds of common humanity he did not wish to leave Clonfert under what he evidently considered a great moral disadvantage; so pacing over to a fine narwhal tusk leaning in a corner he said, in an obliging manner, 'This is an uncommonly fine tusk.'

'A handsome object, is it not? But with submission, sir, I believe horn is the proper term. It comes from a unicorn. Sir Sydney gave it to me. He shot the beast himself, having singled it out from a troop of antelopes; it led him a tremendous chase, though he was mounted on Hassan Bey's own stallion—five and twenty miles through the trackless desert. The Turks and Arabs were perfectly amazed. He told me they said they had never seen anything like his horsemanship, nor the way he shot the unicorn at full gallop. They were astounded.'

'I am sure they were,, said Jack. He turned it in his hands, and said, with a smile, 'So I can boast of having held a true unicorn's horn.'

'You may take your oath on it, sir. I cut it out of the creature's head myself.'

'How the poor fellow does expose himself,' thought Jack, on his way back to the Raisonable: he had had a narwhal tusk in his cabin for months, bringing it back from the north for Stephen Maturin, and he was perfectly acquainted with the solid heft of its ivory, so very far removed from horn. Yet Clonfert had probably thought that the first part was true. Admiral Smith was a remarkably vain and boastful man, quite capable of that foolish tale: yet at the same time Admiral Smith was a most capable and enterprising officer. Apart from other brilliant actions, he had defeated Buonaparte at Acre: not many men had such grounds for boasting. Perhaps Clonfert was of that same strange build? Jack hoped so with all his heart—Clonfert might show away with all the unicorns in the world as far as Jack was concerned, and lions too, so long as he also produced something like the same results.

His meagre belongings had already come across from the Boadicea; they had already been arranged by his own steward as he liked them to be arranged, and with a contented sigh Jack sat easy in an old Windsor chair with arms, flinging his heavy full-dress coat on to a locker. Killick did not like seeing clothes thrown about: Killick would have to lump it.

But Killick, who had dashed boiling water on to freshly-ground coffee the moment the Raisonable's barge shoved off from the Otter, was a new man. Once cross-grained, shrewish, complaining, a master of dumb and sometimes vocal insolence, he was now almost complaisant. He brought in the coffee, watched Jack drink it hissing hot with something like approval, hung up the coat, uttering no unfavourable comment, no rhetorical 'Where's the money going to come from to buy new epaulettes when all the bullion's wore off, in consequence of being flung down regardless?' but carried on with the conversation that Jack's departure had interrupted. 'You did say, sir, as how they had no teeth?'

'Not a sign of them, Killick. Not a sign, before I sailed.'

'Well, I'm right glad on it'—producing a handkerchief with two massive pieces of coral in its folds—'because this will help to cut 'em, as they say.'

'Thank you, Killick. Thank you kindly. Splendid pieces, upon my word: they shall go home in the first ship.'

'Ah, sir,' said Killick, sighing through the stern-window, 'do you remember that wicked little old copper in the back-kitchen, and how we roused out its flue, turning as black as chimney-sweeps?'

'That wicked little old copper will be a thing of the past, when next we see the cottage,' said Jack. 'The Hébé looked after that. And there will be a decent draught in the parlour, too, if Goadby knows his business.'

'And them cabbages, sir,' went on Killick, in an ecstasy of nostalgia. 'When I last see 'em, they had but four leaves apiece.'

'Jack, Jack,' cried Stephen, running in. 'I have been sadly remiss. You are promoted, I find. You are a great man—you are virtually an admiral! Give you joy, my dear, with all my heart. The young man in black clothes tells me you are the greatest man on the station, after the Commander-in chief.'

'Why, I am commodore, as most people have the candour to admit,' said Jack. 'But I did mention it before, if you recollect. I spoke of my pennant.'

'So you did, joy; but perhaps I did not fully apprehend its true significance. I had a cloudy notion that the word 'commodore' and indeed that curious little flag were connected with a ship rather than with a man—am almost sure that we called the most important ship in the East India fleet, the ship commanded by the excellent Mr Muffit, the commodore. Pray explain this new and splendid rank of yours.'

'Stephen, if I tell you, will you attend?'

'Yes, sir.'

'I have told you a great deal about the Navy before this, and you have not attended. Only yesterday I heard you give Farquhar a very whimsical account of the difference between the halfdeck and the quarterdeck, and to this day I do not believe you know the odds between . . .' At this point he was interrupted by the black-coated Mr Peter with a sheaf of papers, by a messenger from the general at Cape Town, and by Seymour, with whom he worked out a careful list of those men who could be discharged into the Néréide either in the light of their own crimes or in that of the frigate's more urgent needs, and lastly by the Commander-in-chief's secretary, who wished to know whether his cousin Peter suited, to say that Admiral Bertie, now much recovered, sent his compliments: without wishing to hurry the Commodore in any way, the Admiral would be overjoyed to hear that he had put to sea.

