- Home

- Patrick O'Brian

The Wine-Dark Sea Page 10

The Wine-Dark Sea Read online

Page 10

'I am so sorry, sir,' said Martin. 'I broke one when I was mixing the draughts, and I forgot to tell Padeen.'

Both Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin were much attached to their wives, and both wrote to them at quite frequent intervals; but whereas Jack's letters owed their whole existence to the hope that they would reach home by some means or another—merchantman, man-of-war or packet—or failing that that they would travel there in his own sea-chest and be read aloud to Sophie with explanations of just how the wind lay or the current set, Stephen's were not always intended to be sent at all. Sometimes he wrote them in order to be in some kind of contact with Diana, however remote and one-sided; sometimes to clarify things in his own mind; sometimes for the relief (and pleasure) of saying things that he could say to no one else, and these of course had but an ephemeral life.

'My dearest soul,' he wrote, 'when the last element of a problem, code or puzzle falls into place the solution is sometimes so obvious that one claps one's hand to one's forehead crying, "Fool, not to have seen that before." For some considerable time now, as you would know very well if we had some power of instant communication, I have been concerned about the change in my relations with Nathaniel Martin, by the change in him, and by his unhappiness. Many and sound reasons did I adduce when last I wrote, naming an undue concern with money and a conviction that its possession should in common justice win him more consideration and happiness than he possesses, as well as many other causes such as jealousy, the boredom of uncongenial companions from whom there is no escape, a longing for home, wife, relations, consequence, peace and quiet, and a fundamental unsuitability for naval life, prolonged naval life. But I did not mention the efficient cause because I did not perceive it until today, though it should have been evident enough from his intense application to Astruc, Booerhaave, Lind, Hunter and what few other authorities on the venereal distemper we possess (we lack both Locker and van Swieten), and even more from his curiously persistent eager detailed enquiries about the possibility of infection from using the same seat of ease, drinking from the same cup, kissing, toying and the like. Whether he has the disease I cannot tell for sure without a proper examination, though I doubt he has it physically: metaphysically however he is in a very bad way. Whether he lay with her or not in fact he certainly wished to do so and he is clerk enough to know that the wish is the sin; and being also persuaded that he is diseased he looks upon himself with horror, unclean without and within. Unhappily he has taken yesterday's disagreement more seriously than I did—our relations are a cool civility at the best—and in these circumstances he will not consult me. Nor obviously can I obtrude my services. Self-hatred usually seems more likely to generate hatred of others (or at least surliness and a sense of grievance) than mansuetude. Poor fellow, he is invited to dine in the cabin this afternoon, and to bring his viola. I dread some kind of éclat: he is in a very nervous state.'

There was a confident knock on the door and Mr Reade walked smiling in, quite sure of his welcome. From time to time what was left of his arm needed dressing, and this was one of the appointed days: Stephen had forgotten it; Padeen had not, and the bandage stood on the aftermost locker. While it was putting on, fold after exactly-spaced fold, Reade said, 'Oh sir, I had a wonderful thought in the graveyard watch. Please would you do me a great kindness?'

'I might,' said Stephen.

'I was thinking about going to Somerset House to pass for lieutenant when we get home.'

'But you are not nearly old enough, my dear.'

'No, sir: but you can always add a year or two: the examining captains only put "appears to be nineteen years of age", you know. Besides, I shall be nineteen in time, of course, particularly if we go on at this pace; and I have my proper certificates of sea-time served. No. The thing that worried me was that since I am now only a tripod rather than a quadrupod, they might be doubtful about passing me. So I have to have everything on my side. These calm days I have been copying out my journals fair—you have to show them up, you know—and in the night it suddenly occurred to me that it would be a brilliant stroke and amaze the captains, was I to add some seamanlike details in French.'

'Sure it could not fail to do so.'

'So I thought if I took Colin, one of the Franklins in my division, a decent fellow and prime seaman though he has scarcely a word of English, on to the forecastle in the first dog, shall we say, sir, and pointed to everything belonging to the foremast and he told me the French and you told me how to write it down, that would be very capital. It would knock the captains flat—such zeal! But I am afraid I am asking for too much of your time, sir.'

'Not at all. Hold this end of the bandage, will you, now? There: belay and heave off handsomely.'

'Thank you very much indeed, sir. I am infinitely obliged. Until the first dog, then?'

'Never you think so, Mr Reade, sir,' said Killick, coming in with Stephen's new-brushed good blue coat and white kerseymere breeches over his arm. 'Not the first dog, no, nor yet the last. Which the Doctor is going to dine with the Captain, and they won't be done in the melodious line before the setting of the watch. Now, sir, if you please,'—to Stephen—'let me have that wicked old shirt and put this one on, straight from the smoothing-iron. There is not a moment to be lost.'

In fact the dinner went off remarkably well. Martin might not carry Jack Aubrey in his heart, but he respected him as a naval commander and as a patron: it would be ungenerous to say that his respect was increased by the prospect of another benefice to come, but at some level the fact may well have had its influence. At all events, in spite of looking drawn and unwell he played his part as a cheerful, appreciative guest quite well, except that he drank almost no wine; and he told two anecdotes of his own initiative: one of a trout that he tickled as a boy under the fall of a weir, and one of an aunt who had a cat, a valuable cat that lived with her in a house near the Pool of London—the animal vanished—enquiries in every direction—tears that lasted a year, indeed until the day the cat walked in, leapt on to its accustomed chair by the fire and began to wash. Curiosity had led it aboard a ship bound for Surinam, a ship from the Pool that had just returned.

After dinner it was proposed that they should play, and since one of the chief purposes of the feast was to give Tom Pullings pleasure they played tunes he knew very well. Songs, as often as not, and dances, some delightful melodies with variations on them; and from time to time Jack and Pullings sang.

'Your viola has profited immensely from its repair,' said Jack when they were standing up for leave-taking. 'It has a charming tone.'

'Thank you, sir,' said Martin. 'Mr Dutourd has improved my fingering, tuning and bowing—he knows a great deal about music—he loves to play.'

'Ah, indeed?' said Jack. 'Now, Tom, do not forget your horizon-glass, I beg.'

In his role of virtually omnipotent captain Jack could be deaf to a hint, particularly if it reached him indirectly: Stephen was less well placed, and two days later when Dutourd, having wished him a good morning and having spoken of the pleasure it had given him to linger on the quarterdeck all the time they played, went on to say, with an ease that surprised Maturin until he recalled that wealthy men were used to having their wishes regarded, 'It would perhaps be too presumptuous in me to entreat you to let Captain Aubrey know that it would give me even greater pleasure to be admitted to one of your sessions: I am no virtuoso, but I have held my own in quite distinguished company; and if I were allowed to play second fiddle we might embark upon quartets, which have always seemed to me the quintessence of music.'

'I will mention it if you wish,' said Stephen, 'but I should observe that in general the Captain looks upon these as little private affairs, quite unbuttoned and informal.'

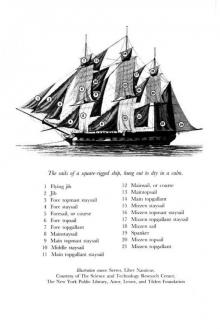

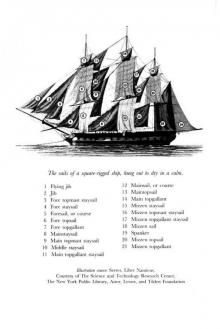

'Then perhaps I must be content to listen from afar,' said Dutourd, taking no apparent offence. 'Yet it would be benevolent in you to speak of it, if a suitable occasion should offer.' He broke off to ask what was going on aboard the Franklin. Stephen told him that they were rigging out the for

etopgallant studdingsail booms. 'Les bouts-dehors des bonnettes du petit perroquet,' he added, seeing Dutourd's look of blank ignorance, an ignorance equal to his own until yesterday, when he had helped Reade to write the terms in his journal. From this they moved on to a consideration of sails in general; and after a while, when Stephen was already impatient to be gone, Dutourd, looking him full in the face, said, 'It is surely very remarkable that you should know the French for studdingsail booms as well as for so many animals and birds. But it is true that you have a remarkable command of our language.' A meditative pause. 'And now that I have the honour of being better acquainted with you it seems to me that we may have met before. Do not you know Georges Cuvier?'

'I have been introduced to Monsieur Cuvier.'

'Yes. And were you not at Madame Roland's soirées from time to time?'

'You are probably thinking of my cousin Domanova. We are often confused.'

'Perhaps so. But tell me, sir, how do you come to have a cousin called Domanova?'

Stephen looked at him with astonishment, and Dutourd, visibly drawing himself in, said, 'Forgive me, sir: I am impertinent.'

'Not at all, sir,' replied Stephen, walking off. His inward voice ran on, 'Is it possible that the animal has recognized me—that he has some notion however vague of what we are about—and that this is in some degree a threat?' Dutourd's was not an easy face to read. Superficially it had the open simplicity of an enthusiast, together with the politeness of his class and nation; these did not of course exclude everyday cunning and duplicity, but there was also something else, a slight insistence in his look, a certain self-confidence, that might mean far deeper implications. 'Shall I never learn to keep my mouth shut?' he muttered, opening the sick-berth door, and aloud, 'God and Mary and Patrick be with you,' in answer to Padeen's greeting. 'Mr Martin, a good morning to you.'

'How these halcyon days go on and on, the one following the other with only a perfect night between,' he said, walking into the cabin. 'We might almost be on dry land. But tell me, Jack, will it never rain at all—hush. I interrupt your calculations, I find.'

'What is twelve sixes?' asked Jack.

'Seventy-two,' said Stephen. 'My shirt is like a cilice with the salt. I should wear it dirty and reasonably soft, but that Killick takes it away—he finds it out with a devilish ingenuity and flings it into the sea-water tub and I am convinced that he adds more salt from the brine-tubs.'

'What is a cilice?'

'It is a penitential garment made of the harshest cloth known to man and worn next the skin by saints, hermits, and the more anxious sinners.'

Jack returned to his figures and Stephen to his disagreeable reflexions. 'What goeth before destruction?' he asked. 'Pride goeth before destruction, that is what. I was so proud of knowing those spars in English, let alone in French, that I could not contain, but must be blabbing like a fool. Hair-shirt, indeed: the Dear knows I deserve one.'

In time Jack put down his pen and said, 'As for rain, there is no hope of it, according to the glass. But I have been casting the prize accounts, as far as I can without figures for the Franklin's specie: a roundish figure, which is some sort of consolation.'

'Very good. To predatory creatures like myself there is something wonderfully fetching about a prize. The very word evokes a smile of concupiscent greed. Speaking of the Franklin reminds me that Dutourd wishes you to know that he would be glad of an invitation to play music with us.'

'So I gather from Martin,' said Jack, 'and I thought it a most uncommon stroke of effrontery. A fellow with wild, bloody, regicide revolutionary ideas, like Tom Paine and Charles Fox and all those wicked fellows at Brooks's and that adulterous cove—I forget his name, but you know who I mean—'

'I do not believe I am acquainted with any adulterers, Jack.'

'Well, never mind. A fellow who roams about the sea attacking our merchantmen with no commission or letter of marque from anyone, next door to a pirate if not actually bound for Execution Dock—be damned if I should invite him if he were a second Tartini, which he ain't—and in any case I disliked him from the start—disliked everything I heard of him. Enthusiasm, democracy, universal benevolence—a pretty state of affairs.'

'He has qualities.'

'Oh yes. He is not shy; and he stood up very well for his own people.'

'Some of ours think highly of him and his ideas.'

'I know they do: we have some hands from Shelmerston, decent men and prime seamen, who are little better than democrats—republicans, if you follow me—and would easily be led astray by a clever political cove with a fine flow of words: but the man-of-war's men, particularly the old Surprises, do not like him. They call him Monsieur Turd, and they will not be won round by smirking and leering and the brotherhood of man: they dislike his notions as much as I do.'

'They are tolerably chimerical, admittedly, and it is surprising that a man of his age and his parts should still entertain them. In 1789 I too had great hopes of my fellows, but now I believe the only point on which Dutourd and I are in agreement is slavery.'

'Well, as for slavery . . . it is true that I should not like to be one myself, yet Nelson was in favour of it and he said that the country's shipping would be ruined if the trade were put down. Perhaps it comes more natural if you are black . . . but come, I remember how you tore that unfortunate scrub Bosville to pieces years ago in Barbados for saying that the slaves liked it—that it was in their masters' interest to treat them kindly—that doing away with slavery would be shutting the gates of mercy on the negroes. Hey, hey! The strongest language I have ever heard you use. I wonder he did not ask for satisfaction.'

'I think I feel more strongly about slavery than anything else, even that vile Buonaparte who is in any case one aspect of it . . . Bosville . . . the sanctimonious hypocrite . . . the silly blackguard with his "gates of mercy", his soul to the Devil—a mercy that includes chains and whips and branding with a hot iron. Satisfaction. I should have given it him with the utmost good will: two ounces of lead or a span of sharp steel; though common ratsbane would have been more appropriate.'

'Why, Stephen, you are in quite a passion.'

'So I am. It is a retrospective passion, sure, but I feel it still. Thinking of that ill-looking flabby ornamented conceited self-complacent ignorant shallow mean-spirited cowardly young shite with absolute power over fifteen hundred blacks makes me fairly tremble even now—it moves me to grossness. I should have kicked him if ladies had not been present.'

'Come in,' called Jack.

'Mr Grainger's duty, sir,' said Norton, 'and the wind is hauling aft. May he set the weather studdingsails?'

'Certainly, Mr Norton, as soon as they will stand. I shall come on deck the moment I have finished these accounts. If the French gentleman is at hand, pray tell him I should like to see him in ten minutes. Compliments, of course.'

'Aye aye, sir. Studdingsails as soon as they will stand. Captain's compliments to Monsieur Turd . . .'

'Dutourd, Mr Norton.'

'Beg pardon, sir. To Monsieur Dutourd and wishes to see him in ten minutes.'

On receiving this message Dutourd thanked the midshipman, looked at Martin with a smile, and began walking up and down from the taffrail to the leeward bow-chaser and back again, looking at his watch at each turn.

'Come in,' cried Jack Aubrey yet again. 'Come in, Monsieur—Mr Dutourd, and sit down. I am casting my prize-money accounts and should be obliged for a statement of the amount of specie, bills of exchange and the like carried in the Franklin: I must also know, of course, where it is kept.'

Dutourd's expression changed to an extraordinary degree, not merely from confident pleasurable anticipation to its opposite but from lively intelligence to a pale stupidity.

Jack went on, 'The money taken from your prizes will be returned to its former owners—I already have sworn statements from the ransomers—and the Franklin's remaining treasure will be shared out among her captors, according to the laws of the sea. Your private purse, li

ke your private property, will be left to you; but its amount is to be written down.' Dutourd's wits had returned to him by now. Jack Aubrey's massive confidence told him that any sort of protest would be worse than useless: indeed, this treatment compared most favourably with the Franklin's, whose prisoners were stripped bare; but the long pause between capture and destitution, so very unlike the instant looting he had seen before, had bred illogical hopes. He managed a look of unconcern, however, and said, 'Vae victis' and produced two keys from an inner pocket. 'I hope you may not find that my former shipmates have been there before you,' he added. 'There were some grasping fellows among them.'

There were some grasping fellows aboard the Surprise too, if men who dearly loved to get their hands upon immediate ringing gold and silver rather than amiable but mute, remote, almost theoretical pieces of paper, are to be called grasping. There had been the sound of chuckling throughout the ship ever since Oracle Killick let it be known 'that the skipper had got round to it at last', and a boat carrying Mr Reade, Mr Adams and Mr Dutourd's servant had pulled across to the Franklin, returning with a heavy chest that came aboard not indeed to cheers, for that would not have been manners, but with great cheerfulness, good will, and anxious care while it hung in the void, and witticisms as it swung inboard, to be lowered as handsomely as a thousand of eggs.

Even until the next day, however, Stephen Maturin remained unaware of all this, for not only had he dined by himself in the cabin, Jack Aubrey being aboard the Franklin, but his mind was almost entirely taken up with cephalopods; and as far as he took notice of the gaiety at all (by no means uncommon in the Surprise, that happy ship) he attributed it to the freshening of the breeze, which was now sending the two ships along at close on five knots with promise of better to come. He had had to make his morning rounds alone, Martin having remained in bed with what he described as a sick headache; Jack's breakfast and Stephen's had for once failed to coincide, and they had exchanged no more than a wave from the sea to the deck before Stephen sat down to his collection. Some of the cephalopods were dried, some were in spirits, one was fresh: having ranged the preserved specimens in due order and checked the labels and above all the spirit level (a necessary precaution at sea, where he had known jars drained dry, even those containing asps and scorpions) he turned to the most interesting and most recent creature, a decapod that had fixed the terrible hooks and suckers of its long arms into the net of salt beef towing over the side to get rid of at least some of the salt before the pieces went into the steep-tub—had fixed them with such obstinate strength that it had been drawn aboard.

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Rendezvous and Other Stories

The Rendezvous and Other Stories Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard

Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard The Hundred Days

The Hundred Days The Yellow Admiral

The Yellow Admiral The Fortune of War

The Fortune of War The Mauritius Command

The Mauritius Command Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure

Beasts Royal: Twelve Tales of Adventure A Book of Voyages

A Book of Voyages The Surgeon's Mate

The Surgeon's Mate The Golden Ocean

The Golden Ocean Hussein: An Entertainment

Hussein: An Entertainment H.M.S. Surprise

H.M.S. Surprise The Far Side of the World

The Far Side of the World Blue at the Mizzen

Blue at the Mizzen The Unknown Shore

The Unknown Shore The Reverse of the Medal

The Reverse of the Medal Testimonies

Testimonies Master and Commander

Master and Commander The Letter of Marque

The Letter of Marque Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour The Nutmeg of Consolation

The Nutmeg of Consolation 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey The Thirteen-Gun Salute

The Thirteen-Gun Salute The Ionian Mission

The Ionian Mission Men-of-War

Men-of-War The Commodore

The Commodore The Catalans

The Catalans Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission

Aub-Mat 08 - The Ionian Mission Post Captain

Post Captain The Road to Samarcand

The Road to Samarcand Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen

Book 20 - Blue At The Mizzen Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation

Book 14 - The Nutmeg Of Consolation Caesar

Caesar The Wine-Dark Sea

The Wine-Dark Sea Book 8 - The Ionian Mission

Book 8 - The Ionian Mission Book 12 - The Letter of Marque

Book 12 - The Letter of Marque Hussein

Hussein Book 9 - Treason's Harbour

Book 9 - Treason's Harbour Book 19 - The Hundred Days

Book 19 - The Hundred Days Master & Commander a-1

Master & Commander a-1 Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal

Book 11 - The Reverse Of The Medal Book 2 - Post Captain

Book 2 - Post Captain The Truelove

The Truelove The Thirteen Gun Salute

The Thirteen Gun Salute Book 17 - The Commodore

Book 17 - The Commodore The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey

The Final, Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World

Book 10 - The Far Side Of The World Book 5 - Desolation Island

Book 5 - Desolation Island Beasts Royal

Beasts Royal Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral

Book 18 - The Yellow Admiral Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes

Book 15 - Clarissa Oakes Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate

Book 7 - The Surgeon's Mate Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise

Book 3 - H.M.S. Surprise Desolation island

Desolation island Picasso: A Biography

Picasso: A Biography Book 4 - The Mauritius Command

Book 4 - The Mauritius Command Book 1 - Master & Commander

Book 1 - Master & Commander Book 6 - The Fortune Of War

Book 6 - The Fortune Of War Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute

Book 13 - The Thirteen-Gun Salute Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea

Book 16 - The Wine-Dark Sea