'Well, now, Stephen,' said Jack at last, 'this commodore lark: in the first place I am not promoted at all—it is not a rank but a post, and J. Aubrey does not shift from his place on the captains' list by so much as the hundredth part of an inch. I hold this post just for the time being, and when the time being is over, if you follow me, I go back to being a captain again. But while it lasts I am as who should say an acting temporary unpaid rear admiral; and I command the squadron.'

'That must warm your heart,' said Stephen. 'I have often known you chafe, in a subordinate position.'

'It does: the word is like a trumpet. Yet at the same time . . . I should not say this to anyone but you, Stephen, but it is only when you have an enterprise of this kind on your hands, an enterprise where you have to depend on others, that you understand what command amounts to.'

'By others you mean the other commanders, I take it? Sure, they are an essential factor that must be thoroughly understood. Pray o

pen your mind upon them, without reserve.' Jack and Stephen had sailed together in many ships, but they had never discussed the officers: Stephen Maturin, as surgeon, had messed with them, and although he was the captain's friend he belonged to the gun-room: the subject was never, never raised. Now the case altered: now Stephen was Jack's political colleague and adviser; nor was he bound in any way to the other commanding officers. 'Let us begin with the Admiral; and Jack, since we are to work openly together, we must speak openly: I know your scruples and I honour them, yet believe me, brother, this is no time for scruples. Tell, do you look for full, unreserved support from Mr Bertie?'

'He is a jolly old boy,' said Jack, 'and he has been as kind and obliging to me as I could wish: he confirmed my acting-order for Johnson at once—a most handsome compliment. As long as all goes well, I make no doubt he will back us to the hilt; apart from anything else, it is entirely in his interest. But his reputation in the service—well, in Jamaica they called him Sir Giles Overreach, from the fellow in the play, you know; and he certainly overreached poor James. A good officer, mark you, though he don't see much farther through a brick wall than another man.' He considered for a while before saying, 'But if I made a mistake, I should not be surprised to be superseded: nor if I stood between him and a plum. Though as things stand, I cannot see how that could come about.'

'You have no very high opinion of his head, nor of his heart.'

'I should not go as far as that. We have different ideas of what is good order in a ship, of course . . . no, I shall tell you one thing that makes me uneasy about his sense of what is right. This Russian brig. She is an embarrassment to everybody. The Admiral wishes her away, but he will not take the responsibility of letting her go. He will not accept the responsibility of making her people prisoners, either—among other things they would have to be fed, with everything charged against him if Government disapproved. So what he has done is to make the captain give his word not to escape and has left him lying there, ready for sea: he is trying to starve Golovnin out by allowing no rations for his men. Golovnin has no money and the merchants will not accept bills drawn on Petersburg. The idea is that he will break his word and disappear some dirty night when the wind is in the north-west. His word means nothing to a foreigner, said the Admiral, laughing; he wondered Golovnin had not gone off six months ago—he longed to be rid of him. He took it so much as a matter of course—did not hesitate to tell it—thought it such a clever way of covering himself—that it made my heart sink.'

Stephen said, 'I have noticed that some old men lose their sense of honour, and will cheerfully avow the strangest acts. What else affects your spirits, now? Corbett, I dare say? In that case the beadle within has quite eaten up the man.'

'Yes: he is a slave-driver. I do not say a word against his courage, mark you; he has proved that again and again. But by my book his ship is in very bad order indeed. She is old too, and only a twelve-pounder. Yet with the odds as they are, I cannot possibly do without her.'

'What do you say to the captain of the Sirius?'

'Pym?' Jack's face brightened. 'Oh, how I wish I had three more Pyms in three more Siriuses! He may be no phoenix, but he is the kind of man I like—three Pyms, and there would be your band of brothers for you. I should have to do myself no violence, keeping on terms with three Pyms. Or three Eliots for that matter: though he will not be with us long, more's the pity. He means to invalid as soon as ever he can. As it is, I shall have to humour Corbett to some degree, and Clonfert; for without there is a good understanding in a squadron, it might as well stay in port. How I shall manage it with Clonfert I can hardly tell: I must not get athwart his hawse if I can avoid it, but with that damned business of his wife I am half way there already. He resented it extremely—refused my invitation, which is almost unheard-of in the service, previous engagement or not: and there was no previous engagement. This is an odd case, Stephen. When we talked about him some time ago, I did not like to say I had my doubts about his conduct—an ugly thing to say about any man. But I had, and I was not the only one. Yet maybe I was not as wise as I supposed, for although he still looks like a flash cove in a flash ship, he did distinguish himself up the Mediterranean with Admiral Smith.'

'That, I presume, was where he came by his star? It is an order I have never seen.'

'Yes, the Turks handed out quite a number, but they were thought rather absurd, and not many officers asked permission to wear them: only Smith and Clonfert, I believe. And he has also carried out some creditable raids and cutting-out expeditions in these waters. He knows them well, and he has a native pilot; the Otter draws little water, even less than the Néréide, so he can stand in among the reefs; and according to Admiral Bertie he might almost be setting up as a rival to Cochrane in the matter of distressing the enemy.'

'Yes: I have heard of his enterprise, and of his ship's ability to go close to the shore. I shall no doubt have to be with him from time to time, to be landed and taken off. But just now you spoke of the odds. How do you see them at present?'

'Simply in terms of ships and guns, and only from the point of view of fighting at sea, they are rather against us. Then if you allow for the fact that we shall be more than two thousand miles from our base while they are in their home waters, with supplies at hand, why, you might say that they are in the nature of three to five. In the Channel or the Mediterranean I should put it nearer evens, since we are at sea all the time in those parts, and they are not: but their heavy frigates have been out the best part of a year now, plenty of time to work up their crews, given competent officers; and upon the whole the French officers are a competent set of men. But all this is very much up in the air—there are so many unknowns in the equation. For one thing, I know nothing of their captains, and everything depends on them. Once I catch sight of them at sea I shall be able to reckon the odds more accurately.'

'Once you have had a brush with them, you mean?'

'No. Once I have seen them, even hull down on the horizon.'

'Could you indeed judge of their abilities at so remote a view?'

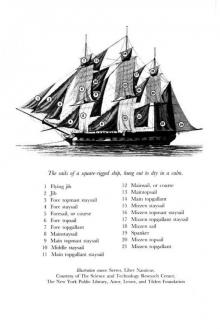

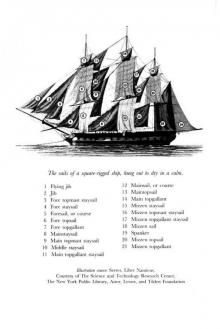

'Of course,' said Jack a little impatiently. 'What a fellow you are, Stephen. Any sailor can tell a great deal from the way another sailor sets his jib, or goes about, or flashes out his stuns'ls, just as you could tell a great deal about a doctor from the way he whipped off a leg.'

'Always this whipping off of a leg. It is my belief that for you people the whole noble art of medicine is summed up in the whipping off of a leg. I met a man yesterday—and he was so polite as to call on me today, quite sober—who would soon put you into a better way of thinking. He is the Otter's surgeon. I should probably have to cultivate his acquaintance in any event, for our own purposes, since the Otter is, as you would say, an inshore prig; but I do not regret it now that I have met him. He is, or was, a man of shining parts. But to return to our odds: you would set them at five to three in favour of the French?'

'Something of that kind. If you add up guns and crews and tonnage it is a great deal worse; but of course I cannot really speak to the probability until I see them. Yet although I have sent a hundred Boadiceas to lend a hand aboard the Sirius, and although I know Pym is doing his utmost to get her ready for sea, our own ship has to take in six months' stores, and I should love to careen her too, the last chance of a clean bottom for God knows how long—I cannot see how we can sail before Saturday's tide. I shall keep the people hard at it, and harry the arsenal until they wish me damned, but apart from that there is nothing I can do: there is nothing that the Archangel Gabriel could do. So what do you say to some music, Stephen? We might work out some variations on "Begone Dull Care".'

Chapter Four

The squadron, standing north-east with the urgent tradewind on the beam, made a noble sight; their perfect line covered half a mile of sea—and such a sea: the Indian Ocean at its finest, a sapphire not too deep, a blue that turned their worn sails a dazzling white. Sirius, Néréide, Raisonable, Boadicea, Otter, and away to leeward the East India

Company's fast-sailing armed schooner Wasp, while beyond the Wasp, so exactly placed that it outlined her triangular courses, floated the only bank of cloud in the sky, the flat bottomed clouds hanging over the mountains of La Réunion, themselves beneath the horizon.

The Cape and its uneasy storms lay two thousand miles astern, south and westward, eighteen days' sweet sailing; and by now the crews had long since recovered from the extreme exertion of getting their ships ready for sea three tides before it seemed humanly possible. But once at sea new exertions awaited them: for one thing, the perfection of this line, with each ship keeping station on the pennant at exactly a cable's length, could be achieved only by incessant care and watchfulness. The Sirius, with her foul bottom, kept setting and taking in her topgallants; the Néréide had perpetually to struggle against her tendency to sag to leeward; and Jack, standing on the poop of the Raisonable, saw that his dear but somewhat sluggish Boadicea was having an anxious time of it—Eliot was fiddling with his royals—while only the pennant-ship, fast in spite of her antiquity, and the Otter were at ease. And for another, all the ships except the Boadicea were disturbed, upset and harassed by the Commodore's passion for gunnery.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea